‘In several healthcare plans in the coalition agreement, I see the risk that vulnerable groups will be hit the hardest’

A higher deductible excess, a sugar tax and a personal contribution for district nursing: the new cabinet is intervening firmly. According to health economist Sander Boxebeld, it is good that the coalition is making clear choices in healthcare. But whether those choices will be fair is another matter: “Ultimately, it comes down to who retains access to care, and who will bear the heaviest burdens.”

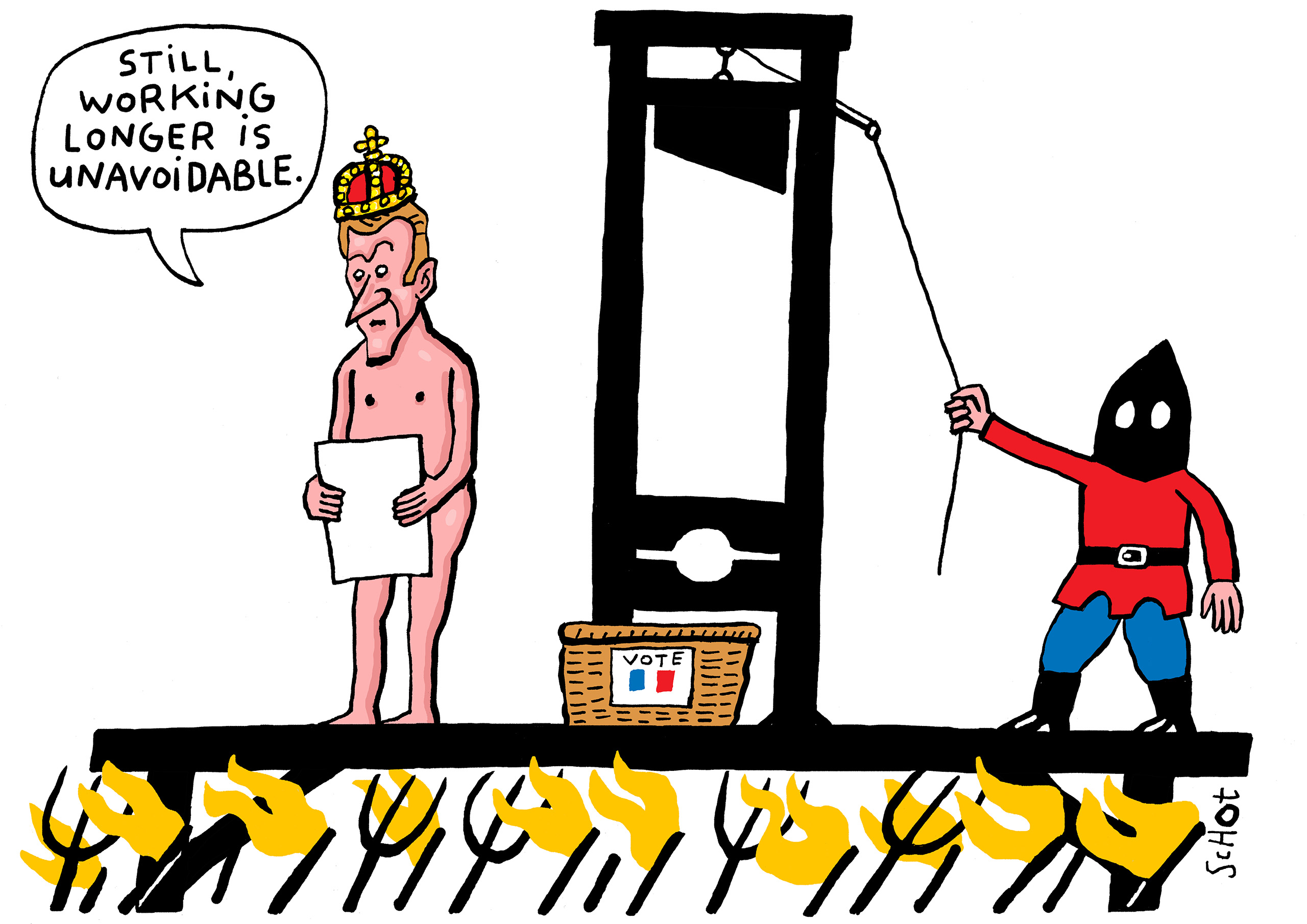

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Sander Boxebeld is an assistant professor of Health Economics at the Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management. He studies how people think about healthcare policy, the distribution of healthcare costs and what that means for political choices.

Is the new cabinet actually cutting healthcare spending?

“After defence, the coalition is allocating the most money to healthcare. And after defence, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport is also seeing the largest increase in the government budget. So in absolute terms, more money is going to healthcare than before. But partly due to ageing, demand for care is rising sharply. That means less money is available per person in need of care. To address this, the coalition is making choices that will hurt people in one way or another.”

How optimistic are you about the coming cabinet period for healthcare?

“I think it is good that the coalition dares to make tough choices on certain points. Such as the sugar tax, the deductible excess, and the personal contribution in district nursing. That does not mean I would personally choose all of those measures, but it’s good that they are making decisions and not postponing problems. But as far as I am concerned, the plans will stand or fall on the question of who ultimately retains access to formal care, and how the burdens will be distributed. In several plans in the coalition agreement, I see the risk that vulnerable groups will be hit the hardest. That won’t be the coalition’s intention, but it really requires careful attention to those groups when implementing the plans.”

'The danger, however, is that people will avoid care because they can’t afford their excess'

The excess is rising from 385 to 460 euros. That will be a setback for many people. What do you think of that measure?

“It is a striking political choice, given that the previous cabinet had plans to halve the excess. On the other hand, there will be a maximum of 150 euros per medicine or treatment under the excess. There is something to be said for that. The idea behind the excess is to make clear that care is not free and to create an incentive not to use more care than necessary. If you’ve already used up your excess at the start of the year, you no longer have that incentive for the rest of the year. The danger, however, is that people will avoid care because they can’t afford their excess. People on lower incomes are relatively the hardest hit by this measure, even though an increase in the healthcare allowance will partly compensate for that.”

Does demand for care really rise if the excess is lowered?

“That is difficult to study, because such measures apply to all Dutch residents. So you do not have a control group. And the excess is often not the only thing that changes under a new cabinet, so it is hard to establish a causal link. In the 1970s, ethically questionable experiments were conducted in the United States, for example by not introducing such an excess for everyone at the same time. Those did find a link between a higher excess and lower healthcare spending.”

Another eye-catching measure is the sugar tax. Does such a tax improve public health?

“Overweight is increasing in the Netherlands, to 62 percent of the population by 2040 according to the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Meanwhile, the National Prevention Agreement sets a target of 38 percent. The current agreements are therefore not enough to achieve that goal, so something else will have to happen. “Sugar plays an important role in this. Whether a tax leads to lower consumption depends on how it is introduced. In England there is a tax on sugary drinks. In the Netherlands, it still needs to be worked out in detail, and it will probably also apply to pre-packaged foods. That would have more impact. But will frozen fruit also be taxed? And which alternatives will people choose? If nothing is done about other unhealthy foods, such as crisps and fast food, it will be less effective.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

I am surprised that the sugar tax, a measure that is quite paternalistic, is coming from a coalition that includes two liberal parties. Where does this measure suddenly come from, and is there public support?

“I suspect the idea from D66 is that this could reduce socio-economic differences in health. But the danger is that people on lower incomes are relatively harder hit by such a tax than those on higher incomes, because they spend a larger share of their income on groceries, and therefore also on sugary products.

“I have already seen negative reactions, with people wondering whether they are being punished by the government. Discouraging measures like this are generally unpopular. There is more support for encouraging measures, such as making healthy products cheaper, or making sports facilities more widely accessible. Research does show that support increases if the government uses the revenue from the tax for prevention or healthcare.”

Will the new cabinet do that as well?

“It’s striking that the sugar tax wasn’t mentioned specifically in the chapter about health and care, but appears in the financial section of the coalition agreement. It is expected to generate around 50 euros per citizen per year. The coalition has already factored in those revenues. It states that part of the proceeds will go towards prevention, but it’s rather vague about how much it means by ‘part’. They give the provision of free fruit in schools as an example. That is quite a cost-effective measure, but it feels like a drop in the ocean.”

Is prevention actually a good way to reduce healthcare costs?

“In public debate, that is often how it is presented. But in health sciences we see that this is not always the case. Put bluntly: if you prevent someone from having a heart attack, but that person then develops cancer, you are probably spending much more on that patient than if you had not prevented the heart attack. And if you then manage to prevent that cancer, people will live longer and use more long-term care.

“But that doesn’t mean you wouldn’t want to prevent a heart attack. Aside from keeping people healthy, it also has economic benefits. Prevention ensures that we’re more productive. People report sick less often, are less likely to become unfit for work, they can more often provide informal care, look after grandchildren or do voluntary work. So prevention is a good idea, but as a government you should at least be clear about where it brings returns.”

'In fact, recruiting enough healthcare staff is currently the biggest bottleneck'

Is the new coalition taking ageing sufficiently into account?

“In fact, recruiting enough healthcare staff is currently the biggest bottleneck. I don’t see much about that in the agreement. There are some plans, such as promoting work outside the hospital. That has been proposed before, so it’s not clear what will change in practice.

“The coalition agreement does pay a great deal of attention to long-term care. For example, the coalition wants a greater role for the community in supportive care, such as helping out with groceries. It’s not really clear what that should look like. Funding has been set aside, so now the key is to ensure it doesn’t become an empty promise.

“The cabinet also wants to encourage older people to live at home for longer. That is often what people themselves want. But it also puts greater pressure on hospitals, because, for example, older people with a broken hip cannot return home as quickly if they are still living independently. And if older people live at home for longer, we need more informal care. That isn’t free either. It requires a cultural shift. In the Netherlands, we were not at all used to caring for our own elderly people, although that is increasingly happening.”

Previous cabinets also encouraged older people to remain at home for longer. What additional measures are still possible?

“Here too, the coalition is still vague and it will depend on opposition parties how it will turn out in concrete terms. For example, the cabinet wants people to pay a personal contribution for district nursing. It also states that it wants to further ‘separate’ housing and care. That could mean having to pay rent in a care home. The question with both measures is whether they will be income-dependent. Contributions in care homes are already partly income-dependent, but wealth is largely not taken into account. There is room for more solidarity there. The downside is that people on higher incomes might turn to private care providers if prices rise. In that case, solidarity also falls away.”

Read also

-

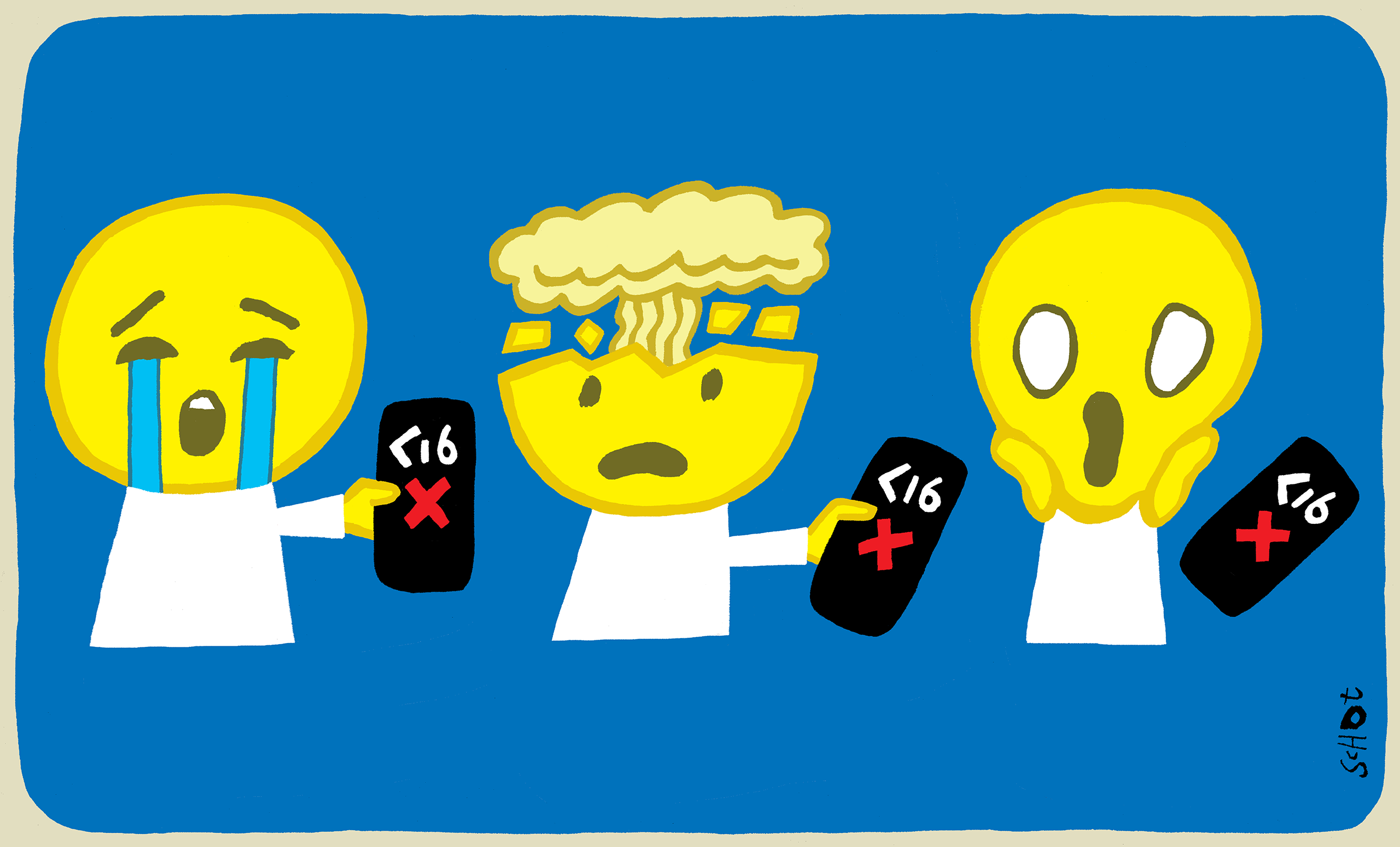

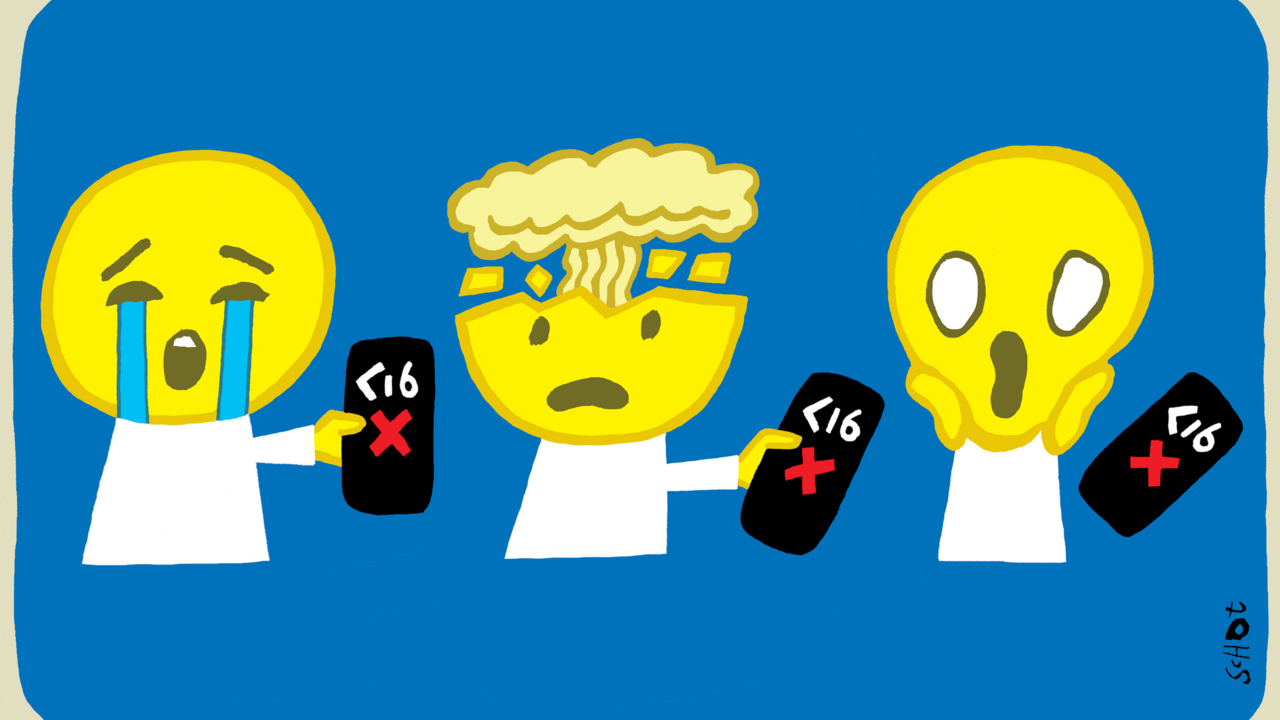

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

De redactie

Comments

Read more in The Issue

-

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

Why French politics is faltering under pension pressure

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

Leave a comment