Why this teacher wants to decolonise the university

If a university doesn’t take a stand, who will? Ginie Servant appeals for a re-evaluation of engagement on campus. To start with, she wants to ‘decolonise’ academic education.

Image by: Geertje van Achterberg

Read part 1 in the series Education Pioneers

-

‘We aren’t around to make students smarter, but more critical’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

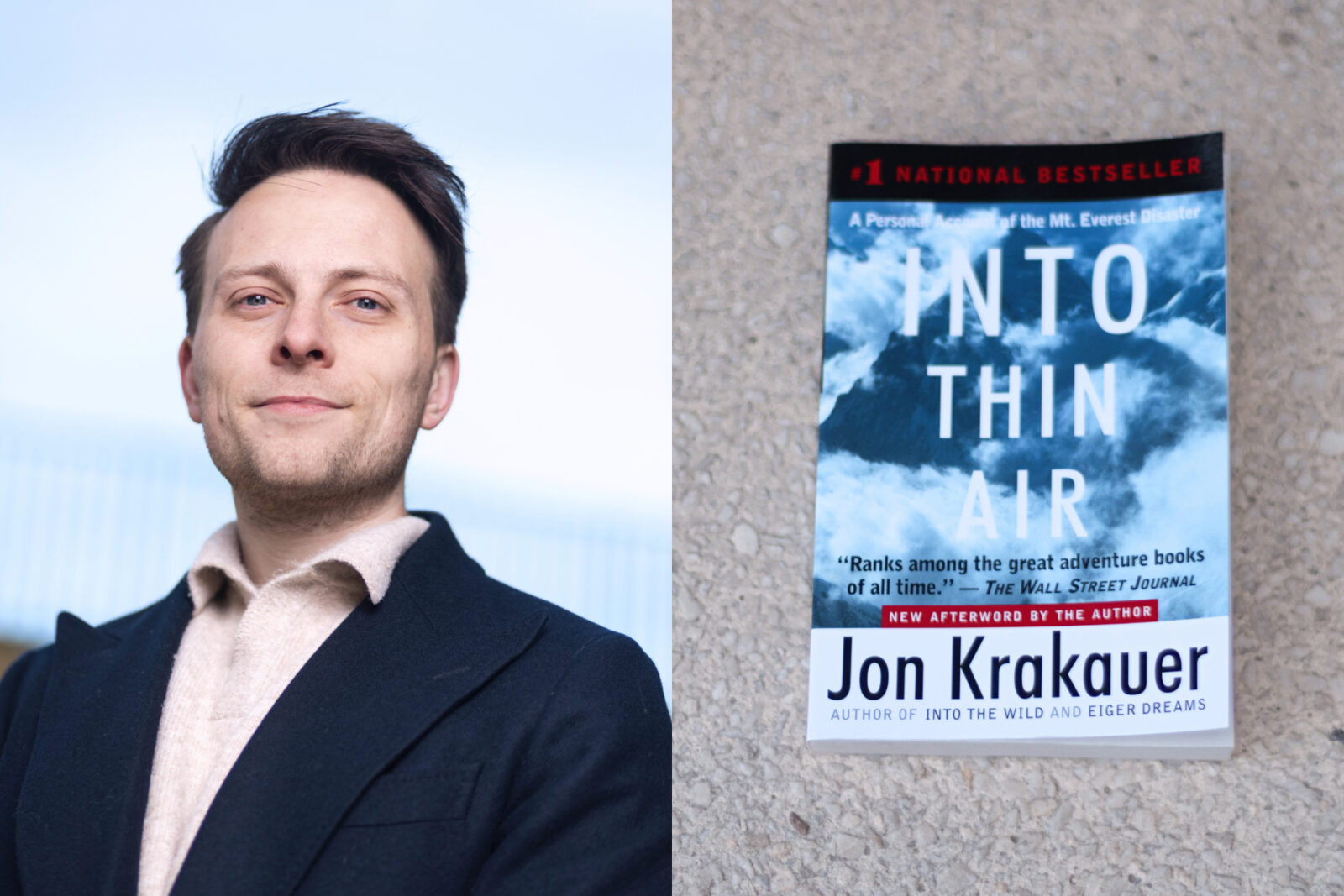

A few weeks after the Grenfell Tower fire in London, which cost the lives of 71 people, Ginie Servant discussed the tragedy in a lecture. It was about globalisation and inequality. She could have brought loads of theory for her students. Instead, the University College lecturer brought a photo of the burnt-out carcass of the social housing towers and said: this is what happens when a city takes away from the original residents and gives to investors and expats.

Servant is blunt. “As academics, we like to pretend that we’re in an ivory tower,” she says. Universities – in the 1960s and 70s still the cradle of engagement and criticism of the system – have become cowardly. “As if we play no role in such developments. But if you travel a lot and talk to locals, you realise that people are suffering under the systems that we reproduce. I often hear it said: science is neutral. But, neutrality is nothing more than accepting the status quo.” She feels it is her task and that of her colleagues to look for alternatives together with students. “Otherwise, as an academic you’re saying: I’m satisfied with the world as it is now – including inequality, war, suffering.”

Ginie Servant is a senior lecturer at Erasmus University College and postdoc researcher associated with Aalborg University. She developed the twoday ‘decolonisation workshop’ Teaching in the International Classroom and is co-founder of Fair Fight. She obtained her PhD cum laude on a historic study into problem-based learning.

Militant

Image by: Geertje van Achterberg

‘I want to show that, as white Westerners, we aren’t always right’

Servant sits on the sofa opposite me, slightly hunched forward, elbows on her knees, on the top floor of the beautifully renovated former Education Museum that has been home to the Erasmus University College for the past few years. The Frenchwoman looks fierce and militant. For decades, universities have contributed to existing power differences rather than confronting them, she says. She appeals for a return to engagement in the lecture hall. The first step is to look for one’s own bias. She calls this ‘decolonisation of the university’.

“I want to show that, as white Westerners, we aren’t always right. That internationalisation is not the same as Americanisation. That we consistently look down on partners from Asia, Latin America and Africa. And that in the Western world, we are so attached to our privileges that it’s almost impossible to recognise it, let alone change anything.”

She developed a two-day decolonisation training for lecturers, which can be used in any faculty (so far only 24 lecturers have done it). One of the things she asks participants to do is to bring along the compulsory reading list for their subject and then to cross off British and American authors. After which – she smiles – there often aren’t many left. “Then I ask them: have you ever tried to look at this problem in another way? Often this generates a serious protest: there is no other view, all the relevant literature comes from the Anglo-Saxon world. To which I reply: you’ve got fifteen minutes to find an alternative.” Again that smile: “They always manage to find an African or Asian school of thought that they hadn’t previously seen.”

Poor black orphans

Read part 2 in the series

-

‘It’s time for new rules in education’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

You won’t find anyone much more international than Servant. Born in the woods near Chantilly (an hour north of Paris), she partly grew up in the Netherlands. Mother worked in education, father was an Apple engineer. She went to an international school in Hilversum and studied International Relations (MA) and International Law (MA) in Kent.

In the Catholic environment in which she grew up, it was normal to care about people who were less fortunate than you were. It was only later that she realised that people regarded development in a ‘very colonial manner’. “So in the sense of: we’re going to help those poor black orphans in Africa. Let’s set up a mission.”

During a brief spell working for an NGO in Vietnam after graduating in 2008 – ‘it was crisis, so I took anything’ – she experienced for herself ‘the dark side of the I-want-to-save-the-world mentality’. With a knowing glance: “That we Westerners are coming to tell you how to do things differently. That went totally wrong.”

A career in research followed more or less by chance, after a job as research assistant in Singapore. Through friends of friends, she met Henk Schmidt (former rector magnificus at Erasmus University and spiritual father of the EUC). Under his mentorship, she eventually got her PhD cum laude with a thesis about the history of problem-based learning (PBL), for which she travelled halfway around the world.

Liberate

‘Everyone tries to keep the conflict out of the university’

“My vision for education is largely based on critical pedagogy,” Servant explains. “That movement, which originated in the 1960s, had great difficulty with the fact that higher education was an elite system, that produced new elites. Thet believed – in a very neo-Marxist way – that education could serve to elevate and liberate labourers, women, functional illiterates and other marginal groups in society.”

An important element of this is dialectics, she explains, the idea that it is useful to bring together two contrasting, confrontational perspectives and then create a synthesis. In this way, she introduces decolonisation to her students. Recently, for example, that generated a heated discussion about institutional racism in one of her lectures. Or in an economic course that she was giving: a serious confrontation between free-market adepts and socialists in the group. “Everyone tries to keep the conflict out of the university (for example with the appeal for ‘safe spaces’, red.). But such conflicts are actually very informative. As a teacher, I’m there to guide them through it.”

Furthermore, she feels that it’s her task to let things rip sometimes. When studying post-colonial relations as part of the International Relations Theory course, she asked students who had made their clothes. That went as follows:

Student: “Um, I don’t know, someone from China or somewhere?”

Servant: “No, I want you to find out exactly who it was.”

Student (with indignant voice): “I can’t possibly find out…”

Servant: “Why not?”

Student: “Whenever I buy something, I’d have to look back through the whole production chain.”

Servant, quasi-strict: “OK, fine. But then you’ve just internalised that it’s someone’s work, seven days a week, working very long hours, to make your clothes, which you’ve bought for very little money and which you throw away within two years.”

Student: “…”

Servant: “And that doesn’t bother you?”

Looking for conflict

Image by: Geertje van Achterberg

She totally believes in this confrontational way of working. In the basement of the university college, she once even set up a martial arts training (she loves karate). The aim was to train students and teachers to set aside the power differences between them and to seek conflict in a respectful way.

The problem is that didactically, you have to be well-qualified to guide students during this dialectic form of problem-based learning. And of course, small-scale problem-based learning is given by teachers who have only just graduated themselves. Because they’re cheap.

According to Servant, this illustrates the dilemma facing the university. “I wonder whether Erasmus University has a place for people who are serious about education. Young people filled with ambition arrive here and find themselves facing a wall of bureaucracy and organisational chaos the moment they want to do something that extends beyond their own faculty. We are currently losing a lot of good people because of the gaping hole between cheap PBL tutors and expensive researchers. We must regard teaching as a worthy profession, not as a ‘side project’ of researchers.”

That will cost a lot of money, she warns. “I feel it’s one of the great tragedies of our age that many of us consider education as a burden rather than as an investment in the future. I’ve done a lot of research into the reasons behind the success of Scandinavian countries. A hundred and fifty years ago, the situation was appalling there. How have they developed from being one of the last Western countries where people were still starving, into everyone’s model country where social provisions, democracy and welfare are concerned? The answer is: by investing in education.”

What type of left-wing activity is this?

Universities are left-wing strongholds, an opinion expressed increasingly frequently in recent years. Is this an example of that? “One of the best ways of dividing people is to pretend that there’s a binary contradiction between left and right,” says Servant. “You see that happening constantly at the moment. But are you left-wing if you take an activist approach to questioning the status quo? Then you assume that they are right-wing. The whole idea is that I’m not saying: we must all become communists or liberals. The great thing about a dialectic process is that, if you enter into discussion with each other, you find thousands of different perceptions of reality.”

De redactie

Latest news

-

Lydia celebrates thirty years of haircuts on campus: ‘She is the glue of our community’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Campus

-

-

Fewer and fewer top earners in higher education, most top salaries in Rotterdam

Gepubliceerd op:-

Campus

-

-

People sometimes make unpredictable choices, Dominic van Kleef knows

Gepubliceerd op:-

Page-turners

-

Comments

1 reactie

Comments are closed.

Read more in Education

-

Student with dyscalculia denied dispensation for statistics exams

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

-

First Philosophy: a philosophy podcast for beginners and advanced listeners

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

-

Adjusted internationalisation bill sent to Council of State

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Norvegicus op 26 April 2018 om 17:41

It’s unbelievable that we have activist trainers doing politics in the University by stealing tax-payer money, and have the guts to call it ‘education’.

Spreading lies and generalizations about what is going on in the planet to students instead of guiding them to find the sources they prefer and teach them to form their own opinion is shameful!

And what is this ‘decolonisation’ thing supposed to mean? This is our home, the cradle where Western culture lives and its fruits are seen in its magnificence and are available to all, not some invaded country. We are born free to embrace it or not, unlike what happens in places where your ‘critical’ and communist philosophies are dominant.