This is what Rotterdam needs to do to help its citizens become healthier

Image by: Bas van der Schot

With large-scale cohort studies like ERGO and Generation R, Erasmus MC is one of the leading institutions worldwide in the field of public health research. But the results of this scholarship don’t always trickle down to the man in the street. Why is that? Lex Burdorf: “It took us a while to realise the professionals wouldn’t be beating a path to our door for our findings.”

Lex Burdorf is Professor in Determinants of Public Health at Erasmus MC. He is currently researching which influence socio-economic factors, the environment, local air quality and behaviour have on our health and life expectancy. Burdorf also works as the coordinator of CEPHIR. In this ‘academic workshop’, Erasmus MC’s Department of Public Health and the Rotterdam-Rijnmond Community Health Service (GGD) perform joint research into public health.

How healthy is Rotterdam?

“In the Netherlands, the average male lives to 80, and the average female to 84. In 2008, I calculated that in Rotterdam, life expectancy is 18 months shorter on average. And this is still the case, although we’re still comparable with a lot of other cities like Maastricht or Enschede, incidentally. Rotterdam scores worse than average on every major disease. We have more cases of cardiovascular disease. More respiratory conditions like asthma and COPD, particularly later on in life. And a slightly higher percentage of cancer, but above all, a higher cancer mortality rate.”

A few years ago, you made an overview of health differences within Rotterdam itself for a lecture. It painted a grim picture.

“We mapped out the average life expectancy at locations along Rotterdam’s underground network. It turns out that on average, residents near the Nesselande terminus live almost eight years longer than people living near the Maashaven underground station. Eight years, within a single city. That’s the same difference that you see – in fact, it’s even slightly greater – between people who only have primary school education and those with an academic degree.”

‘Residents in Nesselande live almost eight years longer than people near the Maashaven. Eight years, within a single city!’

At one time, the city’s main employer was the port. Nowadays it’s the medical cluster. To which extent are these researchers and physicians actually concerned with public health in Rotterdam itself?

“The town is frequently used as a laboratory. Individual researchers do projects in the city and confer with the Municipality about metropolitan health issues within academic workshops. What really distinguishes Rotterdam from other cities is that we have set up a number of large-scale, long-term studies: cohort studies in which a group of people are followed for years on end. Generation R, for example, maps out the effects of lifestyle, environment and socio-economic factors on children’s development – starting as early as the mother’s pregnancy. Ergo, another cohort study, have already followed a group of 15,000 senior citizens from Ommoord for close to 30 years – to gain insight in the development of dementia, among other things. A programme I myself am involved in is the academic workshop CEPHIR. Here, we study the entire chain, from cradle to grave, together with a number of partners, including the Community Health Service (GGD). Internationally, the findings of studies like these are extraordinarily important – mainly thanks to the quantitative data that they produce. While other countries may have even larger-scale cohort studies, few of them have yielded as many academic publications as these programmes.”

You seem very proud. But these publications tend to be English-language articles in international journals. So what happens next?

“At one time, our idea was: if we produce significant research results, the professionals will beat a path to our door. They’ll use our data to finally solve the problem. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Why is it that this knowledge often isn’t put to practice?

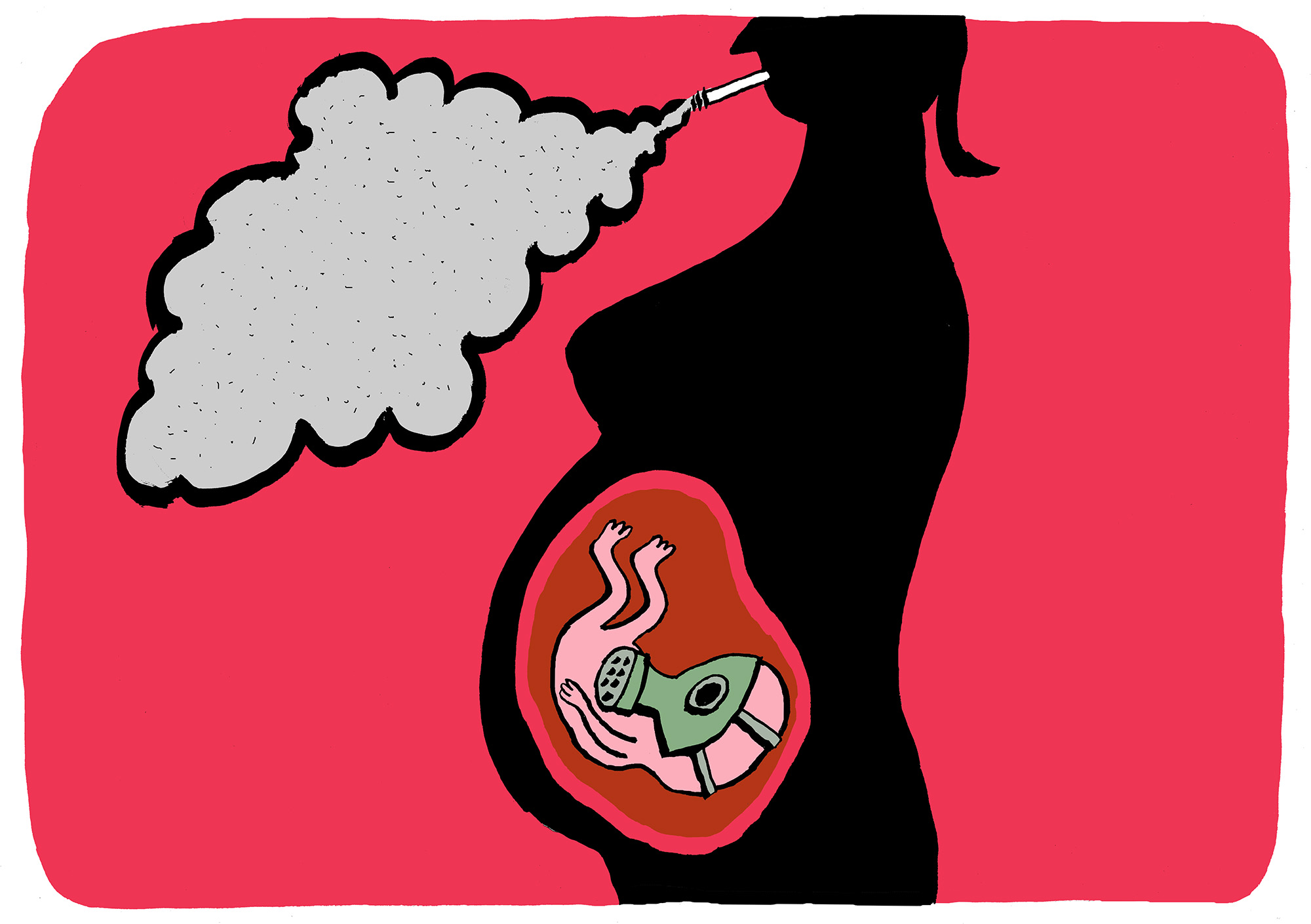

“There are a number of reasons. The first is that insight doesn’t automatically lead to new policy measures. For example, we know that smoking is very bad for you. Nevertheless, a lot of women in Rotterdam still smoke during pregnancy. A variety of programmes have been launched, including Stevige Start and Klaar voor een Kind, which focus on developing better interventions. For example, by now we know that it doesn’t work to tell people that smoking is unhealthy and expensive. When you can’t pay the rent and are busy making it through the week, you actually smoke for a kind of release. That means you first need to take away the causes of this stress – by getting people into a debt restructuring programme for example. But that’s easier said than done.

“On top of which: the people who could actually set to work with our findings – obstetricians, GGD policy staff, youth welfare workers – are horribly busy as it is. Take youth welfare, for example. Over the past two decades, these organisations have undergone one budget cut after the other. Counsellors need to account for their activities – down to the minute. And then we turn up with some new idea they’re supposed to invest their energy in? I don’t think so.

“It’s difficult though. There you are with your knowledge. You know why people are less healthy; why their children grow up less healthy – but there’s nothing you can do about it. Or rather, you can only do so much about it.”

Do you see it as your duty as a scientist to think about solutions?

“I believe so, yes.”

How do you go about this?

“When they were working on the environmental zone, the GGD asked me whether I wanted to think along about health aspects that could be used to substantiate the decisions. In cases like that, I provide the responsible Deputy Mayors – at the time Pex Langenberg and Hugo de Jonge – with relevant information. And if they ask me to hold a presentation at a public meeting, I tend to say yes. Generally, these meetings are also attended by concerned shopkeepers who are worried about their turnover. Whenever someone questions whether an environmental zone like this actually has any effect – and why not, because it’s very difficult to attribute an improvement in public health – I enjoy showing them how many so-called ‘silent wins’ we’ve already achieved. For example, I tell them that thanks to these kinds of measures, the average Rotterdammer’s life expectancy has risen by five years over the past 25 years: ‘this means that nowadays, the Mayor fêtes someone who’s turned 100 every day. In the old days, it was once a month.’ That’s what I tell them. That sort of thing really brings it home to people.”

‘Wetenschappers hebben nogal eens de neiging om iets uit te leggen met twaalf nuances’

Is that true?

“Yes. Local air quality has improved tremendously. Particularly thanks to advances in combustion technology: despite all the discussions about fraudulent software, modern cars are a lot cleaner than they used to be. The transition from coal to gas has yielded huge health wins. In the old days, cities were literally black with soot. One year of the aforementioned five comes from cleaner air. But stuff like this needs to be clearly communicated. Scientists tend to make all sorts of distinctions when they explain something. While the only thing the average listener wants to know is ‘Are we going right or left?’.”

Imagine the new Deputy Mayor asks you to draw up a plan of action for improving public health in the city. Policy measures that will have a major impact. What would you advise him or her?

“As far as public health’s concerned, smoking remains the number one determinant for an unhealthy life. So I’d propose a very strict anti-smoking policy. Ban smoking in the Koopgoot and on Coolsingel. Same thing for schoolyards. And the area around Erasmus MC. In a city like New York, people have gotten used to the fact that you’re not allowed to smoke in Central Park. You can help people kick their addiction with measures like that.

“Secondly, I’d invest heavily in participation. If there’s one thing that’s bad for your health, it’s long-term unemployment. You live a short, less healthy life; you’re at a greater risk of developing depression, cardiovascular diseases. Money is only part of the story, by the way. In fact: if you could decide between a basic income of 1,000 euro, so that someone doesn’t have to worry about money problems, or a job that pays 600 euro a month and keeps that person occupied throughout the day, I’d always go for the second option.

“My third point would be that all children should get a good start in life. When you hear that some children are sent to school without having had any breakfast – with a can of energy drink – you can’t afford to ignore that kind of thing. I would argue for a school breakfast programme. That may sound unorthodox, but I believe measures of this kind are necessary in a town like Rotterdam.”

Could you examine your own conscience for a moment: what can the scientific community do when it comes to improving how knowledge is put to practice?

“It’s great that Erasmus MC’s mission statement says that Rotterdam is very important, but the Executive Board should put their money where their mouth is and reserve a structural budget for programmes in the city. Right now, too much hinges on a handful of enthusiastic professors. Eric Steegers at Obstetrics, Jan Hendrik Richardus at Infectious Diseases, Patrick Bindels at the Department of General Practice. They don’t actually have to do all the things they do – they feel a responsibility to contribute to a healthier city. They do wonderful work. But at the same time it’s vulnerable, because it isn’t organised and funded on a structural basis. Why not simply allocate 200,000 euro a year to these academic workshops? Clinical researchers find their patients in the hospital; we find them in the city.”

The Municipality of Rotterdam attaches strong importance to knowledge-driven solutions. The administration has set up all sorts of partnerships with universities of applied sciences and research universities. How could officials take better advantage of all the academic knowledge that has been amassed about the city?

“Right now, I sometimes get the feeling that politicians aren’t so much trying to solve a problem as pursue a specific vision – and they expect scientists to supply arguments in support. Take the environmental zone I mentioned earlier. One of the parties in the Municipal Executive (Leefbaar Rotterdam, eds.) believed it was in its constituents’ interest to exempt mopeds from the environmental requirements. Well… you only have to stand near a scooter idling at the traffic lights for a short while to understand that that’s a bit strange.

“In addition, the Municipality has no problem with cooking up new policies, but they should also take a good look at existing measures every now and then. I believe you have a responsibility to show that what you’re doing actually works, and who benefits from it.

“But the most important thing is probably that people need to understand that there’s no ‘silver bullet’ for our problems – no measure that can solve everything in one fell swoop. We’ve researched whether neighbourhood football pitches throughout the city lead to more physical activity. The answer: yes, they do – to the amount of an extra hour a week. A lot of people are disappointed when they hear that. They don’t think an extra hour is anything to write home about. But that’s about as big an impact as you can get with a single measure. This environmental zone will result in a demonstrable reduction of soot and airborne particulates in the city centre. If you were to calculate what the immediate impact of these reduced emissions is, you’d arrive at maybe ten fewer hospital admissions per year. At which point, you might say ‘Are we doing all of this for that result?’ Well, yes: that’s how it works. With each new measure, everyone’s life gets a tiny bit better. So if you want to see a lot of improvement, you need to take a whole bunch of small steps.”

De redactie

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-