‘The research I do always makes me feel that we’re getting closer to understanding exactly how the cerebellum works. I think that’s cool’

How does the brain learn? What exactly happens in the complex network of nerve cells when you master a new skill? Martijn Schonewille looked for the answer in the cerebellum, which is known for its highly organised structure. But how this well-organised machine actually works proved anything but simple.

Image by: Hilde Speet

The wonder

“What happens in your brain when you learn? I have always wanted to know the answer to this question. It’s clear that the cerebellum plays a crucial role. You could describe it as a kind of calculator that fine-tunes movements. I’m intrigued by how well-organised this part of the brain is. Unlike the cerebrum, which is a chaotic mess, patterns seem almost to be recorded in the cerebellum.

Martijn Schonewille is a professor of Neuroscience at Erasmus MC. He studies how the cerebellum contributes to motor skills, cognition and learning. He and his research group study how nerve cells in this brain region process information, among both healthy and ill people. Last month, the Dutch Research Council (NWO) awarded him a Vici grant to establish a line of research and strengthen his research group over the next five years.

“I actually already had a kind of reverse eureka moment while doing my doctoral research. I was studying the learning process in the cerebellum of mice. According to the prevailing theory, a weakening of connections between nerve cells, or long-term depression, was essential for learning. I tested this on mice in which this mechanism had been disabled. The results? The mice were still capable of learning.

“My findings caused a stir in the field. Some researchers struggled with the fact that a theory that had been accepted for 50 years was suddenly up for debate.

‘My findings caused a stir in the field’

“During my research, I noticed something: nerve cells at the front of the cerebellum fire much more frequently than those at the back. Initially, this didn’t seem particularly special, until I compared it with a long-established anatomical fact. The cerebellum is divided into stripes in which cells express either the zebrin protein or PLC-beta 4. This pattern had always been used as a kind of anatomical map: useful for pointing out where you were, but not of any real interest otherwise. However, I was still curious. What if those stripes actually tell us more? Not just the location of cells but also how they behave? Perhaps the researchers who rejected my findings were looking at completely different cell types without realising it.”

Read more

-

Three academics from Erasmus University awarded Vici grant for groundbreaking research

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

The research

“In the lab, we tested mice while they were learning. Part of the experiment involved a mouse sitting with its head fastened to a turntable. Around the mouse, there was a digital screen on which we showed different patterns. We carefully tracked the mouse’s eye movements whenever the turntable moved and changed what it could see. Eye movements are an ideal way of measuring how the cerebellum processes information, because the cerebellum controls them very precisely and predictably. So, you instantly see how learning and motor skills come together.

“To record a single nerve cell, we sedated the mouse and then made a tiny hole in its skull, directly above the cerebellum. We then inserted into the hole – with utmost precision – a wafer-thin glass tube filled with a saline solution that conducts electrical signals. This enabled us to capture the electrical impulses of a single nerve cell while the mouse moved its eyes.”

The eureka moment

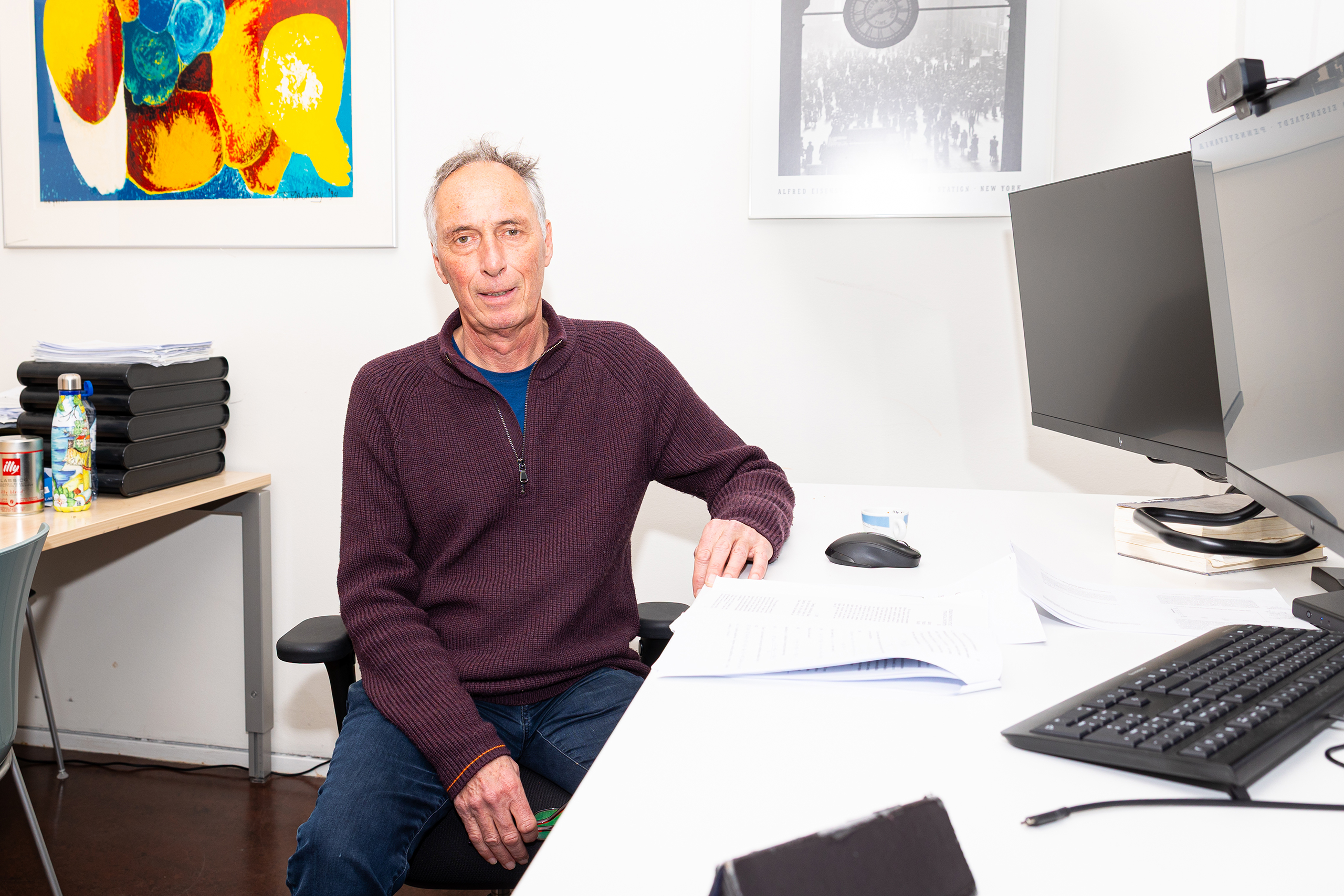

Image by: Hilde Speet

“Afterwards, we recorded the measurements and coloured zebrin and PLC-beta 4 proteins green and red, respectively. As each cell confirmed the pattern, I thought: ‘It couldn’t be, right? We must be doing something wrong.’ But as we examined more cells, a clear pattern emerged. Nerve cells containing the zebrin protein fired at a different frequency to cells without this protein.

“The real eureka feeling came when we repeated the test in slices of the cerebellum, separate from the information the cells normally receive. The differences persisted, even without external incentives. So, the variation was not due to the input received and was intrinsic to the cells themselves. We found that the cerebellum was not one homogeneous calculator and consisted of at least two distinct populations of nerve cells, each with their own character.”

The result

“For many years, neuroscientists believed it was possible to make general statements about the function of the cerebellum as a whole. However, our research shows that you need to know which ‘stripe’ you are looking at – zebrin-positive or zebrin-negative – before you can say exactly what is happening.

“We now know that this goes even further: there is evidence to suggest that there could be as many as nine different subpopulations. These differences affect fine motor skills, cognitive processes and even social skills.

Image by: Hilde Speet

“This could enable us to gain a better understanding of disorders in which the cerebellum plays a role, such as spinocerebellar ataxia, a genetic disease that disrupts motor skills, and even autism. In time, we may also be able to provide more targeted treatment.

“Sixty years ago, neuroscientists thought that we would have an almost complete understanding of how the cerebellum works by now. But we still don’t. However, the research I do always makes me feel that we are getting closer to this milestone. I think that’s cool.”

Read more

De redactie

-

Manon Dillen

Manon DillenEditor

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in Eureka!

-

Why the economy doesn’t belong to economists

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

Voters do make rational choices when they vote for populists, discovered Otto Swank

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

Why legal scholars, philosophers and empirical researchers need each other

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-