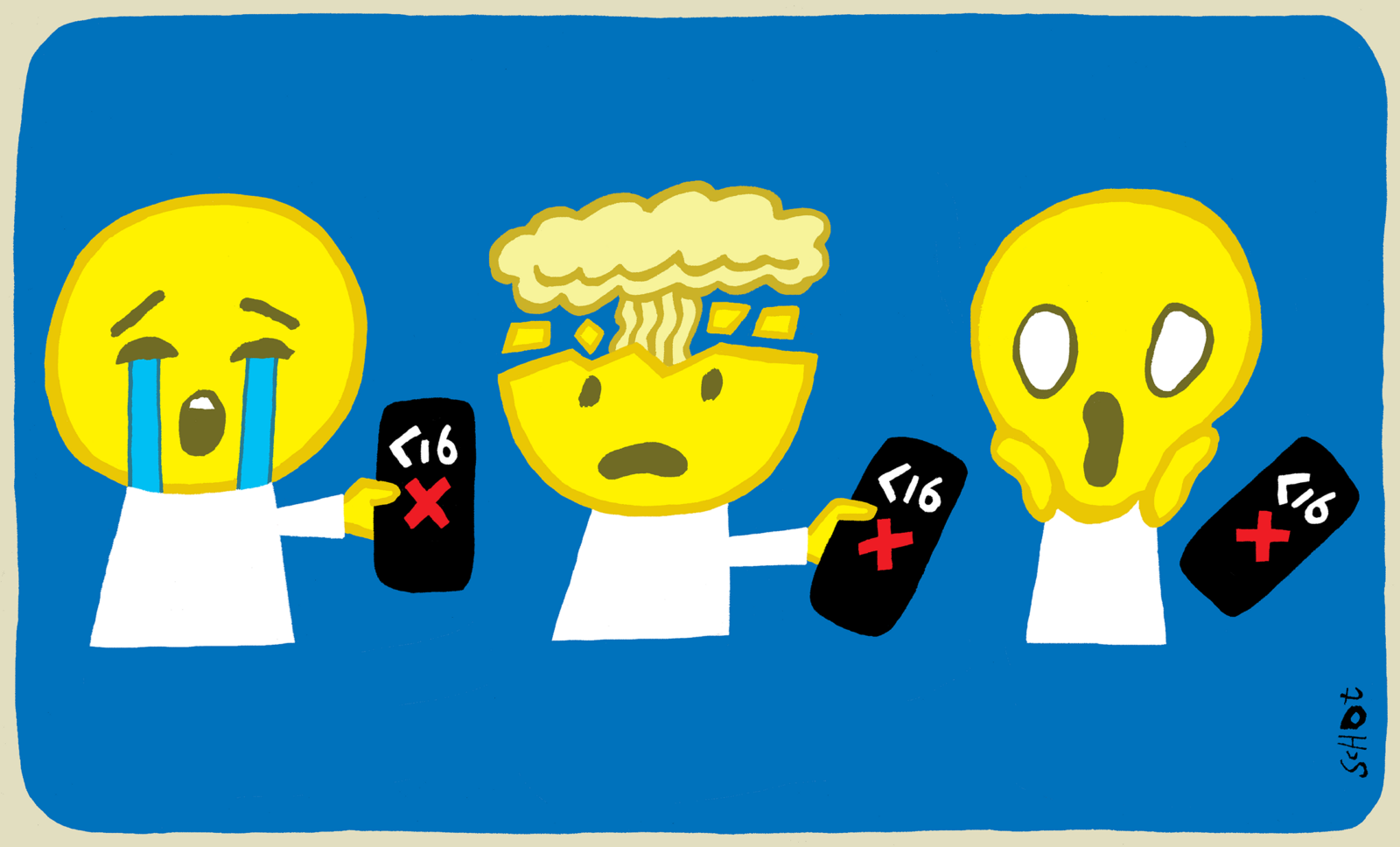

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Bullying, hate, shocking images and constant pressure to stand out – these are just some of the problems young people face on social media. Should social media be banned for young people? More and more countries are considering it, and Australia became the first country to introduce an age limit last year. But according to social behavioural scientist Esther Rozendaal, such a measure mainly offers a false sense of security.

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Esther Rozendaal is professor of Digital resilience and adaptability at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences. Her research focuses on the digital living environment of young people, the challenges they encounter there and how they can learn to deal with these in a healthy way.

Should social media be banned for young people?

“A ban or strict age limit for social media seems attractive, because it is a clear measure. Australia has introduced a minimum age of 16, which is based on limited scientific evidence by the way. I am very curious to see how that will work out there. During the introduction, we immediately saw how difficult it is to enforce such a ban in practice. Young people are very creative in getting around age checks, for example by using a VPN, getting help from older friends or, which was quite comical, setting up masks of older faces.

“There is no ‘magic age’ at which social media suddenly become safe. At seventeen it’s still not pleasant to see shocking content. A ban can actually make young people more vulnerable. They will do it secretly, without support from parents or other sources of help if something goes wrong. That shifts responsibility entirely onto young people themselves. Tech companies can then say that young people are not allowed on those platforms, so if they get into trouble it’s their own fault. Instead of banning everything, I believe the solution lies in making young people more resilient and better able to cope in their use of social media.

Young people get inspiration from social media, learn new things, improve their English and, last but not least, it is a major source of entertainment and relaxation

“Moreover, with a ban you throw the baby out with the bathwater. In the public debate there is little attention for the positive sides of social media. Young people get inspiration from it, learn new things, improve their English and, last but not least, it is a major source of entertainment and relaxation. Especially during secondary school years, social media play a major role in identity development. It is a practice space in which young people can explore who they are, who they want to be, and especially who they do not want to be, and can try out how their environment responds to that. That can have very positive effects, for example through self-expression and recognition.”

What are the problems young people encounter in their use of social media?

“That differs greatly by age, platform and child. Even in primary school you already see big differences: some children have a smartphone, others do not. But some are active on gaming platforms such as Roblox or Fortnite, which also have a strong social component. It is precisely there that children come into contact at an early age with unpleasant interactions such as cyberbullying, name-calling, but also sexual approaches, such as requests for nude photos. At secondary school this increases, especially when young people start using Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok more. Then it also explicitly involves hate, discrimination and racism, both from people they know and from strangers.

“In addition, young people are often confronted with intense content. On platforms such as TikTok and YouTube, violent images of, for example, animal abuse or sexually suggestive videos can suddenly appear, with varying effects: one young person finds this disturbing, another finds it exciting. Many young people also feel uncomfortable sharing their location, which is very common on platforms such as Snapchat. And online safety plays a role, such as fear of hacking or losing accounts. Finally, young people themselves are often really not happy with their screen time and feel they spend too much time on their phone.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

How resilient are young people to the challenges of social media?

“Young people do have ideas about how they should deal with the apps: setting a time limit, blocking or reporting someone, taking distance from a platform, or asking adults for help. Especially that last option is often mentioned by both primary and secondary school pupils. Yet they still find it difficult to apply their coping strategies. In practice, young people run into all kinds of barriers. Reporting functions are complicated or hard to find, social norms make it difficult to deviate from group behaviour, and they find time limits hard to maintain.”

Do you have tips for parents on how to deal with this better?

“Listen to your child and show genuine interest. From young people I hear that parents often respond angrily and punitively. I think that comes from fear or panic. I do understand parents banning things, it is often a reflex that comes from insecurity. But because of fear of punishment, and because they feel their parents do not understand at all what is going on in their lives, young people do not share their problems with their parents. Yet they really do need support. Acknowledge that your child has experienced something unpleasant or shocking, because that’s what makes a conversation possible. From that basis, you can look together at what is needed, whether that is support, filing a report or taking preventive measures. As parents, you really don’t need to know exactly how TikTok works to do this together.

“The home situation has a lot of influence on a child’s digital resilience. How do caregivers themselves relate to their social media? Does a child learn skills such as self-control and setting boundaries? Is there a warm home environment, or are there all kinds of other challenges going on that leave less room to support the child? Parents cannot always directly change that, but it does affect resilience.”

What is the responsibility of social media companies? Should those platforms moderate better?

“Most platforms already do a lot of moderation. But it differs greatly per platform and per user what you get to see. Complete filtering is also complicated, because content is uploaded by users themselves, sometimes with deliberately bad intentions, and can be cleverly ‘hidden’ so that algorithms just fail to recognise it.

“Still, more is possible than what is happening now. For film and television we have the viewing guide. By law, makers are required to classify their content with icons for violence, fear or sexuality, with clear age labels. There is such a thing as an online viewing guide. Large channels on YouTube fall under media law and are simply required to comply with that guide. But every uploader has to classify their own content, which makes it difficult. And there is no international coordination. You don’t only encounter Dutch content on YouTube, much comes from American creators. There is less legislation and regulation there. And of course you also want a level playing field for all those different platforms. That makes regulation difficult.”

What can the EU do in this?

“At the European level, legislation is being tightened that obliges platforms to better protect minors, for example through stricter requirements for age verification and regulating harmful content. The advantage of EU rules is that large platforms active in Europe have to comply, which also makes enforcement stronger than when countries try to do this individually. It does lead to backlash from tech companies, which demand a level playing field for all digital services. They argue that minors shouldn’t need age verification for social media, but can still freely access, for example, fireworks websites.”

It is scientifically difficult to label social media use firmly as ‘addictive’, like nicotine or alcohol

You are mild towards the platforms themselves. Yet it’s well known that social media companies design their platforms to keep users there as long as possible, rewarding content with strong, often negative emotions. Shouldn’t social media ensure by design that they’re less harmful and addictive?

“It is scientifically difficult to label social media use firmly as ‘addictive’, like nicotine or alcohol, where years of research have shown that link. But according to neuroscientists, we can still say something about addictive effects even without that kind of empirical evidence. We know how the brain works, and from that we can infer that certain design choices appeal to the emotional, associative part of the brain, making it hard to stop.

“I am sure there are people working at those platforms who strongly advocate for the interests of minors. At the same time, they are also commercial companies that want to make a profit. Many platforms are indeed designed around stimuli that automatically trigger behaviour and keep presenting something new, making it easy for users to stay on autopilot. I do see possibilities to design this differently. You could actively help users to pause, keep an overview of their time and, above all, give them more control over what they do and do not see.”

If you could redesign social media completely from scratch, what would the digital living environment look like?

“For me it is less about technical interventions, and more about how people interact with one another. Endless scrolling through positivity and warmth would have a very different effect from what we scroll through now. What we encounter online is a reflection of society. We don’t live in a world that is dominated by solidarity and kindness. I therefore mainly hope that technology develops in such a way that truly harmful and legally prohibited content, such as hate, grooming of minors or the unlawful distribution of images, is filtered out much better automatically. I hope users themselves gain more control over what they do and don’t want to see, just like in the analogue video world. If you want to watch an obscure horror film, that is fine for you, but it is not for me. Not everything needs to be locked down for everyone, but people should have much more freedom of choice and control, with room for the experiences and voices of young people themselves.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

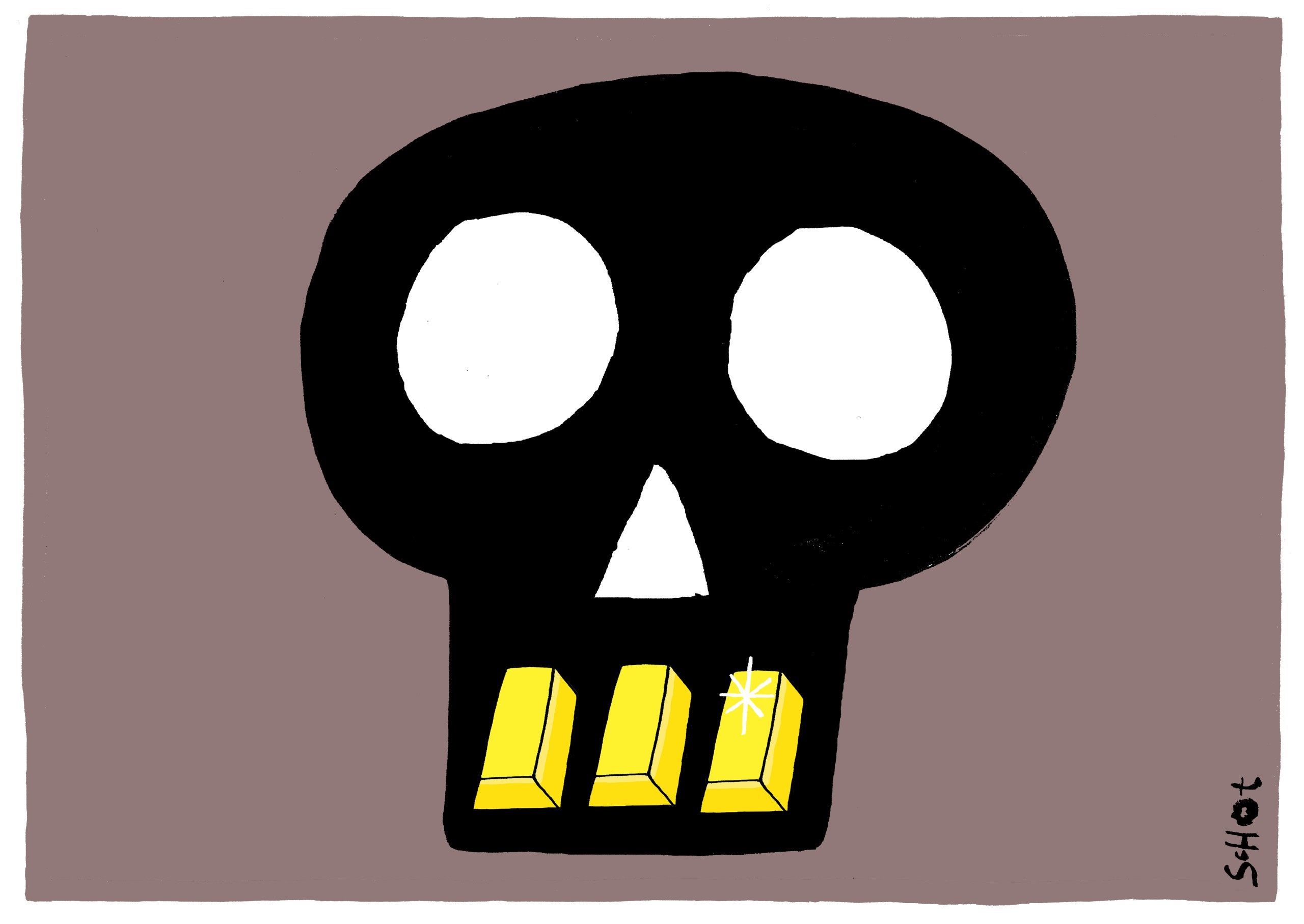

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

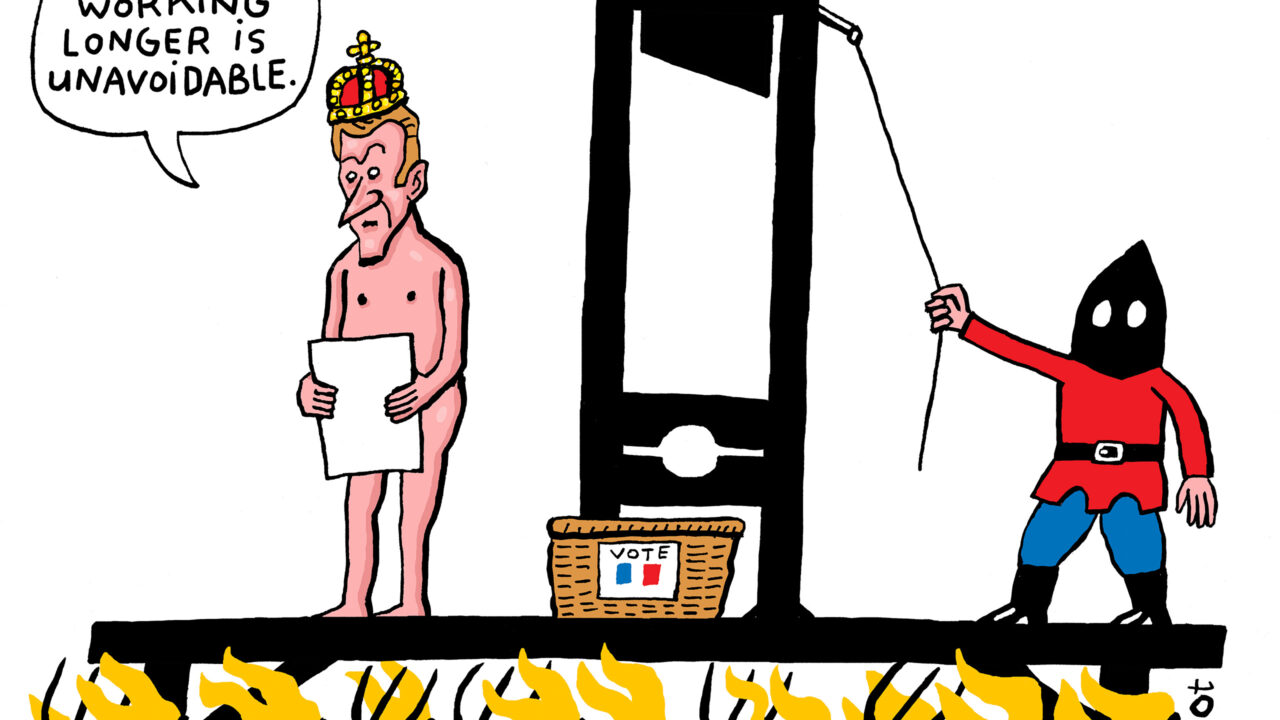

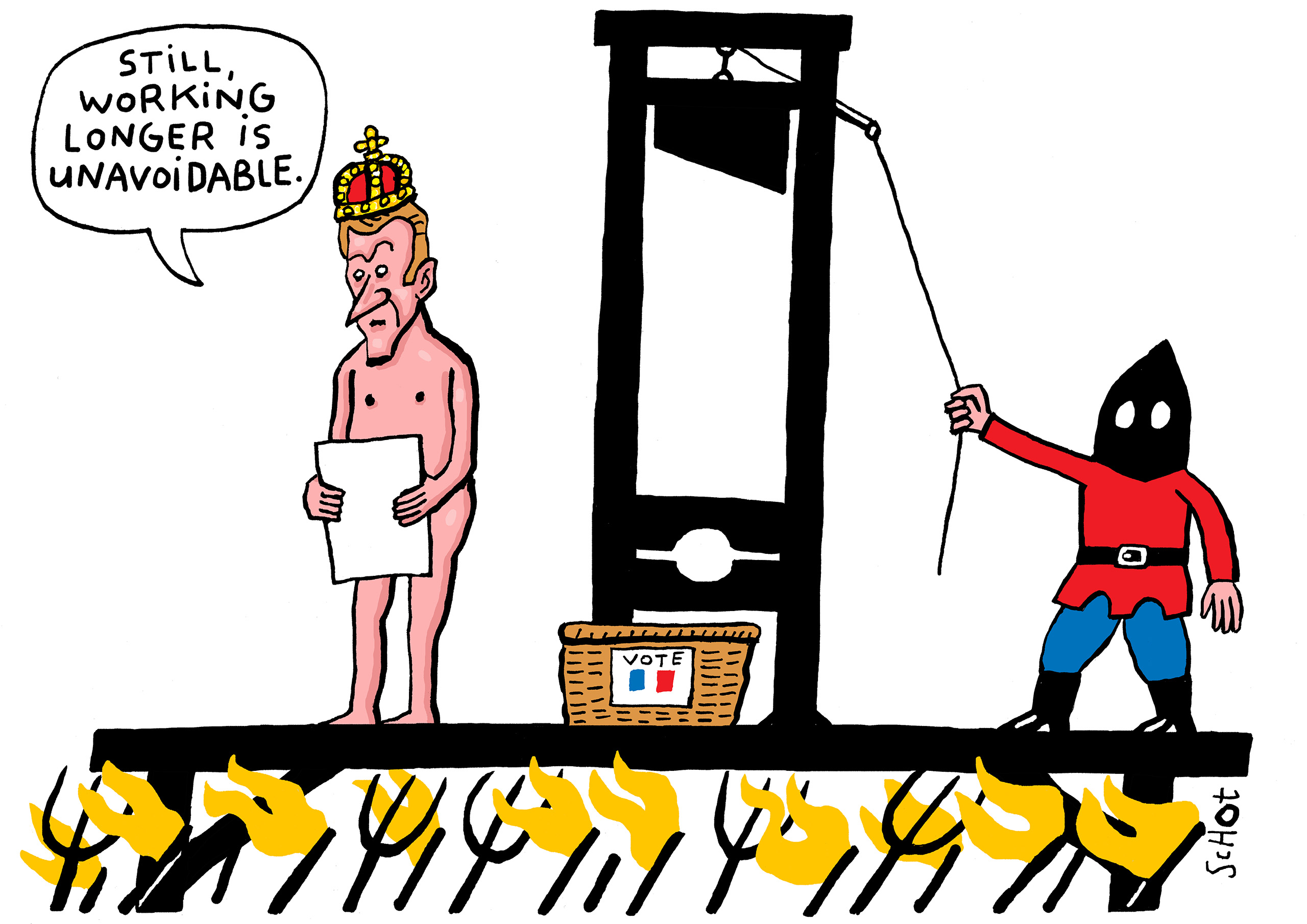

Why French politics is faltering under pension pressure

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-