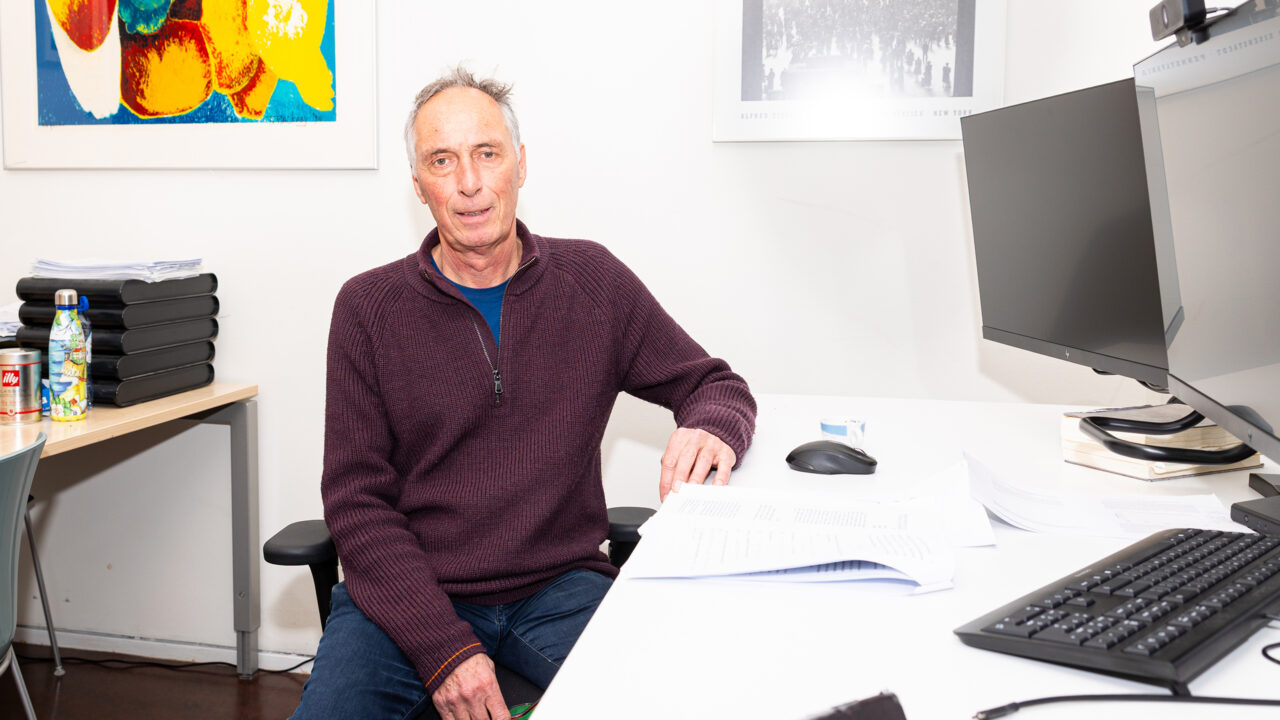

Why the same brain area prompts adolescents to recklessness and to social bonding

Why do young people sometimes behave recklessly, yet moments later be very social and caring? Eveline Crone discovered that during puberty the brain is not only susceptible to excitement and risks, but also particularly sensitive to friendship and cooperation.

Image by: Esther Dijkstra

The wonder

“Teenagers have a bad reputation: lazy, selfish, not listening, but I see adolescence as a hopeful period in which young people broaden their world, make friendships and wonder how society works and how it can be improved. What intrigues me is that they are full of contradictions: sometimes they use their prefrontal cortex very well for planning and impulse control, and sometimes not at all. I suspected that emotions play a key role in this. I had already researched emotions during my doctoral research. But at the time emotions were often dismissed as noise.”

Eveline Crone is professor of Developmental Neuroscience in Society at the ESSB, and she is lead researcher at the Erasmus SYNC Lab. She studies how the adolescent brain develops and the role emotions and social relationships play in that.

“At the start of my career colleagues said: ‘Don’t do research about adolescence, that’s always messy.’ I found that a fun challenge. And I saw many opportunities with neurological research. That was uncharted territory, especially within developmental psychology.

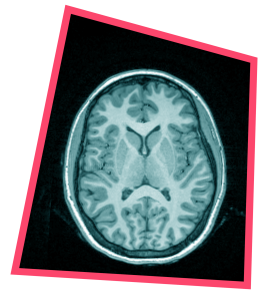

“The brain I find truly magical. It’s a bit like the universe. On the one hand very ordinary, everyone has one, and on the other hand very complex and unfathomable. How all the neurons work together is something we still understand very little about.”

The research

Image by: Esther Dijkstra

“During my studies in Pittsburgh I learned how to map brain activity with fMRI while someone performs a task. Back in the Netherlands I set up a lab to investigate how young people’s risk behaviour is related to emotions. In adults it was already known that emotion centres play a role, and I wanted to see how those rational and emotional brain regions work together in the adolescent brain. In 2005 I started my first experiments. Through lectures in which I talked about my book The adolescent brain, so many enthusiastic parents and young people signed up that I had more participants than I could include.

“The first experiment was a card game, in which young people aged 10 to 25 had to guess whether the next card would be higher or lower than the turned-over card. We linked small amounts of money to the bet. And we introduced social elements: what if they were not gambling for themselves, but for their friends or parents?

“Using fMRI we looked at what happens in the brain as the risk in the gambling game increased and the person was right or wrong. We studied various emotion centres, with a leading role for the ventral striatum. That is an emotion centre that responds to stimuli from risky behaviour. Those brain regions are often seen as the main reason young people start vaping, drinking alcohol or breaking the rules.”

The eureka moment

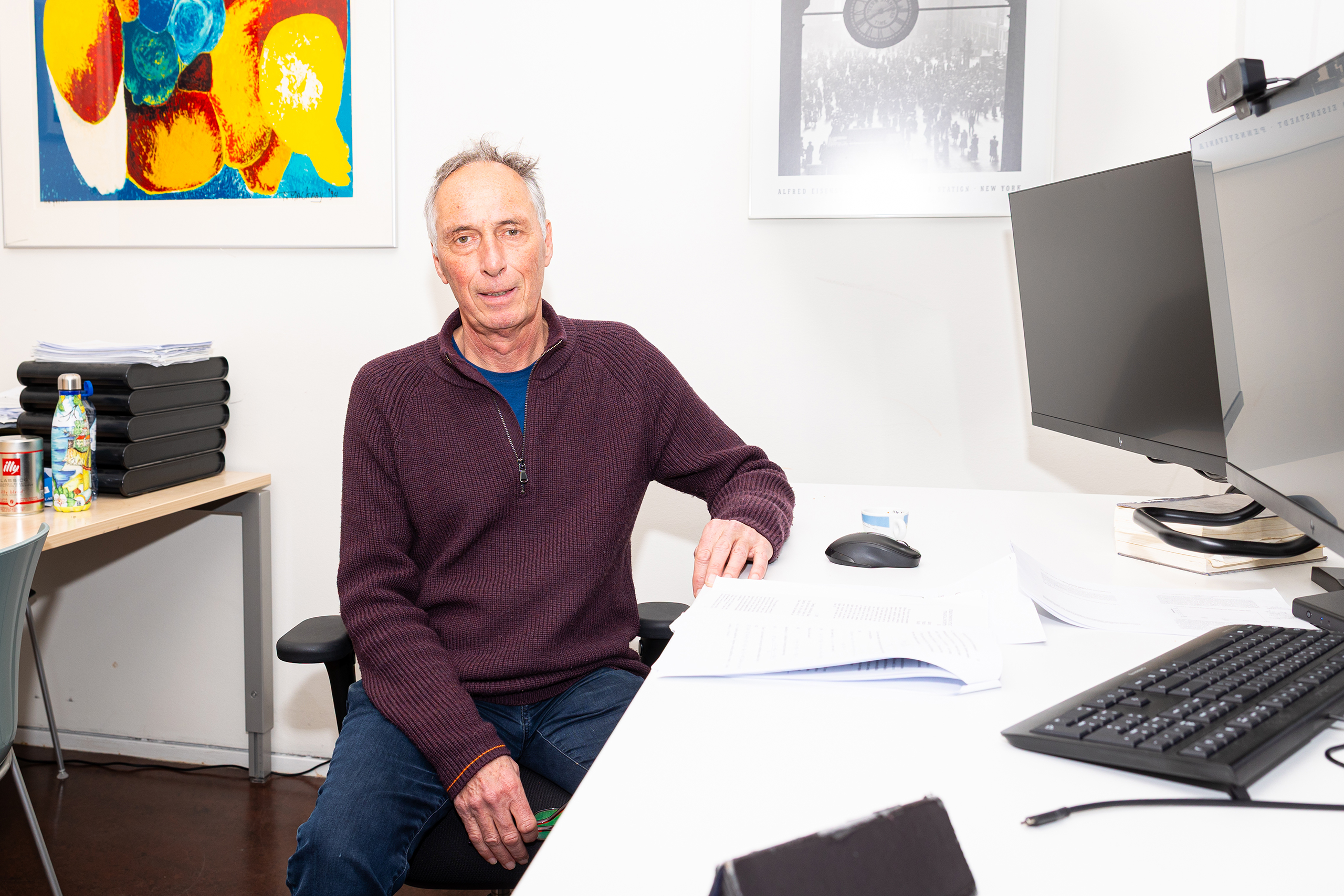

“We discovered that exactly the same brain systems were active when young people played the gambling game for themselves, for friends or for their parents. The area we had always thought explained ‘bad’ teenage behaviour therefore also turned out to be important for positive social behaviour. I really thought: ‘Wow, this turns the whole field of adolescent psychology on its head.’”

The aftermath

“The results led to a new direction in developmental psychology in which social influences on brain responses came to the fore. My findings raised many new questions, which both other scientists and I have investigated further. For example, I later discovered that the effect reversed when young people played the game for someone they found unfair or unpleasant: there was then more reward activity when that person lost; a form of schadenfreude.

Image by: Esther Dijkstra

“Teenagers often have a bad reputation, but our findings showed that there is an evolutionary advantage to their brains being highly sensitive to rewards in this phase. That provides greater understanding of young people’s behaviour and their inner world.

“It also brought a theoretical shift. Moral dilemmas were long seen as rational calculations of right and wrong. Emotions were regarded as noise. At the time, adolescent psychology was stuck in the metaphor of the brain as a computer, and our brain research created a break with that.”

Read more

-

How an algorithm tames chaos on the railway

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

De redactie

-

Manon Dillen

Manon DillenEditor

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in Eureka!

-

Why the economy doesn’t belong to economists

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

Voters do make rational choices when they vote for populists, discovered Otto Swank

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-

-

Why legal scholars, philosophers and empirical researchers need each other

Gepubliceerd op:-

Eureka!

-