How the Dutch self-image maintains supremacy

The Netherlands sees itself as moderate, rational and civilised – but that persistent self-image actually stands in the way of true democracy, says Dutch-language scholar Saskia Pieterse. “The current migration policy is not reasonable governance. It’s performative cruelty.”

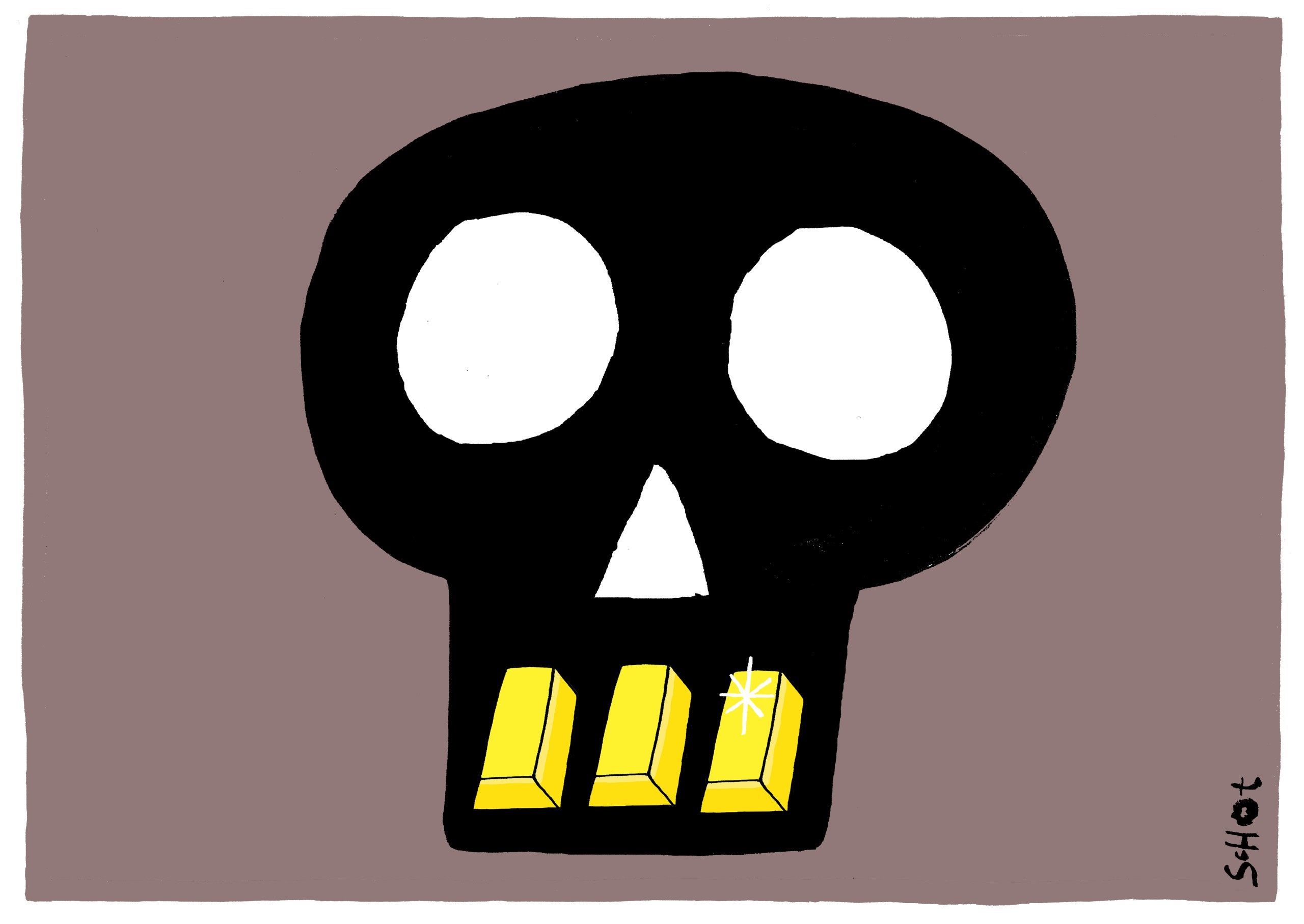

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Saskia Pieterse has been endowed professor of Literature and Society at the Erasmus School of Philosophy since September 2024. In her research, she focuses on the knock-on effects of the colonial past in Dutch history. Together with theologian Janneke Stegeman, she wrote the recently published book Uitverkoren: over hoe Nederland aan zijn zelfbeeld komt (The chosen people: how the Netherlands got its self-image).

What is the Dutch self-image?

“A chronically positive one. We see ourselves as pragmatic, non-ideological, averse to extremes, rational and always willing and able to consult. The Dutch are autonomous, free people, but also know how to deal with their freedom responsibly. We prefer trade to principles. That may not be the highest moral ideal, but it helps to avoid tipping into extremes. This enables us invariably to position ourselves in the rational middle.”

To what extent is that image correct?

“Some issues are hardly ever talked about, like Dutch colonialism. The establishment and continuation of colonialism went hand in hand with excessive violence. To justify that violence, you need a sense of superiority. This requires a political and moral order: white Protestants were given many privileges, other groups were given fewer, and they were pitted against each other.

“Our whole history of supremacy and racialisation doesn’t fit into the narrative of moderation and good governance at all. That’s because supremacy remains somewhat underexposed in the narrative we proclaim about ourselves. ‘Yes, the Netherlands did these things’, people will say, ‘but it was a long time ago, and far away, overseas. Besides, it was something all the superpowers were doing at the time.’ That’s a convenient way to prevent it from weighing on our self-image.”

Where does that image come from?

“From the Calvinist statesmen who shaped the Dutch Republic. Protestants saw themselves as the chosen people. ‘Chosen’ is a Biblical term; in the Hebrew Bible, Israelites are the chosen people. Calvinists believed that they had taken over that position. Christians are chosen on the basis of spiritual principles. Because Protestants have a direct relationship with God, the idea was that their conscience would hold them accountable. Protestants – that is to say, Protestant men – were therefore temperate, in control of their body and hence fit for governing and writing laws.

“Protestantism was thus focused on the individual and reason, and less focused on community and ritual than Judaism and Roman Catholicism. Protestants saw other religions as immature and docile, and therefore politically less fit for autonomous self-government. That attitude birthed the idea that Protestantism was the only religion at no risk of resorting to group pressure, dogma or tyranny, as the Catholic Spaniards were portrayed in the early days of the Republic.”

In your book, you explain how the Dutch self-image arises in the link between religion and colonialism. How did this religious hierarchy seep into colonial thinking?

“Calvinists were convinced that they were of the true faith, and therefore also the chosen people to spread the faith. At the same time, they wanted to make a profit from the plantations, which required slave labour.

“Calvinists saw these ‘pagans’ as physically different, and themselves as physically superior. For example, the prominent Calvinist preacher G.C. Udemans wrote that children of Christian men and ‘pagan women’ were half black and half white on the outside, and half pagan, half Christian on the inside. Other texts even argue that the ‘nature of Indians’ is sinful and dirty even if they were to convert to Christianity, so that their children would not be true Dutchmen, but mestizos – a word we adopted directly from the Portuguese.

“This goes to show that the idea of racial purity, visible in the aversion to intermingling, already existed among Catholics. The claim that the Republic did things ‘differently’ from Catholic powers was partly a matter of perception. The true difference was in the Protestant tension around conversion and baptism. Eventually, enslaved people were selectively allowed to convert to Christianity, but the Calvinist church remained exclusive and white. Segregation became an important part of white and Christian supremacy.”

Why is this still relevant today?

“Because the cultural legacy remains, despite modern democracy and the Dutch nation state being organised differently from the Republic. Even secular Dutch people still believe strongly in autonomy, good governance and moderation. These aren’t bad values in and of themselves, but we tend to overlook how those values were deployed to justify hierarchies. As a result, the idea persists that we’re ‘born’ with the capacity for reason and others are not.”

‘Rutte was a driven ideologue who deliberately shifted to the right and had already been convicted while state secretary for inciting discrimination’

How do you see that self-image reflected in politics today?

“Mark Rutte’s entire premiership was telling. Rutte is the embodiment of the Dutch self-image. He fitted perfectly into that image of the rational, down-to-earth, non-ideological leader. At the same time, it was during his time in office that the rule of law became increasingly weak. There was the childcare benefits scandal, which exposed institutional racism. Still, the scandal proved no deal-breaker, as many Dutch voters again voted for Rutte’s party, the VVD.

“Rutte was a driven ideologue who deliberately shifted to the right and had already been convicted while state secretary for inciting discrimination. But the image remained: this is the man eating an apple and riding his bike who keeps the country safe from extremism. That contradiction has entrenched itself so deep into the Dutch national self-image that he easily got away with it.”

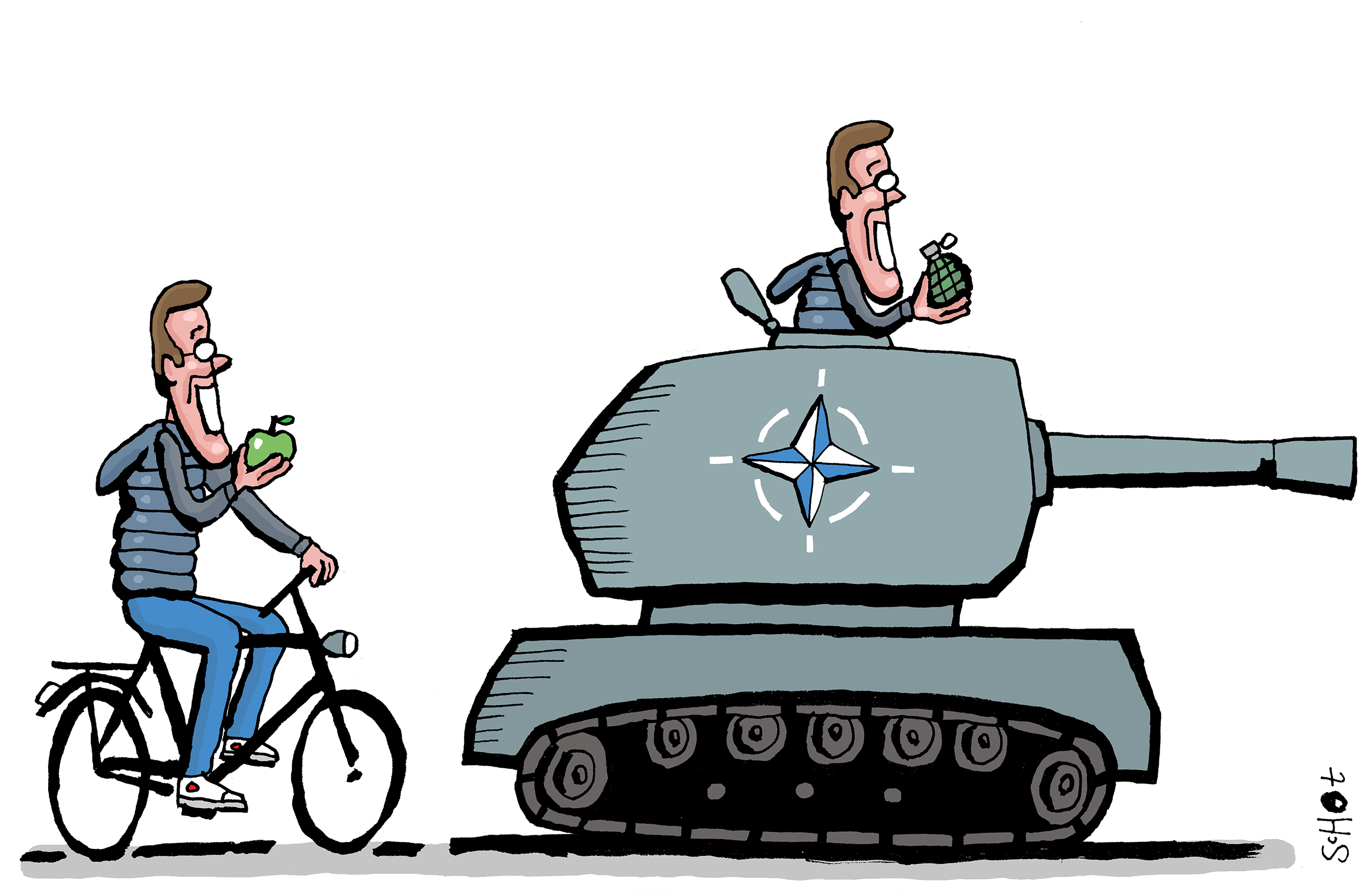

Image by: Bas van der Schot

How do politicians leverage that self-image?

“A concrete example of how Rutte capitalises on the idea that ‘the Dutch are more rational than the rest’ is how he spoke during the pandemic about the ‘smart lockdown’. In one of his first press conferences, he spoke of ‘a mature, proud democracy’ in which ‘people are able to behave responsibly’. The Dutch didn’t need coercion, because they could regulate themselves. By implication, a ‘dumb lockdown’ was for other countries that couldn’t.

“Another example is a comment made by Jeroen Dijsselbloem, then Labour Party finance minister and also president of the Eurogroup. In the wake of the euro crisis, he suggested that southern Europeans were spending their money on ‘booze and women’ and then turning to northern Europe for help. When there was a fuss about this, Dijsselbloem tried to set the record straight by invoking Calvinism; something that, in his words, ‘other countries may not understand’.

“Therein lies the whole idea: that northern Europeans, and above all we as the Dutch, are the only ones who can keep the accounts, balance the books and do everything in moderation – economically as well as sexually. That idea of sexual moderation also originated during the time of the Republic. Hugo de Groot already wrote that sexual self-control is something typically Dutch. That fuels the idea that only the Dutch are fit for responsibility and governance.”

How does current migration policy relate to the image of the Netherlands as a moderate state under the rule of law?

“The discourse on asylum again shows how racialisation works. Asylum seekers are portrayed as a danger, and especially as sexually threatening. The pejorative term ‘testosterone bombs’ is a clear example of this thinking. It touches on a long history in which sexual intemperance was systematically projected onto non-white people, in contrast to supposedly controlled, white masculinity.

“The current migration policy is clearly totally inconsistent with the self-image of the Netherlands as a moderate democracy. Minister of Asylum and Migration Faber was happy to put up signs saying ‘Here we are working on your return’. Politicians are openly distancing themselves from international law. That’s no longer reasonable governance, but performative cruelty.”

Another issue where the self-image of moderation is difficult to reconcile is increasing militarisation. What’s your take on that?

“Of course, it’s interesting that Rutte of all people is the one who has to prepare us for the transition to a war economy. He’s always been good at normalising things that should never be normalised, but even this increasing militarisation is now being sold as a game of checks and balances. If a superpower invests in defence, so should we. It’s classic chequebook logic.”

‘I find it worrying that there was no great shared sense of alarm when the Schoof cabinet was formed’

How do you see this self-image reflected in the Schoof cabinet and the upcoming election campaign?

“Dick Schoof is trying to uphold the image of the Netherlands as moderate, reasonable and decent in terms of governance. But where Rutte could still make it look credible, many people now feel it’s rehearsed.

“I find it worrying that there was no great shared sense of alarm when the Schoof cabinet was formed. The idea that we have our house in order is so entrenched that even many on the left now thought: ‘All right, let those far-right lunatics have a go. This is bound to go wrong’, expecting that voters would go back to the reasonable middle. I actually find that an almost culpable naivety. We see that far-right politics is winning in many countries all over the world, so the logic that things will be all right here in the Netherlands is flawed.”

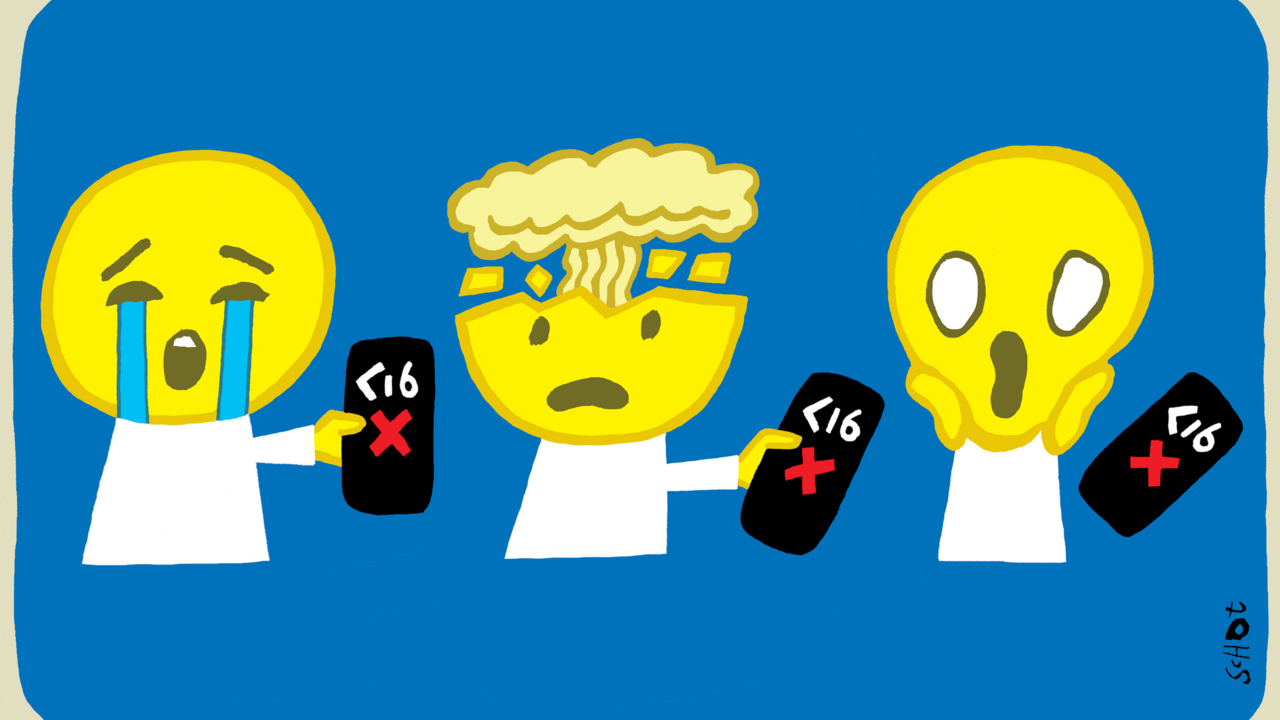

Image by: Bas van der Schot

Could you say a more realistic image of how the Dutch really are is emerging?

“That’s hard to say. The PVV, which received the most votes in the last election, openly advocated replacing Article 1 of the Dutch Constitution. This article guarantees equal treatment and prohibits discrimination. The PVV wants to replace this article with one that establishes the ‘Judeo-Christian and humanist tradition’ as the dominant culture in the Netherlands, thereby ending the principle of equality between all religions. The fact that so many people vote for this plan is always explained as a protest vote, not a conscious choice for supremacy. They fail to understand that appealing to feelings of supremacy is a successful political strategy, also in the Netherlands.”

Recent years have seen increased focus on our colonial past and apologies have been made. Has this changed our self-image?

“I think a lot has changed for the better. Many people, especially people of colour, have worked hard and paid a price for that. The word ‘whiteness’ has become commonplace in many circles. People like you and me, white people, have started thinking a little bit more about our whiteness. We’re capable of such thinking because we now have words to express it. Looking at myself, I couldn’t have had this conversation fifteen years ago.

“At the same time, I see that even those apologies have an aftertaste of ‘We’ve apologised now, isn’t that wonderful? Because that’s how we are: reasonable, taking responsibility for our mistakes. Now we can continue with our lives in a pragmatic way.’ In that sense, I believe the Dutch self-image is a tough nut to crack.”

Read more

-

Why press freedom has never been in such a poor state, and what we can do about it

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

De redactie

-

Manon Dillen

Manon DillenEditor

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-