A fellow student as a doctor’s assistant: ‘With an STI, I would not dare go to the GP’

For many people, calling the GP is already nerve-racking. For some Rotterdam students, that threshold is even higher, because the assistant on the phone might be a fellow student, housemate or friend. That leads not only to discomfort but also to mistrust: what if that familiar face looks into your file or talks about you during a break?

Image by: Eva Gombár-Krishnan

When Evi (not her real name*) moved to Rotterdam three years ago to study Medicine, she registered with a Rotterdam GP practice. “It seemed practical to have a GP in my student city. I had heard about a practice without a waiting list that mainly focused on students”, Evi says. “I did not know then that medical students also worked there.”

‘How is your hand?’

She only found out months later. After a night out, she fell off her bike together with a friend and hurt her hand. “At first, I did not think much of it, but when it was still blue and painful after a few days, I decided to call the GP. Luckily it was not too bad: nothing was broken.”

Afterwards she discovered that the staff member she had spoken to on the phone was someone she knew. “I was sitting with friends in the Education Centre when someone called out in the corridor: ‘How is your hand now?’ It turned out to be the staff member from my GP practice. He said it so loudly that everyone could hear it. I was shocked. Personal information like that should remain confidential.”

Postponing GP visits

Until that day, Evi had never considered that acquaintances might be working at her GP surgery, but now the experience is often on her mind. “Since then, I have gone to my GP less often”, she says. These days the first contact goes through an app with a chat function, but only after submitting your complaint do you see who is helping you, meaning you can no longer ask for another staff member. “That really makes me more hesitant to go to the GP. Nine times out of ten I get the same boy as with my hand, and that does not feel comfortable.”

Evi would like to switch GP, but that turns out to be difficult. “Patients without a GP get priority. If I want to switch, I end up on an endless waiting list.”

Many medical students in Rotterdam end up at the same GP practice, where they can be both patient and staff member. That is because few GPs take on new patients directly or specifically focus on students. This can lead to tricky situations: students encounter each other at vulnerable moments and worry about their privacy.

Some, including Evi, therefore postpone their GP visits, which brings health risks. Anyone, for instance, who continues walking around with symptoms of an STI or scabies risks spreading the condition further or making the symptoms worse. For other sensitive topics, such as mental health problems, postponing a GP visit can also lead to more serious complaints.

Popular side job

A job as a doctor’s assistant is popular among Rotterdam medical students. The vacancy page of MFVR, the faculty association for medical students, is full of vacancies. At the moment there are twelve vacancies for GP assistant. Recruitment is also widespread in group chats: in August alone four vacancies were circulating. GPs across the city are looking for assistants, from the Oude Westen to Zuidplein. Due to the acute staff shortage, many practices cleverly make use of the fact that Erasmus University has a medical faculty.

Students can apply from their second year, but the job is particularly sought-after during the waiting period for clinical internships. For many it is also very educational. “I did it between my bachelor’s and my master’s”, says master’s student Daphne. “You see all sorts of things, you learn a lot and your medical knowledge stays up to date. It is very helpful for my clinical rotations now.”

‘With an STI or a sexual problem I would never dare go to my GP’

Higher threshold

Still, there is a downside to this setup. At Erasmus MC stories circulate about awkward situations. That raises the threshold to go to the GP, says medical student Danicz. “I often recognise the names of the people who help me. That makes it much harder to come in with embarrassing problems”, she says. “With an STI or a sexual problem I would never dare go to my GP. And I do not think I am the only one. People might walk around with complaints for longer, and that can be dangerous. I also notice that for that reason I am less quick to contact the GP. The risk of getting a familiar person on the line holds me back.”

The fear that acquaintances have access to medical records further raises the threshold to seek help, according to a survey by EM of fourteen medical students. According to Evi, this is especially problematic in the student world: “In the Medicine bubble almost everyone knows each other. In my group of friends, we often talk about this issue, and it sometimes makes me feel that my medical data is not entirely safe. I might worry that students’ medical data are gossiped about during breaks, or that records are accessed without reason.”

Gossiping

Hannah (not her real name*), a medical student who works at the practice where Evi is a patient, understands those concerns well. “It happens quite often that colleagues know their own patients. Sometimes that is also discussed among us. You might say: ‘I had this person on the phone today’, and sometimes the reason for the visit is mentioned as well.”

Juliette (not her real name*) worked at the same GP practice for three years and can also relate to patients’ concerns. “I would never want to be a patient at this practice myself, but I do think that medical students are very aware that sharing medical information is forbidden, and that they stick to that.”

Still, she admits there is always a risk. “When I had just started working there, I heard that someone had been dismissed because he told members of his student association that one member had an STI. When that came out, he was dismissed immediately.” According to Juliette, no similar incident occurred in the three years after that.

Treating someone you know

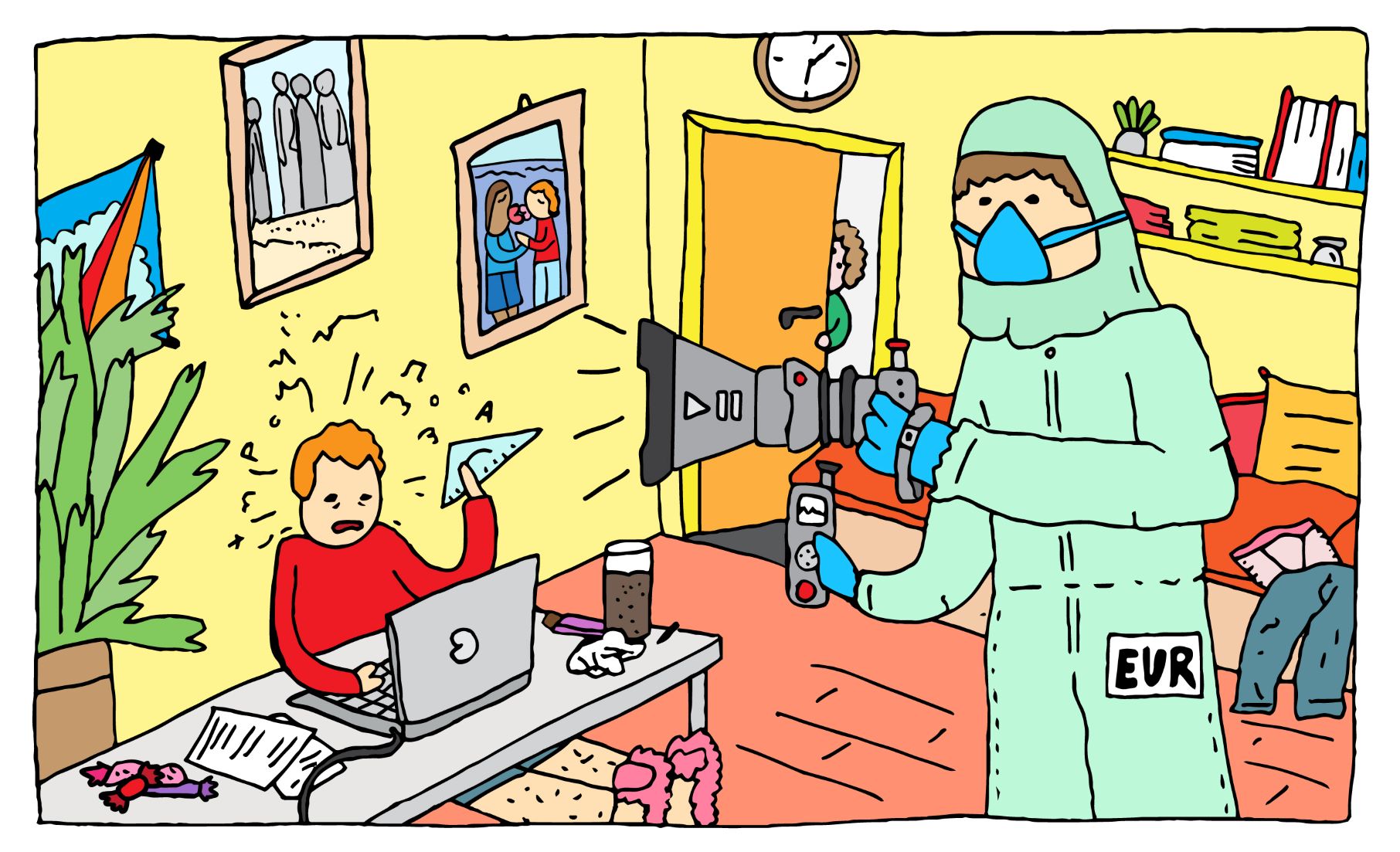

Image by: Eva Gombár-Krishnan

Hannah and Juliette have themselves had to help students they personally knew. “Luckily it was something harmless, but I know colleagues who were asked questions about STIs or contraception by fellow students they knew personally”, Hannah says. “In such cases you can transfer the patient to another staff member, but there are no clear guidelines for this. All they say is: ‘Stay professional.’”

Besides being unpleasant for patients, Hannah points out that it can also be uncomfortable for staff to have someone they know as a patient. “There are things I would rather not know or see about my fellow students. Doctors sometimes ask patients to send photos of genitals, stools or discharge. Those images then have to be uploaded via a chat function. Neither the staff member nor the patient knows in advance who they will be matched with. That can lead to very awkward situations.” Juliette confirms this. “It is awkward to see that person again afterwards.”

Professional secrecy

To prevent misuse, all staff in a GP practice are bound by confidentiality and professional secrecy. In addition, GPs regularly carry out random checks to detect unlawful access to medical records, on the recommendation of the Dutch Data Protection Authority. Anyone who fails to do this risks a fine.

Discussing patient cases with fellow students is only allowed if it benefits the treatment, stresses Eline Bunnik, associate professor of medical ethics in the Department of Public Health at Erasmus MC. “The same applies to accessing records. That is only permitted when you are directly involved in the treatment, never out of curiosity.”

Protecting privacy

According to her, these rules should be self-evident for medical students. “The degree programme pays extensive attention to ethical standards such as confidentiality and professional secrecy. The responsibility therefore lies with the student first”, Bunnik says. Still, she believes practices could do more to protect patients’ privacy. “It is wise to remind new staff of the rules and to discuss as a team regularly how to handle privacy carefully.”

That does not mean you must never share anything, Bunnik nuances. “Some exceptional or impactful cases create the need to talk about them with colleagues. That is understandable, and important for learning from such cases, but be cautious and never share more information than strictly necessary. Always ask yourself: does this benefit the quality of care? Mentioning a name, for example, is not needed.”

Do not treat acquaintances

Bunnik refers to the code of conduct of the KNMG, which offers doctors guidance in situations where a personal relationship with a patient may affect the quality of care. She believes that those guidelines can also apply to medical students. The code of conduct states that doctors should in principle not treat friends or family members.

“A code of conduct functions as a professional standard: a shared agreement among doctors about what good practice entails”, Bunnik explains. “Disciplinary boards also use such standards to assess what counts as ‘good care’. There are always exceptions, for example in emergencies, but the rule is clear: do not treat people you know well personally.”

Still, Bunnik acknowledges that it is often not black and white. “Students must assess for themselves whether their relationship with a patient may affect the quality of care.”

Jans Huisartsen

One of the most popular GP practices among Rotterdam students is Jans Huisartsen. The practice focuses specifically on students and now has three locations in the city. Dozens of medical students work there alongside their studies, meaning that it often happens that patient and staff member already know each other.

According to founder and practice manager Luc Jansen, students need not worry about their privacy at his practice. “Confidentiality always comes first for us”, he writes in an email. “All staff sign a confidentiality agreement and comply with their professional secrecy. We also carry out random checks to prevent unauthorised access to patient data.”

*The names of Evi, Hannah and Juliette have been changed for privacy reasons. Evi because she shares medical information, Hannah and Juliette because they fear possible consequences at work. Their real names are known to the editors.

Read more

-

New medical practice near the campus hopes to be the answer to students’ GP problem

Gepubliceerd op:-

Campus

-

De redactie

-

Sarah de Gruijter

Sarah de GruijterStudent editor

Latest news

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

-

Company takes a huge chunk of the student finance of at least 350 internationals

Gepubliceerd op:-

Internationalisation

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in Privacy

-

TU Delft admits error in sharing names of activists

Gepubliceerd op:-

Privacy

-

-

Board wants fewer proctored exams, but ‘we do have to safeguard the quality of our exams’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Privacy

-

-

Hundreds of EUR students protest two-camera set-up in online exams

Gepubliceerd op:-

Privacy

-