Voters do make rational choices when they vote for populists, discovered Otto Swank

Trump voters would not be rational. Otto Swank did not believe it for a second. His search for a better explanation led to a mathematical model that reveals how even rational choices can result in unexpected election outcomes and the rise of contemporary populists.

Image by: Pien Düthmann

Eureka! Every scientist contributes a small amount to the sea of knowledge that humanity already possesses. It always starts with wonder, followed by research, discovery and results. In this series, scientists talk about their eureka moments.

The wonder

“With every election result, I was glued to the television as a child. I come from a CDA family, but my three older brothers thought very differently. There was a lot of talk about politics at home. That could be quite tense, those conversations sometimes ran high. And I already liked numbers back then. So that whole business of polls, voting, results and shifting seats immediately appealed to me.

“I have an enormous inner drive to understand how decisions within a democracy work. That became the thread in my research as a political economist. That fascination with voter behaviour was strongly rekindled during Trump’s first election. I heard economists saying that voters were crazy, and that really made me angry. It seemed highly unlikely to me that people would suddenly lose their minds en masse. There had to be a better explanation for why voters do what they do. That was the moment I dived back into voter behaviour.”

'I have an enormous inner drive to understand how decisions within a democracy work'

The research

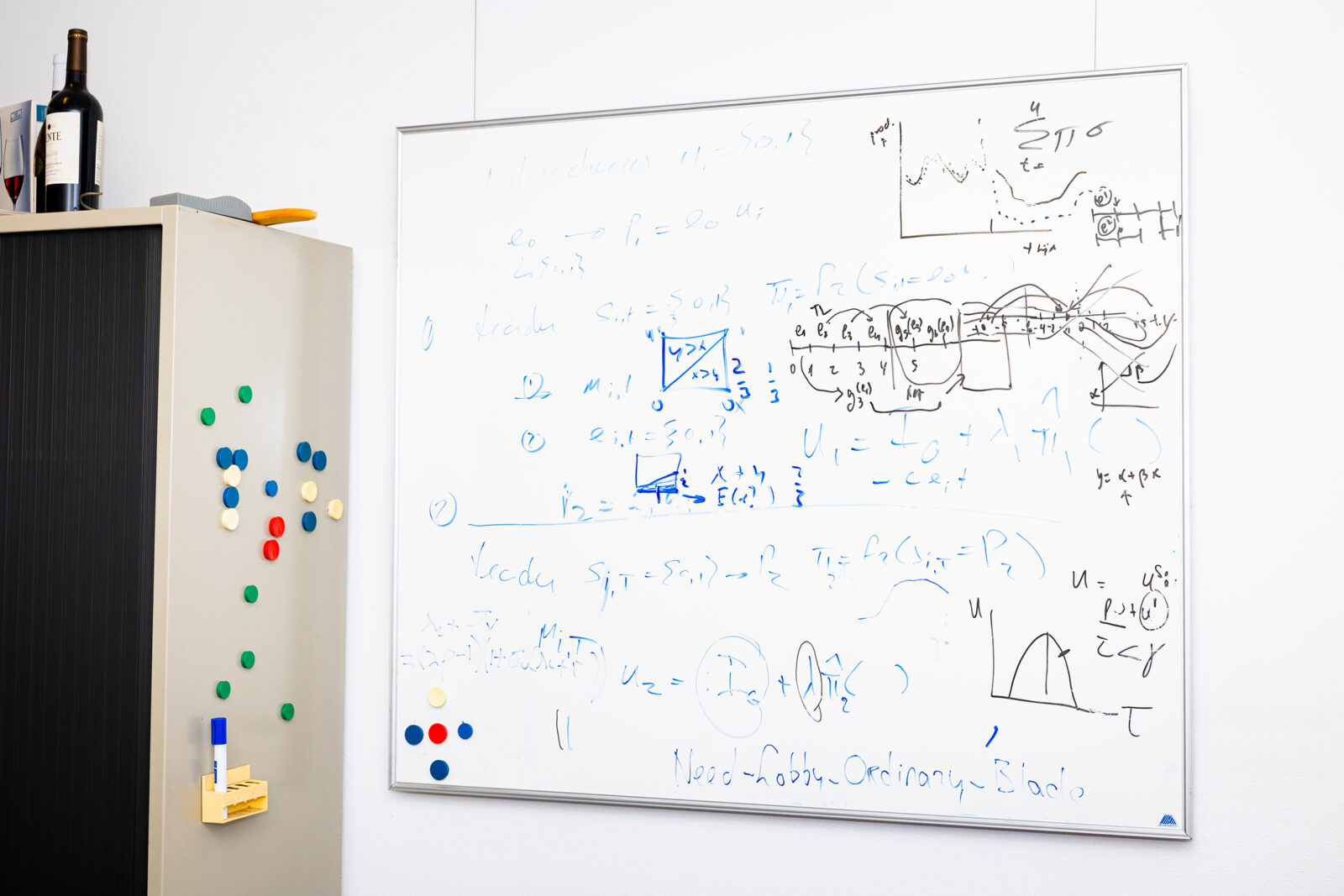

“Mainstream economic models then start from two things: what does someone want and what can someone do? That translates well to political behaviour. The first concerns someone’s preferences, and the second in this case concerns the information someone has, and whether it is correct or not. Together with Dana Sisak and Benoit Crutzen, I translated that into mathematical formulas, which we then combined in a model.

“In the model, we looked at two groups of voters: a small, well-informed group that knows what is in its interest, and a much larger group that only partially knows this. What is crucial is that the probability of receiving the right signal about what is good or bad for you differs between those groups. Suppose that part of that large group receives the wrong signal, so information that does not correspond with their interest, then they will vote for something that is actually not in their own interest. In this way, policies that are in fact beneficial to the elite, for example, can still receive a majority of the votes.”

Image by: Pien Düthmann

The eureka moment

“Calculating those votes was not even that complicated. But explaining why populists are gaining ground precisely now, that was difficult. Our model shows that this mechanism mainly plays a role with complex issues, such as globalisation, migration, economic insecurity. On these topics, less well-informed majority groups are less likely to receive the right signal.

“In recent years, there have therefore been election outcomes that served the interests of the elite. And that is precisely what creates space for populist politicians. It is difficult for traditional political parties to break with this, because they would then also have to attack the elite and policies they themselves have helped to create. Our model shows that it is precisely easier for political outsiders to successfully appeal to that group with more uncertainty.”

“During the research, I have the mathematics in my head, but getting it out is sometimes difficult. When the mathematics falls into place and aligns with the explanation of voter behaviour, and I realise that the model will become a paper, then adrenaline and other pleasant substances are released.”

Image by: Pien Düthmann

The aftermath

“The paper turned out to be quite controversial. One of the referees, a political scientist, even refused at a certain point to continue reviewing. That our model provided a rational explanation for why people vote for someone like Trump apparently went so strongly against his moral compass.

'I have come to realise that there is a large group of people for whom globalisation or migration is by no means self-evidently beneficial'

“My own perspective has also shifted. For me and my colleagues, globalisation is mainly pleasant: more good food, more diversity, cheap cleaners. I have come to realise that there is a large group of people for whom globalisation or migration is by no means self-evidently beneficial, for example because of more competition from cheap labour.

“At the London School of Economics, someone even teaches a class about the paper and calls it ‘the best explanation of populism’ he knows. That really is a compliment. I myself continue to develop the model. My follow-up research is about why migration is such a divisive issue. I look at how groups learn from each other what ‘acceptable’ voting behaviour is. Think of how in Germany after the war there was a strong norm against parties with xenophobia, and how that norm has nevertheless started to shift in the past ten years. I am trying to understand how such norms arise locally, how they spread, and how that becomes visible in voting behaviour.”

Otto Swank is professor of Political Economy at the Erasmus School of Economics and researches how information, uncertainty and institutions shape voter behaviour and policy choices. In his research, he connects economic game theory with current political questions, ranging from the rise of populism to the consequences of globalisation

De redactie

Comments

Read more in eureka!

-

Why legal scholars, philosophers and empirical researchers need each other

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

Why punishing or helping is not a right-versus-left story

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

How Jun Borras discovered that land grabbing is far from over

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

Leave a comment