Why French politics is faltering under pension pressure

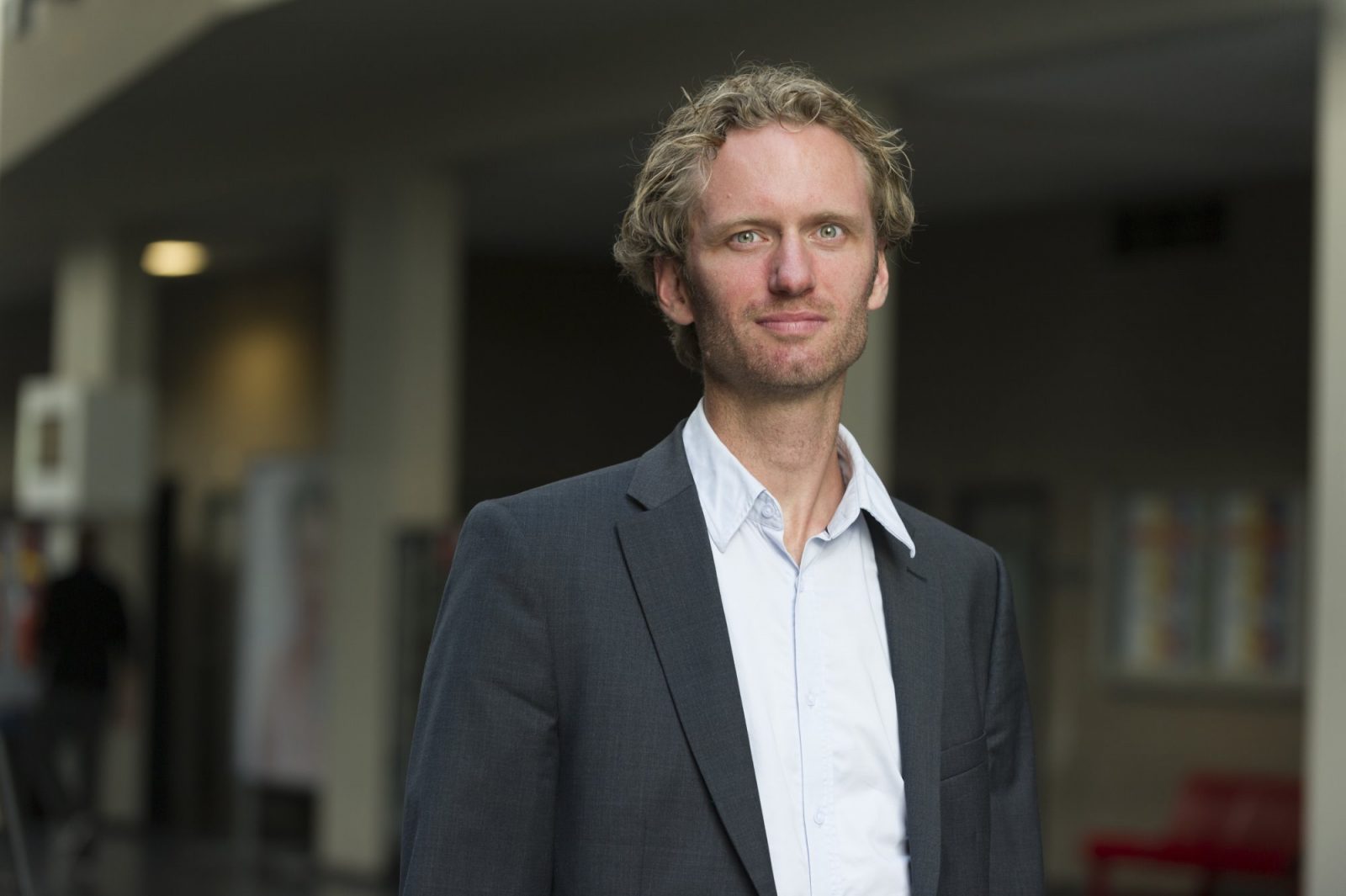

Growing public debt, a downgrade in credit rating and a political stalemate that is blocking reforms. Economist Casper de Vries explains what has been happening. “This is not a financial crisis, but a crisis caused by people who don’t want to work.”

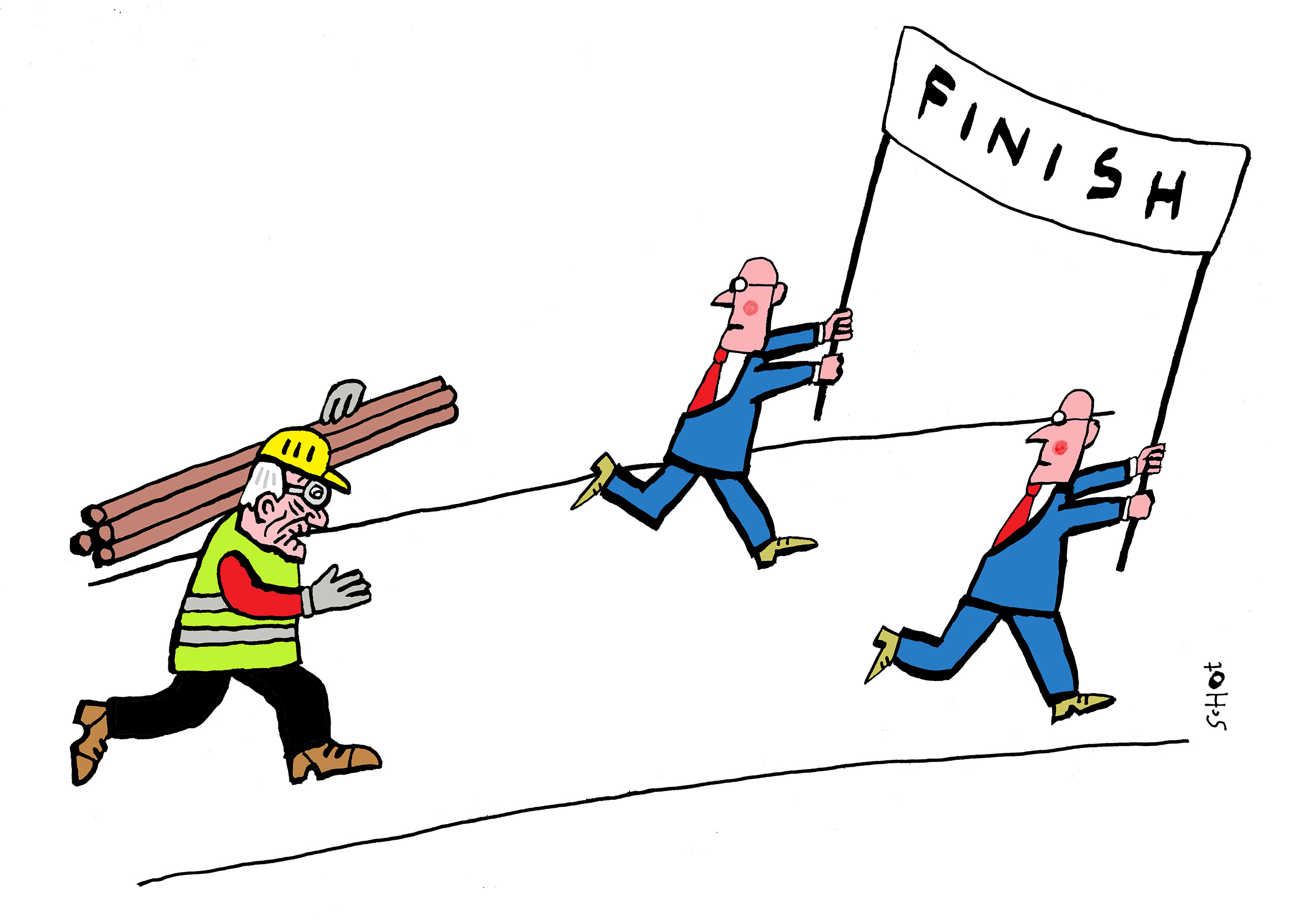

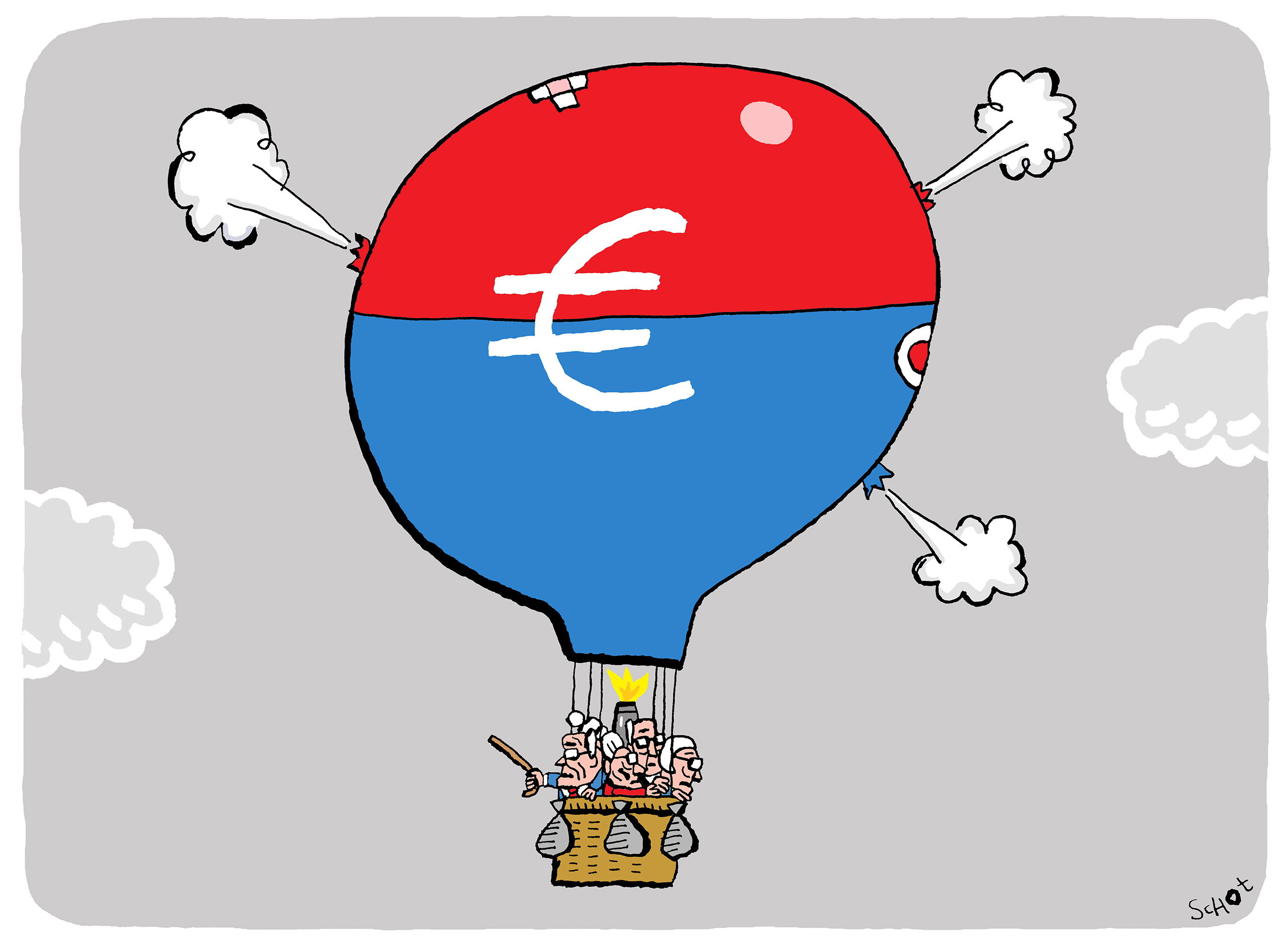

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Casper de Vries is emeritus professor of monetary economics at the Erasmus School of Economics and a member of the Dutch Scientific Council for Government Policy. His research focuses on financial markets, monetary policy and eurozone stability. He is also an adviser to two Dutch pension funds.

What exactly is going on in France?

“France has a high level of public debt and it is still rising, mainly due to high pension spending. An ageing population means there are more and more pensioners for each working person. Within 30 years, a working person in Europe will have to contribute on average twice as much in pension payments for retirees as today, which puts a huge strain on the economy. But young people aren’t willing to pay that, and older people don’t want to sacrifice any of their pension. So, there are conflicting interests.

“Then a country has to borrow. And if it doesn’t implement pension reforms, national debt rises. In the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, the situation remains reasonably sustainable, with public debt below 100 per cent of gross domestic product. But in France, the debt will rise to as much as 200 per cent of GDP if policy doesn’t change. And that’s exactly the problem.”

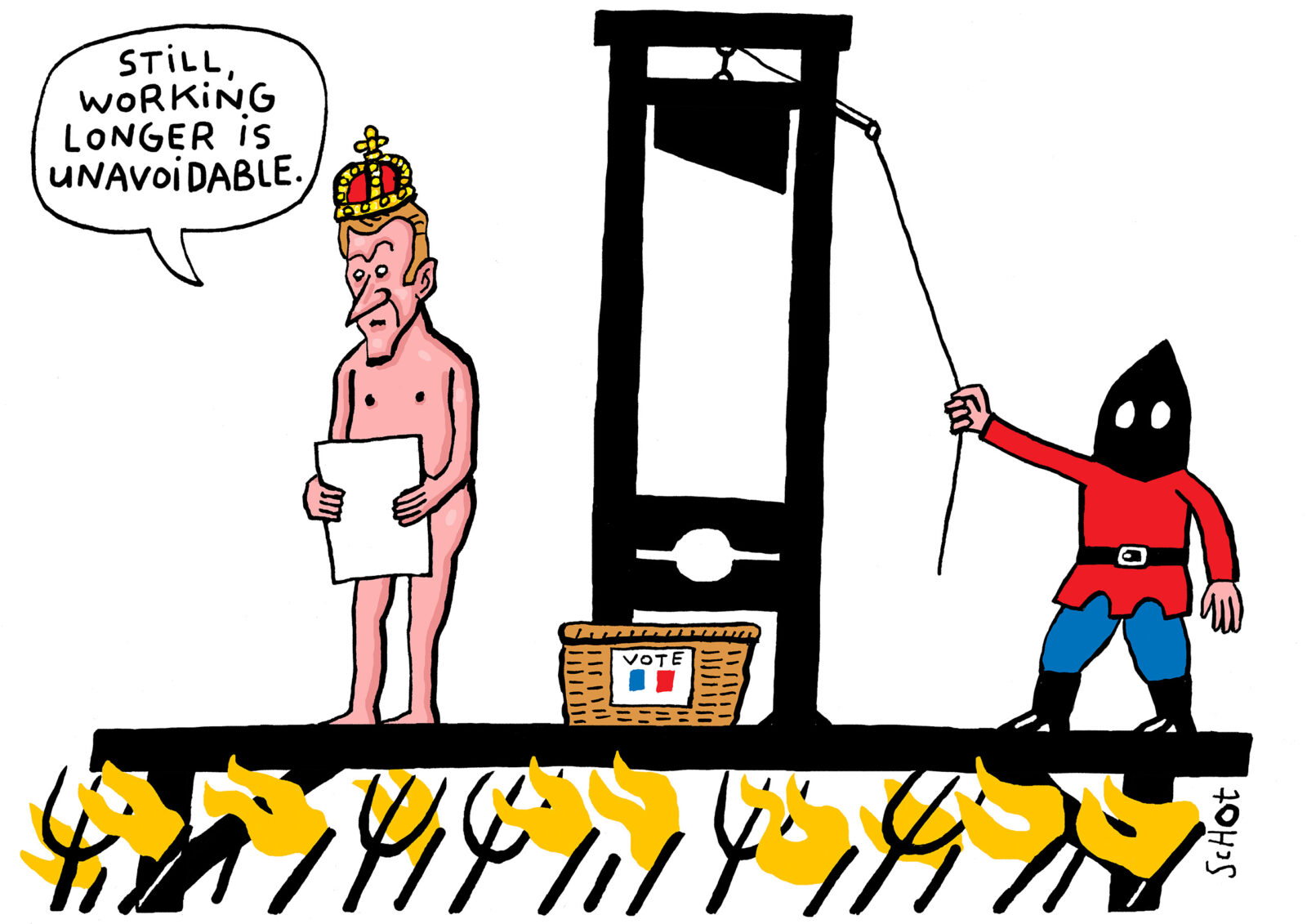

Image by: Bas van der Schot

So no reforms will be passed because of the political deadlock?

“Yes. Macron lost his majority in the National Assembly, France’s lower house of parliament, in 2022. Under Macron, Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne introduced a new Pensions Act in 2023, without the consent of parliament. In essence, the retirement age in France is now 62 but under the reform, it would rise to 64.

“It prompted widespread protests. Macron lost a great deal of his popularity and appointed a new prime minister to calm the situation. We have now had three prime ministers, but parliament continues to vote against reforms and other unpopular measures. Sébastien Lecornu has been prime minister since September. His first cabinet collapsed after 26 days and he has now been prime minister for the second time since 10 October. He has said he won’t be withdrawing the reforms, but he is putting them on hold for now. That may be a political survival strategy but at some point, the tide will turn.”

Surely there are EU rules on keeping sovereign debt in check?

“Yes, those agreements were made before the euro came in; it’s called a stability and growth pact. It’s a complete sham; France has never complied with it and the European Commission has never taken France to task for that, probably because we need France in the EU too much.

“Now we see the market doing the dirty work that the pact should be doing. Credit rating agencies see that France’s sovereign debt is becoming unsustainable and because it doesn’t look like the reforms will be passed anytime soon, they have downgraded France’s credit rating.

“They base that rating on the state of the economy and the level of debt. If a country borrows to invest in growth, the debt often remains sustainable. But France borrows mainly to pay pensions. And what do older people do with that money? Yes, going on trips is fun, but ultimately someone has to pay for it, which creates tension in the economy and impacts the country’s credit rating.”

What’s so important about France that the European Commission can’t hold it to account?

“Well, we in Europe have to work together for all sorts of reasons. Putin’s and Trump’s recklessness makes it clearer than ever that Europe has to stand united in geopolitics and defence. And we also need each other economically. Why are we missing out on this whole AI revolution? Because we have no scale. Everything is done individually, country by country. In America, something new can be rolled out instantly to almost 300 million people. Europe’s single market is important too; we export a lot to France, so any recession in France will easily have a knock-on effect in the Netherlands. So you can bash the French for their budget management skills, but at the end of the day, we need each other.”

Will France become the next Greece? Should we be worried about another euro crisis just like the one there?

“France already has to pay higher interest rates on its government bonds, but that hasn’t spiralled out of control like it did for Greece. If national debt becomes too high, you as a country end up in a very vulnerable position. All it takes is a single event, say a volcanic eruption in Iceland or a Russian invasion somewhere, and interest rates shoot up worldwide. Then suddenly, you have to pay much more interest and your national debt becomes unaffordable. It’s hard to know where the point is when everything collapses. But the higher the national debt, the sooner that point will come.”

‘If France fails to make structural changes, other eurozone countries will end up paying the price’

What role does the European Central Bank play in this whole affair? Should it step in, as it did during the euro crisis and the coronavirus pandemic?

“Not at all. The ECB has only one objective and that is price stability in the eurozone. When country interest rates begin to drift too far apart, the ECB can step in with a temporary measure, buying French government debt to stabilise the situation. But if France fails to make structural changes, other eurozone countries will end up paying the price.

“I don’t know whether the ECB will stand firm on not buying up debt. I honestly don’t think it will. I felt the debt buying during COVID was excessive, although not every economist agrees with me. But that’s one of the reasons we are now stuck with such high inflation.”

What do you mean by that?

“In the pre-war depression, many economists and politicians developed tunnel vision. Everyone thought you could use monetary policy to stimulate demand in the economy. Low interest rates, more credit, more investment, more consumption. But now practically everyone is working, so monetary policy has no effect at all and then you only end up with inflation.

“Tinbergen had a rule that said you should use a separate instrument for each problem. The ECB uses its interest rate policy for price stability. And individual governments are responsible for their own budgets, so they have to control that budget themselves. And it would not be right to mix monetary policy with public finances. You can use monetary policy during a financial crisis, but what is happening in France is not a financial crisis. It’s a crisis caused by people who don’t want to work. France has brought this on itself and the only way to address that is by working for longer.”

That’s quite a clear message. But it doesn’t look like that is going to happen in France. How do you see a way forward?

“In France, there are three blocs, none of which has a majority, and they are completely unwilling to work with each other.” Macron is right in the middle and his support has shrunk enormously. On the left, you have Mélenchon, who is fiercely opposed to reforms. And on the right, you have populists like Le Pen, who, like Wilders, act as if everything in life is free. They have these grandiose plans, but they never say where the money would come from.”

“There’s quite a big chance that Le Pen will come to power, but ultimately it doesn’t really matter who wins. It looks like this will take another 30 years. By that time, this generation of pensioners will have passed away and the demographic composition will be straightened out again. Fortunately, I don’t have to predict whether France can ride it out that long financially.”

There is also a lot of political instability in the Netherlands and populism is gaining a foothold. How likely is it that the Netherlands will end up in the same position as France?

“The right-wing PVV also says they want to increase pensions and lower the retirement age. Suppose they came to power and wanted to roll back pension reforms… the Netherlands would be in some serious fiscal trouble.

“Luckily, the Netherlands is faring better than elsewhere in Europe for two reasons: Our population is not aging as quickly and we’ve saved more for our pensions. Other countries pay for pensions from their current budget. i.e. working people pay for those receiving pensions in the same year. In the Netherlands, we do the same with our state pension, but the rest comes from pension funds that have already been saved for.

“And in the Netherlands, we did raise the retirement age and we have already abolished all kinds of counterproductive schemes like early retirement. So, now we are top of the class. The employment rate of older people in the Netherlands is the highest in the EU. which is partly the reason why our national debt won’t go through the roof if we don’t make any further reforms.”

‘Labour migration from Poland, Romania and Bulgaria is going to dry up within a few years’

If the Netherlands is an exception in Europe, how will we feel the impact of our neighbours getting older?

“Eastern Europe is ageing faster than anywhere else in the whole EU. Labour migration from Poland, Romania and Bulgaria is going to dry up within a few years. So, those parties who want less migration are going to get their way, especially if we keep the external borders closed. But we will end up paying for that. Vegetables will become more expensive if nobody wants to work in agriculture anymore. Housing will get more expensive if we don’t have enough people in construction. We are going to feel the effects of ageing in Europe, so we need to be working for longer here too.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

So, should the retirement age in the Netherlands be raised even further?

“That will happen eventually. The retirement age of 65 was introduced in Germany by Bismarck in 1889. Back then, only a few made it to that age, so it was affordable. But that number is not set in stone. The good news is that we are now living 20 years longer ‒ health permitting ‒ and are able to work longer. But that’s not the only solution: we can also involve more people on the sidelines, such as asylum seekers.”

You sound pretty optimistic despite the economic problems. Why is that?

“People act as if working is a bad thing, but the good news is that the economic problems we currently face can be solved by working for longer. And yes, that is actually a very positive message. There are all sorts of studies that show working after 60 is good for you ‒ not so much in physically demanding jobs. In fact, we should allow road workers to do their job until they are 40, as used to be the case for firefighters and military personnel, and then support them in retraining for another profession. It’s also our duty as a society to support people who are sick. But for everyone else: we need to keep working. I am 70 and technically retired, but I’m still working. Working is great fun, and it’s good for you.”

Read more

-

‘Artists like Bob Vylan and Kneecap are more than just a mirror of society’

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

De redactie

Latest news

-

Students volunteer at IFFR: ‘I saw Cate Blanchett right in front of my eyes’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Culture

-

-

Jacco van Sterkenburg is the new Chief Diversity Officer

Gepubliceerd op:-

Diversity

-

-

‘Without journalism we are dependent on people with power’ – This is why we need journalism (episode 1)

Gepubliceerd op:Article type: Video-

EM TV

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

‘Artists like Bob Vylan and Kneecap are more than just a mirror of society’

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-