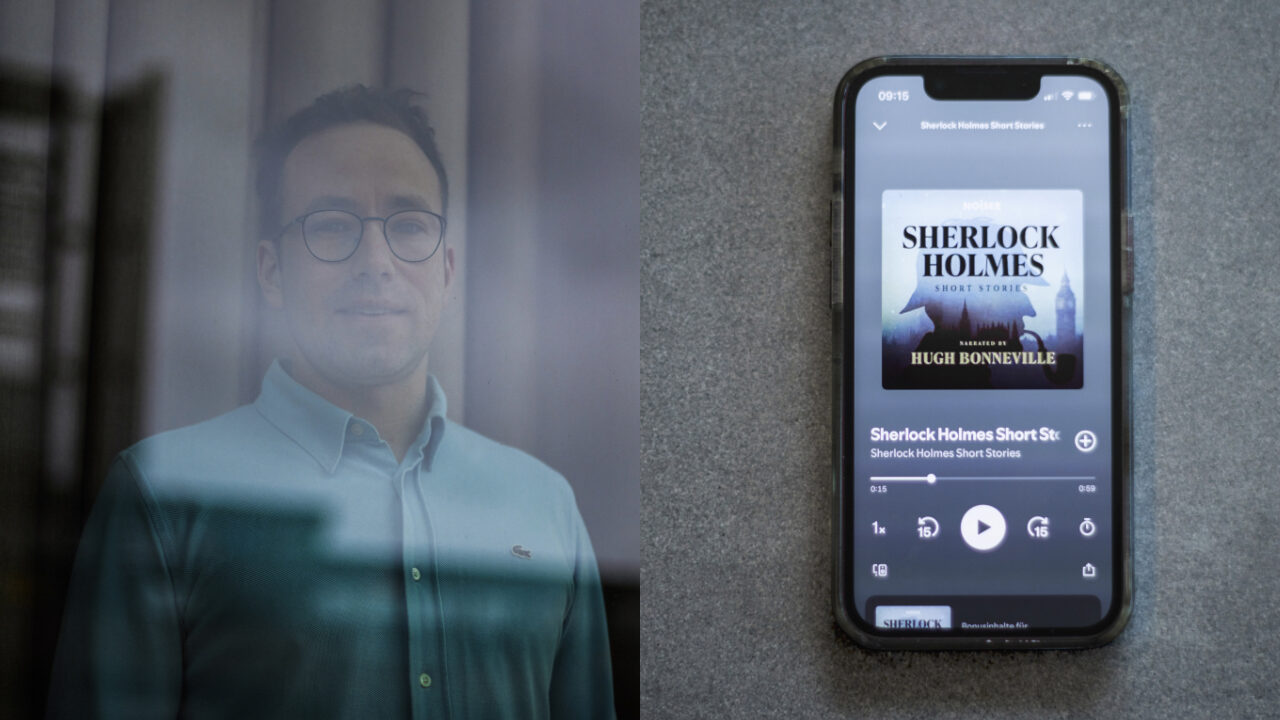

Sam van Leeuwen teaches Dutch to newcomers integrating into society

“Integration means learning the language”, says Sam van Leeuwen. As a Dutch language teacher for newcomers, he limits his lessons strictly to language. Complex subjects such as the colonial past, war or genocide, he reflects on through the books on his bedside table.

Image by: Leroy Verbeet

“What do you know about civic integration?”, asks Sam van Leeuwen at the start of the conversation. It could be a question from a quiz show like De Slimste Mens, but he means it rhetorically. “People think that inburgeren (civic integration, ed.) is about learning Dutch culture, or learning that you shouldn’t hit your wife, but that’s only one percent of it. Inburgeren means learning the language.”

And that also happens at the university. As a teacher of Dutch as a second language (NT2), Van Leeuwen teaches Dutch to young newcomers who aim to study at a Dutch university or university of applied sciences. He does this at the Language & Training Centre on campus. Elsewhere in the city, he teaches Dutch to people who no longer have such ambitions but still need to complete their inburgeren.

Sam van Leeuwen studied Criminology and Public Administration at EUR. He completed an internship at the Dutch embassy in Sri Lanka and worked as an English teacher in Colombia. In Rotterdam, he has taught Dutch at several schools. Since 2025, he has been working at the Language & Training Centre at EUR, where he teaches students following the education route – newcomers who wish to study in higher education after completing their inburgeren.

Living in another language

“Everything starts with language”, says Van Leeuwen about living in another country. But learning a new language in a country like the Netherlands is not easy. His students often complain that people on the street quickly switch to English: “And for many, Arabic is their mother tongue, which makes it tempting to communicate with each other in the language they feel most comfortable with.”

Van Leeuwen recognises this from his own time living in Colombia. After working for a consultancy firm, he left ‘out of a kind of escapism’ for South America to teach English. He had promised himself he would immerse fully in the Spanish-speaking culture, but when he met a fellow Rotterdam native at the gym, they immediately became best friends. “You can get by quickly in a supermarket in another language, but maintaining a friendship in a different language is complicated. Humour and complex conversations require such a high level of language.”

The Netherlands as coloniser

As an NT2 teacher, he analyses Dutch as if it were a foreign language. Sentence structures that once felt self-evident, he had to relearn during his teacher training, so he could then teach them to newcomers. However complex that may be, at least it’s unambiguous. Dutch cultural norms are less so, Van Leeuwen realised while listening to the podcast series Revolusi by author David Van Reybrouck during a holiday in Indonesia. “Fifty percent of Dutch people are still proud of the colonial past”, he says. “I didn’t expect that.”

After listening to the more than eight-hour podcast Revolusi about the history of Indonesia, Van Leeuwen also read the book of the same name by David Van Reybrouck. The author interviewed hundreds of still-living witnesses of the struggle for independence. It was precisely those personal stories that kept Van Leeuwen – not an avid reader, as he admits – reading. “The death of one man is a tragedy; the death of a million is a statistic”, explains Van Leeuwen, describing his interest in the book. He also sees a link with his own work. “All those stories are about war, migration, globalisation and fleeing. All themes that my students, unasked, are also confronted with.”

The classroom revolves around language

Van Leeuwen likes to read about genocide and war – even before going to sleep. “I dream about Putin. It’s probably something for a psychiatrist to analyse, but it occupies my mind.” When he drives to the golf course with a friend, they first discuss the latest situation in Gaza and Ukraine. But he doesn’t discuss geopolitical issues with his students. “Sometimes we watch the news in simple language. I always skip a report about Gaza then. It’s about the language”, says Van Leeuwen. “About speaking and listening. I spend much of the time trying to reduce speaking anxiety. That means correcting as little as possible.”

Whatever else happens above people’s heads doesn’t matter in the classroom. War, genocide and the colonial past of the Netherlands are all his personal interests. As is Boer zoekt vrouw. He recently read Boer zocht vrouw, the untold stories of the television programme that Van Leeuwen used to watch every Sunday evening with his friends. For a long time, the programme shaped his view of the Dutch farmer, but nowadays he also sees farmers as people driving their tractors onto the Binnenhof. It’s just as well that in his lessons he can stick to the Dutch language. He’d rather not burn his fingers on Dutch culture.

Reading habits

Reading habits

Number of books per year: Five to ten

Last book read: Boer zocht vrouw by Chris van Mersbergen

Main motivation: Relaxation – despite the choice of topics

Favourite genre: Non-fiction about genocide and war

Read more

-

The digital reality can be deceptive, knows Ofra Klein

Gepubliceerd op:-

Page-turners

-

De redactie

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in Page-turners

-

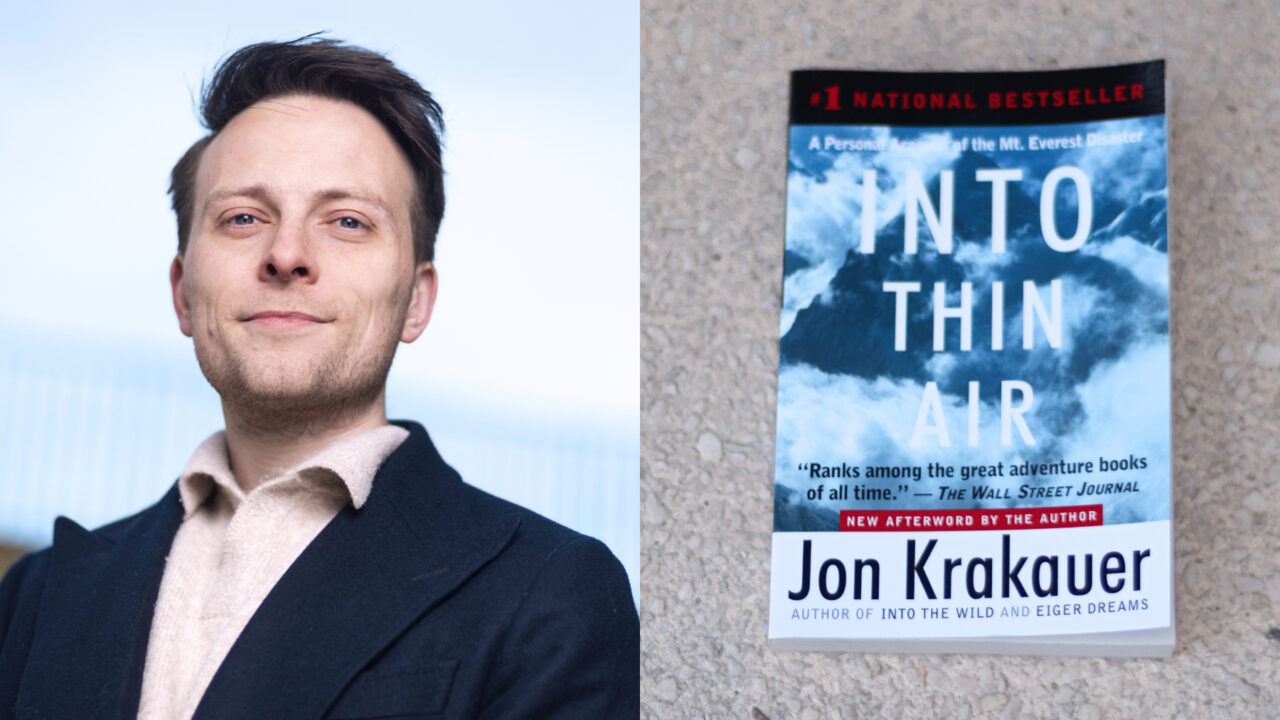

Why scientists are sometimes like Sherlock Holmes

Gepubliceerd op:-

Page-turners

-

-

People sometimes make unpredictable choices, Dominic van Kleef knows

Gepubliceerd op:-

Page-turners

-

-

Lives are full of change, and that’s why Yara Toenders is researching the brain

Gepubliceerd op:-

Page-turners

-