A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Sudan is facing one of the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophes: nearly twelve million people have been displaced and almost half of the population is at risk of famine. Estimates of the total death toll range from 20,000 to 150,000. Associate professor in Development economics Elissaios Papyrakis explains how Sudan ended up in this spiral, who profits from it, and why a path to peace is impossible without massive humanitarian support.

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Elissaios Papyrakis is associate professor of Development economics at the International Institute of Social Studies. His research focuses on the political economy of natural resources, conflict, and development, with a particular emphasis on how mineral resource wealth shapes economic and institutional outcomes in Sudan and other parts of the Global South.

Why is there a war in Sudan?

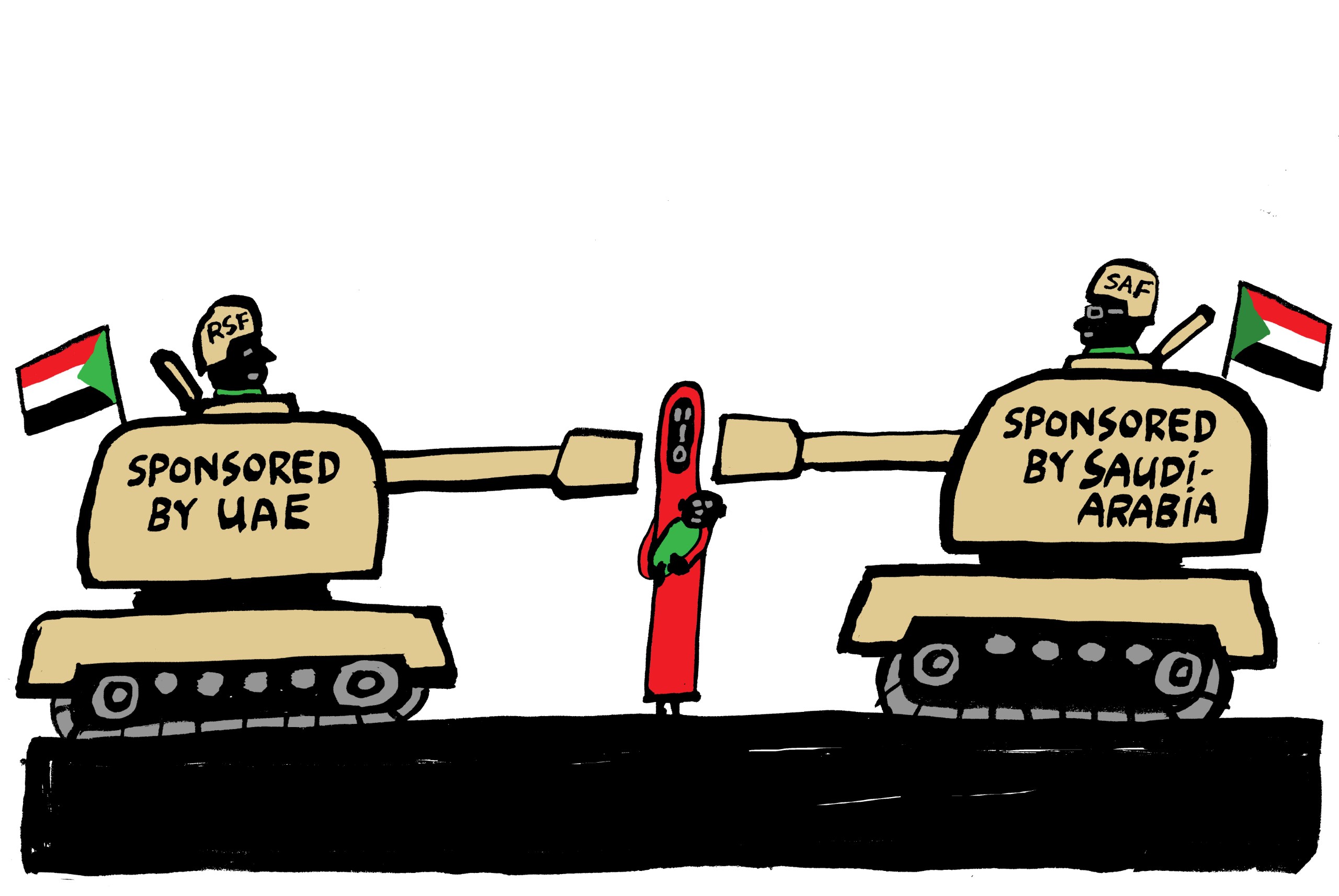

“The conflict has deep structural roots: competition over scarce natural resources such as land and water, long-standing ethnic divisions between Arab nomads and non-Arab farmers. Since 2023 these tensions have escalated into open civil war between two military factions: the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the internationally recognised military government, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary force. Both groups are fighting for military control and economic dominance.

“This war cannot be understood without looking back at Darfur in 2003. The then-president Omar al-Bashir, belonging to the Arab majority, supported and armed a militia force called the Janjaweed. Both al-Bashir and the Janjaweed were involved in committing the genocide against non-Arab communities in 2003. In 2013, al-Bashir rebranded the Janjaweed into the Rapid Support Force, which operated in parallel to the official army.

“In 2019 there were large scale protests driven by anger over economic hardship, and both the army and the RSF turned on al-Bashir. After al-Bashir was removed from power, power was supposed to be shared between civilian representatives and the military, consisting of both the SAF and the RSF. However, in 2021 the military forces committed a coup and abandoned the power sharing deal with the civilian representatives. The SAF and RSF jointly took power, but it proved an ‘unhappy marriage’ as a power struggle developed between the RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan ‘Hemedti’, and the SAF commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

“In 2023 the RSF attempted to seize power. Initially the group took control over the capital Khartoum, and large parts of Darfur and regions in the east. The latter is still under their control, while the SAF regained control over Khartoum and the economically vital Nile corridor. The result is a military and political deadlock: each side is gaining ground in different regions, neither willing to negotiate, and leaving civilians trapped in a protracted and devastating conflict.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

How do resources play a role in this war?

“Before 2011, oil accounted for the bulk of Sudan’s export revenues. Sudan didn’t prove immune to the so-called ‘resource curse’. This curse predicts that countries that rely too much on depletable mineral resources will run into trouble, like developing weaker political and economic institutions, higher levels of corruption, limited political stability, excessive bureaucracy, and lack of economic diversification.

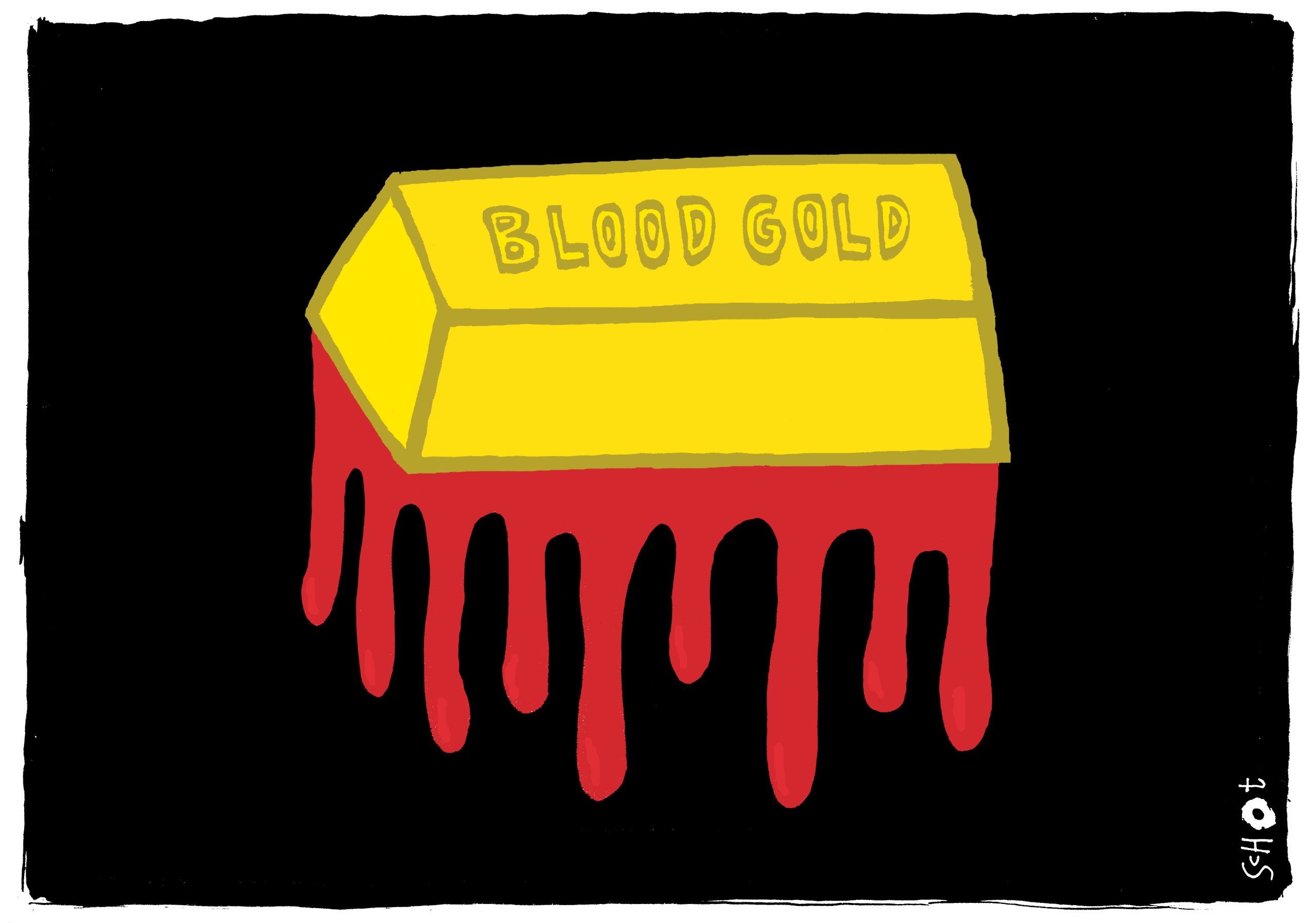

“When South Sudan seceded in 2011, Sudan lost almost 80 per cent of its oil reserves. Ever since, Sudan relied mostly on extracting gold. In 2019, so before the civil war when reporting of economic data was more reliable, gold accounted for roughly 75 per cent of export value. So once again, Sudan became extremely dependent on a single, lootable resource.

“This dependency on a single resource, together with ethnic divisions, can lead to what in conflict studies is known as the ‘greed-grievance’ dynamic. In Darfur, Arab nomadic groups and non-Arab farming communities have long competed over land and water, and political power has historically been monopolised by the Arab majority. Gold revenues are not distributed equitably, and the non-Arab farmers do not benefit, whereas many of the mines are located on the land where they live.”

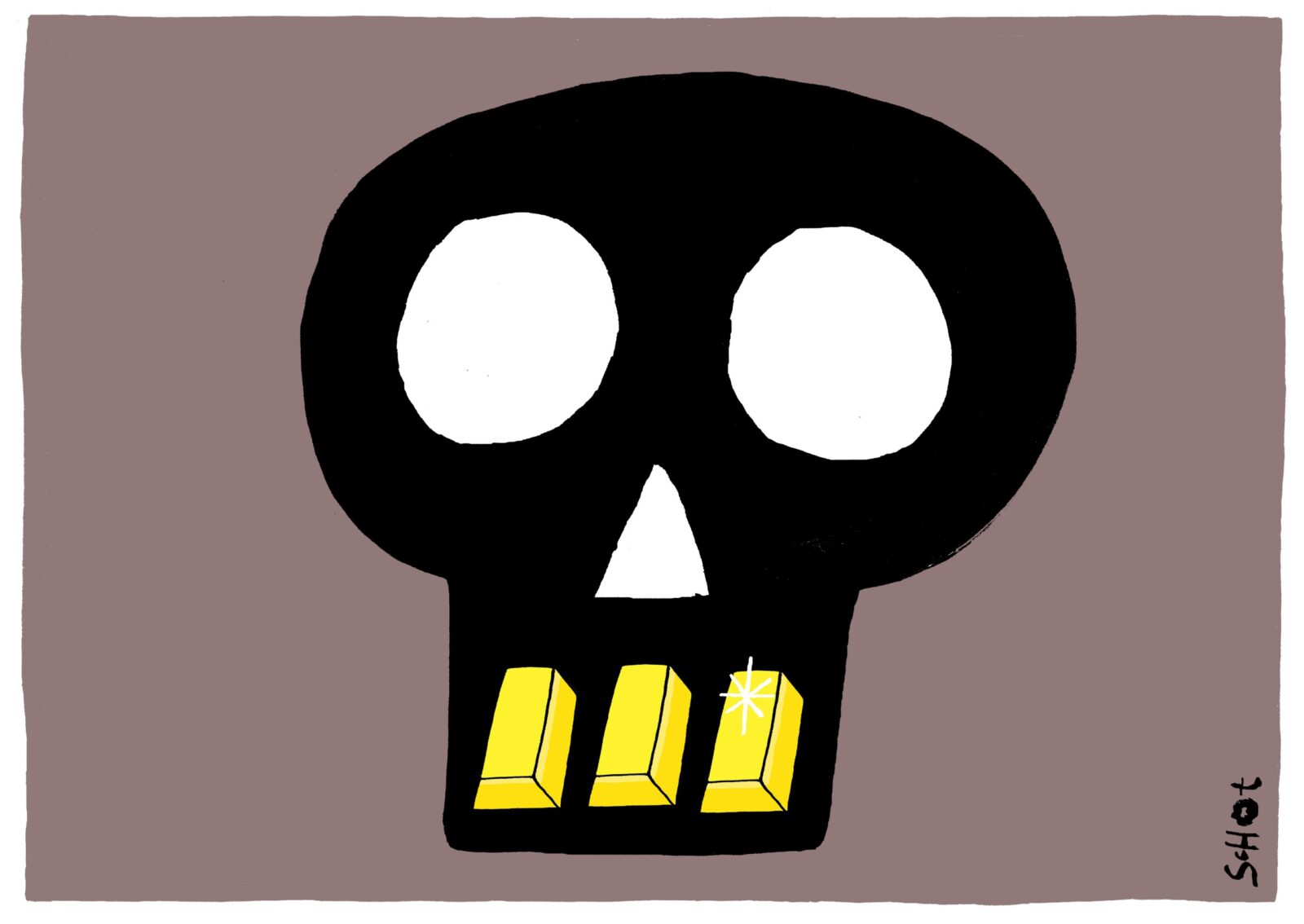

Who controls Sudan’s gold mines, and how does this affect the course of the war?

“Control over Sudan’s gold deposits is effectively split between the two warring factions, and that division fuels the conflict. The RSF holds most of Darfur, where a large cluster of gold mines lies, while the SAF controls the northeastern region, another area rich in deposits. Almost all other economic activity has collapsed: agriculture is disrupted, the little manufacturing the country had is stalled. So gold has become the country’s lifeline.

“The SAF can use officially exported gold to generate revenue. But because the RSF is not internationally recognised, it relies on informal extraction and smuggling. The mines in the Darfur region lend themselves well to informal, or ‘artisanal mining’. There are many smaller mines, in remote areas, where artisanal miners operate. The RSF cooperates with these miners to secure a steady stream of cash by selling the gold abroad. That money pays soldiers and buys weapons. This is what makes this conflict a ‘self-funding’ war: as long as both groups control gold-rich territory, they can simply extract more whenever they need resources, which removes any economic incentive to de-escalate.”

‘They can simply extract more whenever they need resources, which removes any economic incentive to de-escalate’

Is it too simplistic to think that regulating the gold trade could end the conflict?

“From a resource-conflict perspective, the current situation in Sudan resembles the conflicts in West and Central Africa of some thirty years ago. These conflicts were financed with ‘blood diamonds’, and diamond smuggling. An international certification system certainly helped to make the trade more transparent. Such certification doesn’t exist for gold. Once it’s sold, you can melt it, and afterwards it’s impossible to trace its origin.

“So in theory, a certification scheme for Sudanese gold could certainly help end this conflict. But neither the SAF nor the RSF has any incentive to support such oversight, as they both rely on gold revenues to sustain their military operations. Only if Sudan transitions to a civilian, democratically elected government would there be political space for change. And even then, it would require broad international coordination, especially from major buying countries. That will be more difficult than it was for diamonds. Diamond production is concentrated in relatively few places, but gold is mined in far more countries and in more informal ways. There already exists a transparency framework for gold and mining activity: the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. It would be great if Sudan could join once the war ends. And even then, the dominance of artisanal mining makes monitoring extremely difficult.”

Who buys Sudanese gold?

“Several media reports suggest that the United Arab Emirates may be involved involved in supply chains that include smuggled Sudanese gold. However, there is no definitive evidence for this yet. Before the conflict started in 2023, when we still had official documentation, the United Arab Emirates was Sudan’s most important gold importer. They import the gold, refine and export it, so they have a strong economic stake in keeping those supply lines open. Many reports state that the UAE side with the RSF and help them with logistical support and even weapons. The United Arab Emirates officially reject that this is true, but it’s widely reported in the media.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Which other international actors are involved in this conflict?

“Saudi Arabia is the other key regional player, and it backs the SAF. That fits a long-standing geopolitical rivalry with the UAE: both countries compete for influence, access to trade routes, mining concessions and political leverage around the Red Sea. The SAF historically maintained strong ties with both Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Also in this light, as the UAE and Saudi Arabia compete for influence, it is not surprising that the UAE opportunistically sided with the RSF.

“As a neighbouring country, Egypt’s interests are twofold: the Nile flows through Sudan, so stability is crucial for water security, and Egypt currently hosts more than a million Sudanese refugees. That puts real pressure on its economy, so Cairo has incentive to push for de-escalation, and backs the officially recognised government, the SAF.”

‘A durable peace ultimately requires economic and political compensation and political involvement after the transition’

What role can the international community play in resolving the Sudanese conflict?

“Sometimes the international actors that are part of the problem, are also part of the solution. The US, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates proposed a peace plan in September. It calls for a ceasefire, renewed access for humanitarian aid, and ultimately a transition to a civilian-led government. But mistrust between SAF and RSF runs deep. Both fear that any truce will simply give the other side time to regroup. Moreover, a transition to a civilian government would strip both of them of political and economic power. In that sense, they have no incentive to end this conflict. So a durable peace ultimately requires economic and political compensation and political involvement after the transition.”

What could Western governments and institutions like the UN do to alleviate the crisis in Sudan?

“The single most urgent need is humanitarian aid on a scale that Western governments have so far failed to deliver. After Sudan transitions to a civilian government, a large humanitarian aid package needs to be in place. However, major donors, including the US and the Netherlands, have recently cut their aid budgets. Aid is absolutely crucial, from a humanitarian perspective, and for sustainable, peaceful nation-building, as the country will need to be rebuilt from scratch.

“After the cease-fire, I would be surprised if there are not some peace-building forces needed to maintain political stability and the peace process. That could be the UN, but the African Union could also take that role as they might be received more favourably.”

I hear you see plenty of opportunities for Sudan to lift itself out of its situation after a ceasefire and a transition to a civilian government. But how likely is it that Sudan reaches that point any time soon?

“It’s a humanitarian crisis of immense dimensions, such a violation of human rights, so much violence, so many displaced people and there is a massive pending famine. The situation is so dire that the international community cannot look away much longer. In that sense I’m optimistic that international pressure and engagement will increase.”

Do you find that an optimistic insight?

“Well, I do see some things changing in the last few months. There has been more attention for the conflict in the media. And you can think of Trump what you want, but the fact that he positions himself as a peacemaker seems to help. He somehow manages to put a lot of pressure on people to lay down their arms. In the recent months he’s been getting more involved, so let’s see what that brings.”

Read more

-

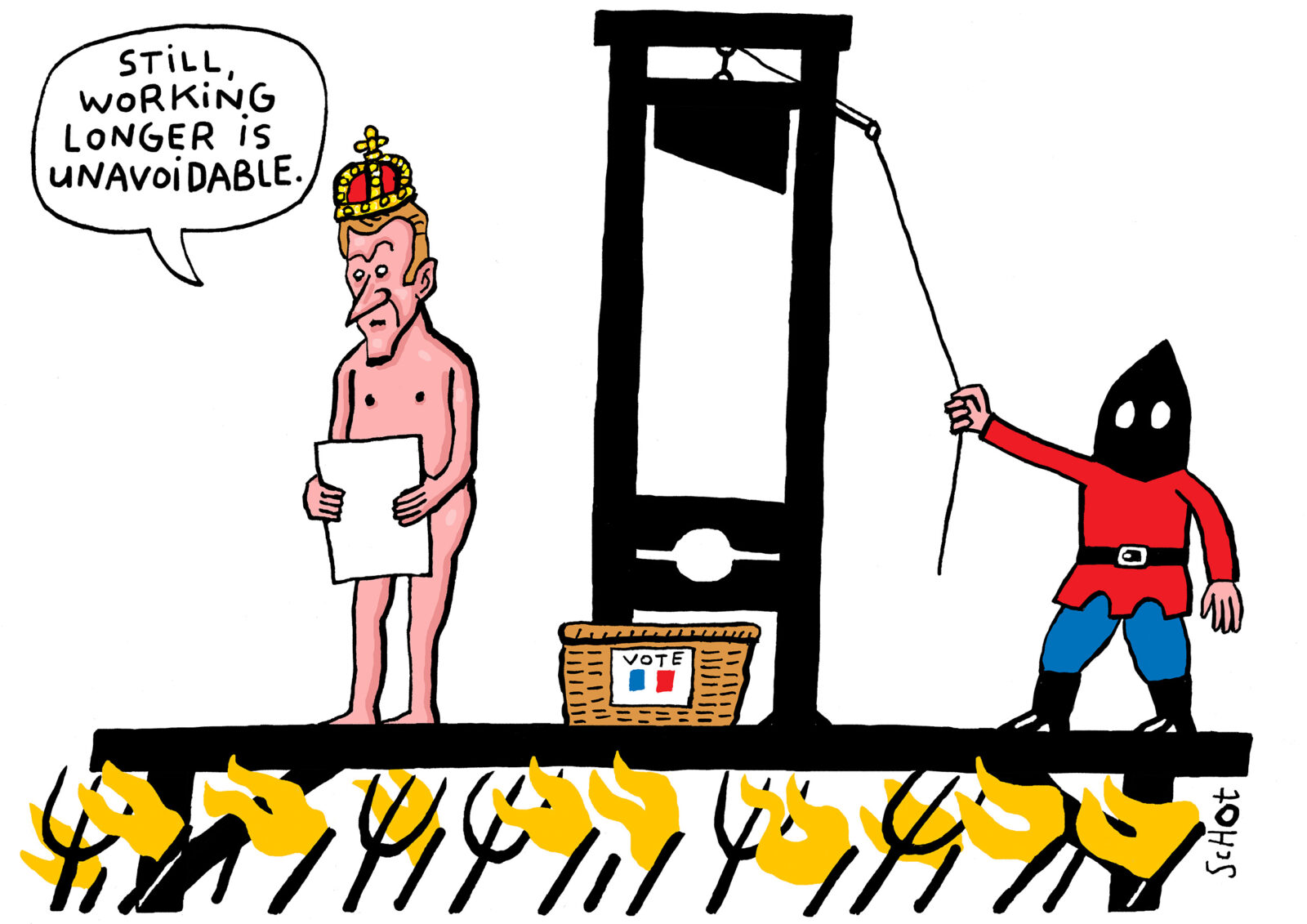

Why French politics is faltering under pension pressure

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

De redactie

Latest news

-

Why facts are orange and opinions purple on EM’s new website

Gepubliceerd op:-

Editorial

-

-

Shivering or sweating in Sanders: staff sat in the office with electric blankets

Gepubliceerd op:-

Campus

-

-

Great unexpectations

Gepubliceerd op:-

Column

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

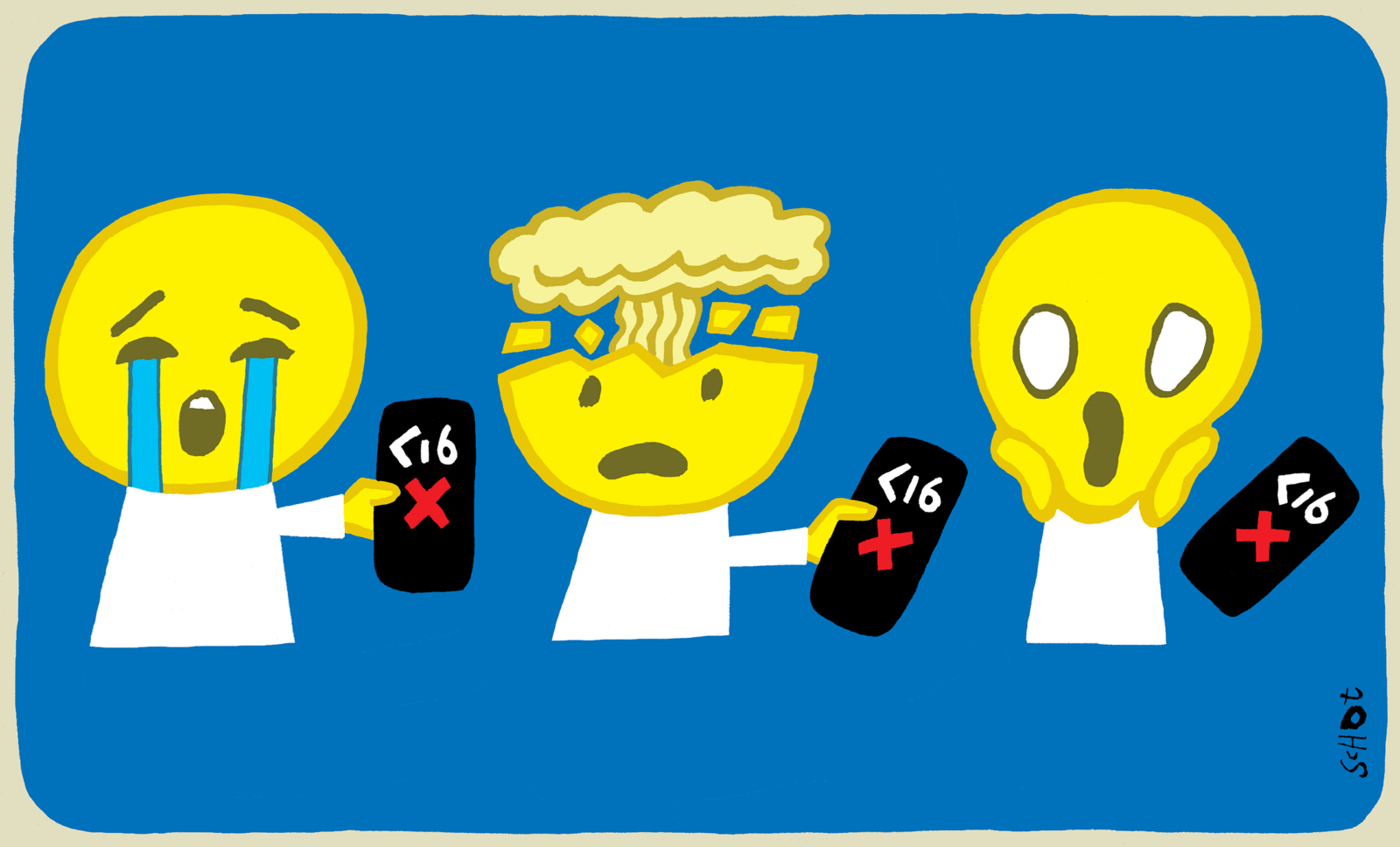

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

Why French politics is faltering under pension pressure

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

‘Artists like Bob Vylan and Kneecap are more than just a mirror of society’

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-