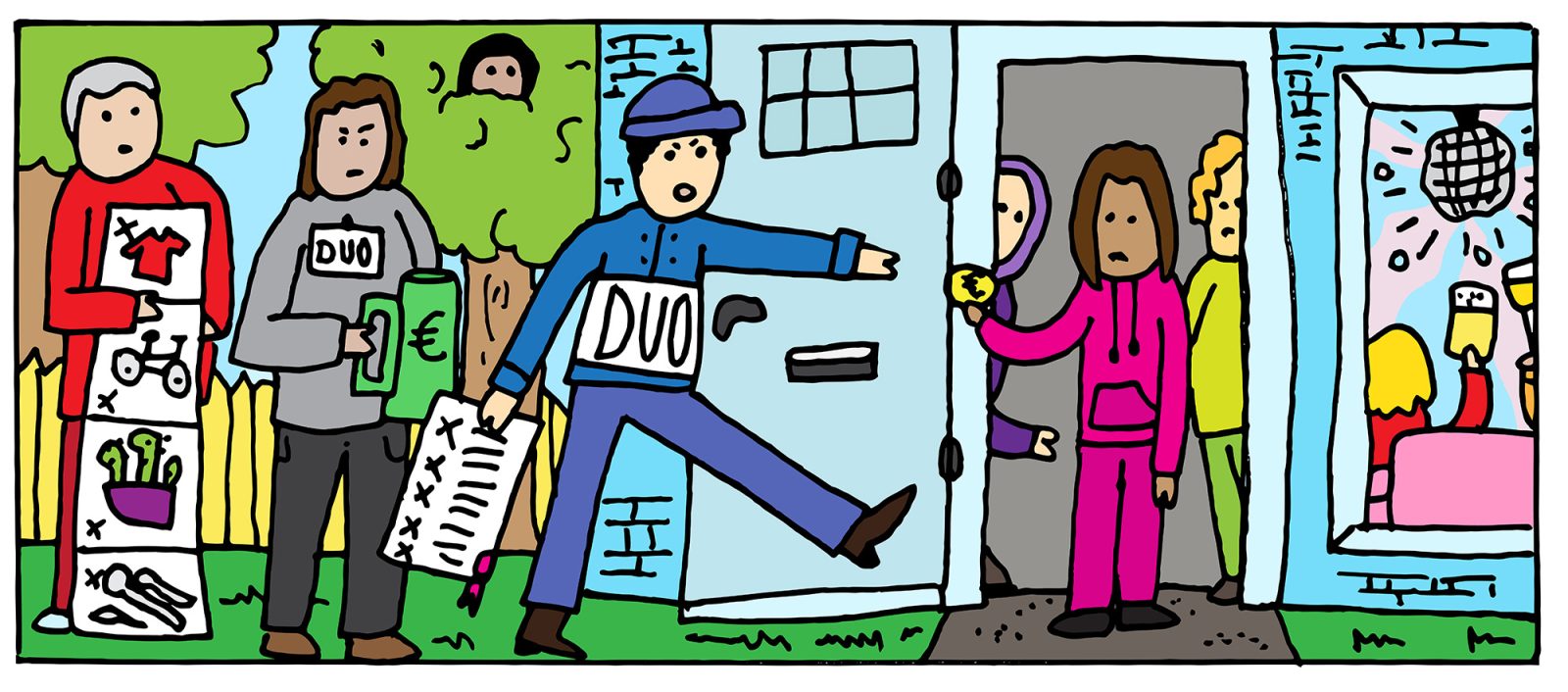

DUO fraud investigators mostly catch students with migration background. ‘That neighbourhood investigation was bullshit’

As part of their efforts to combat abuse of the basic student grant, investigators are knocking on students’ doors. These checks sometimes go wrong, and students with a migration background are often the ones who suffer most, as an investigation by the Higher Education Press Agency, Investico and NOS op 3 reveals.

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

You are about to read this:

- To combat fraud with the grant for students who moved out of their parents’ home, Education Executive Agency DUO conducts home visits and neighbourhood investigations. That investigation does not always go well and often students with a bicultural or migration background are the victims.

- DUO doesn’t record the cultural background of students. But fraud teams and auditors don’t receive training on how to deal with exceptions or cultural differences.

- Experts are shocked by DUO’s modus operandi. They feel cultural differences are not taken into account, see that fraud teams ask leading questions and denounce the way students are flagged as suspects.

- Now that the basic grant is returning to higher education, the government wants to significantly scale up the number of home visits.

- Education Minister Dijkgraaf calls the findings a ‘worrying signal’ and wants to investigate whether DUO’s approach is ‘not discriminatory in a veiled way after all’.

Amir was surprised when he got the message. The Education Executive Agency (DUO) claimed that he does not live where he says he lives, and it therefore intends to reclaim over two thousand euros in student finance and, on top of that, is fining him a thousand euros. In DUO’s view, he is a fraud who is claiming a grant intended for students who live away from home (almost 300 euros a month) despite actually still living with his parents (for which the grant would only be 100 euros a month). He has no idea where they got this idea. He lives with his aunt and uncle and their young son and has his own room at their place. Nobody has asked him anything, and DUO has not been inside his place. So what is going on?

Aside from his senior secondary vocational studies, Amir works a lot, including as a taxi driver. “I’m a workaholic”, he says. “I had three side jobs. Work, go home, shower, change quickly and straight on to the flexible shift in the evening.” DUO’s report states that investigators dropped by for a ‘home visit’ on six separate occasions. But they always came during the day, always between nine and five. It should not surprise them that nobody is home at those hours, according to Amir. At least once, they should have come round in the evening, when his aunt and uncle would have let them in to see his room.

‘But the thing is, I did actually live there’

But that never happened. The enforcement team pressed ahead with what is known as a neighbourhood investigation, which involves asking neighbours who they think lives at the address in question. In Amir’s case, they spoke to two neighbours, both of whom stated that a Moroccan couple lives at the address with their young son. The interview reports show what was said. “Is there a student living there as well? No. I’ve only seen those people and their child. I haven’t seen anyone else. That’s all I know.”

Two such statements were enough for DUO to label Amir a fraud and make him repay thousands of euros. He cannot believe it. “It’d be fair enough if it were true that I didn’t live there. But the thing is, I did actually live there.”

Recoveries and fines

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

Amir is certainly not the only one to be targeted by DUO. Since 2012, close to 25 thousand home visits have been conducted, and on almost 10 thousand occasions, the investigators concluded that fraud (or as DUO calls it: abuse) was involved. 13.2 million euros worth of basic student grants have been reclaimed, and 7.4 million euros worth of fines have been issued.

In recent years, only those studying in senior secondary vocational education were eligible for the basic student grant, as it was scrapped for higher education in September 2015. Nonetheless, it is common knowledge that the grant will be reintroduced from the start of the next academic year, so students in higher education will be facing the prospect of checks once more. Furthermore, the government intends to significantly ramp up the number of home visits. Robbert Dijkgraaf, Minister of Education, Culture and Science, has told the Dutch House of Representatives that this number is set to rise to 4,000 a year, which is the highest it has ever been. The current record is 3,769 home visits in 2014. It was just under a thousand during the 2020 pandemic year.

The obvious question is whether these checks are having the desired effect. It is far from clear that they are. At least one in four students challenging the decisions in the courts are winning their cases. Moreover, we have known since the childcare benefits scandal that it is also perfectly possible to lose such a court case unfairly.

“That neighbourhood investigation was major bullshit”, says Amir. “I know my neighbours’ daughters, so I dropped by. They said: yes, you live here. We don’t know what our parents were on about either.” His neighbours do not speak Dutch well, he says. “They probably didn’t understand what was being said and just went along with the conversation.”

Leading questions

When we asked experts about it, they were shocked by the neighbourhood investigations and the drastic conclusions that DUO is reaching based on them. Can they simply be relied upon to establish the truth? What is the risk of misunderstandings and mistakes? And is there a possibility that cultural differences could play a role?

‘Not every student is obviously a student’

Annelies Vredeveldt, an associate professor at VU Amsterdam engaged in researching witness testimonies who often acts as an expert witness in complex court cases, is happy to offer an opinion. “In Turkish and Moroccan culture, the gap between authority figures and the public is much more pronounced”, she explains. “This means that people have a greater degree of respect for authority figures and are more inclined to go along with what they want from them. So when a DUO representative turns up asking questions, there’s a very real chance that the person answering will just say ‘yes sir, yes sir, three bags full sir’.” This is especially true when it comes to leading questions, as is the case here, she believes. “The key word is ‘student’. Not every student is obviously a student. How would they know whether or not their neighbour is a student?”

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

This point is echoed by Jannie van der Sleen, a legal psychologist who provides forensic interview training. Not everyone has the same ideas about what a student is. “It depends on your own background. If you went to university yourself, you might regard only university students as students and see senior secondary vocational students as school pupils.”

Vredeveldt adds: “If DUO investigators ask ‘Who lives there?’, people will talk about the people they see regularly rather than about someone who does live there but is often not around. If someone is always out and about, they might not get mentioned.” Social cohesion in the neighbourhood is another important factor, she explains. “Some neighbourhoods have five houses, and everyone knows everyone because they get together for a barbecue every year. It’s different if you live in a flat in a major city.”

Cheating was easy

You might be tempted to think that concrete evidence is hard to come by in such neighbourhood investigations. But concrete evidence is not required. The burden of proof has been reversed. The standard of proof that DUO has to meet is that it is plausible that a student actually lives somewhere else, whereas students have to present concrete evidence to the contrary if they are to succeed in allaying suspicions. The one responsible for this is Ronald Plasterk (PvdA), Minister of Education, Culture and Science from 2007 to early 2010. He is the one who initially launched the fraud hunt.

It may be true that something had to be done, since cheating the grants system was pretty easy back then. Students living at home only had to give a different address to get their hands on several thousand euros of free money from the government over the years because they were supposedly living on their own.

‘Good example: the sphere of childcare’

But how do you go about catching frauds? Plasterk was not going to take any risks. He looked at ‘the sphere of childcare’, for instance, taking the view that one can learn a great deal from ‘good practices within other organisations’. This was still several years before the childcare benefits scandal.

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

Eventually, Plasterk came up with the idea of fining alleged frauds and putting the burden of proof squarely on them. Plasterk’s successors likewise believed that this problem needed to be tackled. Initially, they estimated that basic student grant fraud amounted to 27 million euros a year, but they subsequently raised their estimate to 40–55 million euros. “It’s truly shocking”, said Secretary of State for Education, Culture and Science Halbe Zijlstra (VVD) in 2011. “We need a strict approach to reduce the abuse.” And he is not the only one to have taken this view. The Labour Party (PvdA) insisted on penalties for anyone aiding and abetting the frauds, such as uncles and aunts.

Checks got underway in 2012. The annual revenue from fines and recoveries is not even that high (the record is 4.8 million euros in 2014, and in recent years, it has been a few hundred thousand), but DUO defends the approach by citing the preventive effect. Students are cheating the system less because they know there is a risk of getting caught.

Appeals

Amir lodged an objection to DUO’s decision. He submitted a statement from his neighbour that she gave incorrect information because of the language barrier. His uncle and mother also stated that he is indeed living with his uncle. When DUO dismissed his objection out of hand, Amir took the matter to court. “I was certain the judge would rule in my favour”, he says. “The facts are plain as day. I lived there, and that’s a fact.” But no, the judge rejected the appeal. Amir’s relatives’ statements are subjective and therefore cannot play a role. The judge saw ‘no grounds to believe’ that the neighbour’s original statement ‘was not made truthfully or contains inaccuracies’.

‘When someone goes back on a statement, it suggests that something is amiss’

“A red flag”, says witness testimony expert Annelies Vredeveldt. “When someone goes back on a statement, it suggests that something is amiss, that further investigation is warranted.” But the judge sees it differently. “The neighbours made pretty much identical statements independently of each other”, and these statements “clearly and unambiguously indicate that there is no student living at the address listed in the Personal Records Database (BRP).” On appealing the ruling, the Central Appeals Tribunal (CRvB) reached the same verdict, bringing an end to the matter.

Girl moving out

We also spoke to Zahra, who, like Amir, has a migration background. She wants to rent a room, but that is easier said than done. “I’m Dutch, but my mother is still very much an Afghan woman, so she’s worried about how doing so would affect my reputation.” Instead, she went to live with her elder brother and sister-in-law. Her mother is fine with this.

However, DUO found it suspicious that she was living with her brother and went to investigate. Again, DUO conducted a neighbourhood investigation, but in her mother’s area. A neighbour told the enforcers, truthfully, that she would still regularly see Zahra at her mother’s house. Two other neighbours said the same. Armed with this information, DUO concluded that these were not visits and that she lived there! Zahra was required to repay her student grant and received a fine. All in all, this would cost her 13 thousand euros.

And it did not stop there. She says the investigators also went to her employer, the local authority, where she had a student job, to ask questions about her address. As a result of this enquiry, her manager is no longer willing to offer her a contract, as previously promised.

‘The students I see often have a migration background’

Zahra does win her court case. One of the investigators was a work placement student, which is disallowed by the court. Hence, DUO was taken to task for a procedural error, but Zahra feels that this is not enough. She wants DUO to acknowledge that the investigation itself was shaky. She filed another case against DUO, which she also partly won. As a result, DUO was ordered to pay Zahra several thousand euros because of the psychological distress caused to her. To her disappointment, she did not get the recognition that the investigation was poorly handled.

Migration background

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

Is it a coincidence that these students are both from migrant backgrounds? It seems to play a role in many court cases. The lawyers we speak to sometimes bring it up themselves. “The students I see often have a migration background”, says Rotterdam lawyer Jacqueline Nieuwstraten, for example. Others confirm the suspicion. The students with basic student grant-related issues who show up during the walk-in hour of Tilburg lawyer Rachid el Bellaj always have a migration background. “Never someone with a Dutch name.”

We wanted to find out more. Teaming up with fellow journalists from NOS op 3, we drew up a list of seventy lawyers who have litigated against DUO over the past decade. We called them to ask two questions: how many such cases were you involved in, and in how many of them did your client have a migration background? “All of them”, is the typical response to this last question. Or: “All but one!”

The 32 lawyers willing to share data conducted a combined total of 376 cases. In 367 of these, their client was a student from a bicultural or migrant background. That is 98 percent, covering roughly a quarter of all lawsuits relating to the basic student grant over the past decade (1,463 cases).

“Shocking”, thinks Gijs van Dijck, professor of Private Law at Maastricht University, who studies ethnic profiling by government organisations. He is one of the experts to whom we submitted our findings. He is critical of the way in which DUO labels students as suspects.

Who is suspicious?

DUO does not just do spot checks on students supposedly living away from home. To maximise its chances of success, students are first filtered, with DUO using ‘risk profiles’. Factors include the distance between a student’s address, the parents’ address and the site at which the education is being provided.

It is suspicious when students move in next door. It is also suspicious if a student goes to live somewhere fairly far away from where the education is being provided, despite the parents’ house being nearby. Other risk profile factors include age and ‘type of course’, with senior secondary vocational students being more likely to be subjected to scrutiny.

There is no scientific basis for this selection. “That’s a big problem”, says Professor van Dijck, “because it means you actually have no idea what you’re measuring. Working with an algorithm is all well and good, but you need to know exactly what it does to avoid singling out one group.”

After this initial selection of suspicious students, a special department within DUO will do some online sleuthing. Does this person live in student housing? If so, then it probably checks out. Is someone registered as living with someone else? Sometimes, there will be evidence online that they are in a relationship, which means there is no need to send out an investigator.

This second screening process is carried out by humans, and people quite simply have their own expectations and prejudices. That might go some way towards explaining why so many lawsuits are filed by students with migrant backgrounds. Are cultural differences a factor in DUO’s investigative activities?

‘There is no policy on dealing with cultural differences’

“DUO doesn’t make a record of the cultural background of a student, parent or debtor”, the agency insists. “That point alone is enough to rule out the possibility of us treating people differently on the basis of cultural background. So no, there is no policy on dealing with cultural differences. Regulatory authorities are required to take into account official Christian or Muslim holidays, though, and to refrain from conducting home visits on those days.”

But do the fraud team and investigators perhaps receive training on how to handle exceptional cases or cultural differences? The answer is no. “DUO does not provide specific training to deal with cultural differences to fraud team staff and investigators.” That said, staff are given work instructions ‘geared towards fostering the quality of the investigation and preventing arbitrary decisions’. Exceptional circumstances can prompt ‘justifiable deviation from the instructions at any time’.

We endeavoured to ascertain whether DUO itself is alert to the possibility that mistakes are occasionally made, but that does not seem to be the case. For example, DUO has never properly evaluated the policy. “We did discuss it together”, says spokesperson Tea Jonkman. “But we didn’t put anything down on paper.”

Interview

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

With some persistence, we got a chance to interview the manager and a former staff member of DUO’s Enforcement and Inspection Department. According to them, their investigative activities unearth all kinds of fraud. There are sometimes dozens of students registered at a single address at which only a few people could actually live. There are also cases of two families ‘swapping’ children, with student A supposedly living with family B and student B with family A. “The set-up is even circular sometimes”, says the staff member. “That means we can follow the trail from family A to B to C to D and eventually end up back at family A.”

In case of suspicion, DUO sends out investigators, who drop by. Often, DUO staff in Groningen will make the assessment on their own, but when in doubt, they will seek a second opinion from a colleague. They confer and monitor each other.

‘The childcare benefits scandal hasn’t prompted any changes for DUO’

DUO is, of course, well aware that such checks have been under a magnifying glass since the childcare benefits scandal. However, unlike the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration, DUO says it does not look at origin or operate a ‘blacklist’. Nor do the data on recovery of the basic student grant get sent anywhere else. Students will not get a criminal record for illegitimate use, for instance. DUO does not request information from the Tax and Customs Authority, the Ministry of Justice or other government organisations for the purposes of its investigations either. So the childcare benefits scandal has not affected DUO’s approach, says the manager: “The approach has been tested, but no changes were necessary.”

The fact that DUO might sometimes make mistakes does not occur to her. To err is human, the manager says as a sweeping statement, but she is unwilling to take that point to its logical conclusion. ‘Mistakes’ is not in her vocabulary either. “When we talk about mistakes at DUO, we mean things like typos.”

So does DUO never improve its approach? Sure. The service claims to be engaged in ‘continuous’ learning, when a judge rules in favour of a student, for example. That will prompt DUO to adapt its approach from time to time, albeit with some delay. “A court ruling today may well pertain to a home visit conducted three years ago.”

But just because you improve something does not mean that the previous way of doing things was inherently wrong, even if the trigger is a court case loss – that is the prevailing notion at DUO. “The judge sometimes thinks that we ought to have substantiated our position better or that we should have asked more questions as part of the investigation”, says the manager. “I’ve noticed that judges are becoming stricter in that regard. They’re very critical.”

Court cases

Image by: Pauline Wiersema

Far from all judges seem all that critical, though. DUO recently won a court case centring on a Syrian student who spends a lot of time with his ailing mother. He rents his own property, but does he actually live there? Or is he actually always with his mother? The property contained very few items that belonged to him. The student argued that this is because he does not have much money with which to buy things, but the judge was unconvinced. His other arguments fell flat too. The fact that he has been renting the property since 2016, that he pays the rent himself, that he has the keys to the property and that his phone automatically connects to the Wi-Fi network did ‘not persuade the court to reach a different conclusion’.

You do not get the benefit of the doubt so easily. DUO has had other victories, such as in a case in which the court ruled that: “Furthermore, in the picture taken, the room does not look like a student’s room”.

Still, DUO has had its losses too, such as when investigators are overly hasty. In one of the home visits, the investigators’ own report confirms that they finished within just 19 minutes, including the ‘journey time’ from the street to the block of flats and from the front door to the bedroom and back again. “This will have taken an estimated four to six minutes”, said the ruling. And then there is the admin work, such as filling in and signing forms. The court took the view that ‘a proper investigation into the claimant’s actual living situation cannot be conducted in such a short space of time’.

In another case, a student happened to be absent for a few weeks due to her room being renovated. The visiting investigators relied on statements made by her younger brother, who also lived there, but who has been diagnosed with PDD-NOS, meaning he has difficulties with social interactions, the ruling pointed out. “He takes questions literally and has trouble making connections.” The judge dismissed DUO’s claims.

Investigators

Home visits are made by enforcement officers from local authorities or private companies. We spoke with some former enforcers, who told us what they look for and what questions they ask. Are there textbooks, is there a bed, are there clothes hanging in the cupboard? And if the student is there themselves, they might ask whether they know which kitchen cupboard the plates are in.

‘Ik dacht gewoon: ik pak je. Ik haat mensen die frauderen’

They come across some crazy situations. Someone once showed the enforcers a baby room for a set of twins and expected the enforcers to believe that he slept on a mat on the floor every night. Of course, they also see some bona fide student rooms, where it is immediately clear that the student is indeed living there. They then write a report for DUO, after which the department makes a decision.

But what about the grey areas? Is it really always clear whether someone lives there or not? One of the enforcers believes so. “I always know immediately if it is a fraud case. You just feel it.” Sometimes, there would be no bed, and the student would claim to be sleeping on the sofa. The inspectors would then not believe that. “Moroccans have these lovely couches – so it is technically possible. But I’d just know.” There were times when residents tried to intimidate the enforcers, she says, but that did not bother her. “I’d just be thinking: I’ll get you. I hate frauds.”

Objection, appeal

Such checks entail all kinds of risk, such as enforcers confirming their own prejudices and then increasingly targeting the same group. Another possibility is elevating the ‘normal situation’ to the status of a normative standard, with anyone who deviates from it having to repay their basic student grant. That fate seems to befall students with migrant backgrounds to an above-average extent.

Confronted with the findings, DUO spokesperson Tea Jonkman initially denies there is any cause to investigate this – assuming this would even be possible. “We don’t know how we’d even go about subjecting that process to scrutiny, precisely because we select on objective characteristics rather than background. We don’t know.”

She calls the overrepresentation of students from migrant backgrounds remarkable. “But we’re not in a position to verify that ourselves”, she says, “because we simply don’t keep those records and don’t know. We don’t get any complaints about it either, neither through the courts nor through the Ombudsman.”

And yet there seemed to be a change of heart a couple of days later, with a written response stating that the investigation had revealed “a picture that DUO was not previously aware of”. “The findings will prompt DUO to initiate a systematic evaluation.”

‘The Ministry of Education will have to learn continuously and endeavour to maintain and formulate our procedures as equitably as possible’

It seems that the student finance agency is still having a hard time imagining that innocent parties are being wronged. For example, DUO is aiming to raise awareness ‘in general and perhaps towards special target groups’ in order to prevent ‘potentially unintended misuse’ of the grant in future. And what about those lost court cases? DUO is keen to stress that it is common for courts to rule in claimants’ favour because of a procedure being followed incorrectly and not necessarily because they were in fact living away from home.

'Disturbing signal'

Robbert Dijkgraaf, Minister of Education, Culture and Science, uses stronger words in front of broadcaster NOS’s camera. He deems it a ‘disturbing signal’ and wants a thorough investigation (‘leaving no stone unturned’) to establish whether or not DUO’s approach might be ‘surreptitiously discriminatory’. He uses various terms: unconscious, unintentional, surreptitious.

“This is the first time I’m hearing of this”, he adds. However, in the wake of the childcare benefits scandal, the government should not be too quick to say that something is impossible and is not happening, he admits. “We’ll pull out all the stops and get to the bottom of this. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science will have to learn continuously and endeavour to maintain and formulate our procedures as equitably as possible.”

Outcome

How are Zahra and Amir doing after their clash with DUO? Zahra is still struggling. She is considering appealing just to secure a critical opinion on that neighbourhood investigation. “I’ve kind of run out of energy”, she says. “But my reputation is at stake here. And I want someone to say I’m not a fraud.”

Amir does not want to be defeated. He lost his case, but it will not get the better of him, he says. That is not who he is. He is much more inclined to keep at it and work hard. “Pay off and move on.”

The real names of Amir and Zahra have been changed in this article to protect their privacy.

This article was produced in part thanks to a working grant for Educational Journalism from the COCMA Educational Fund Foundation and a grant from the Special Journalism Projects Fund. The results of this investigation will also be featured in daily newspaper Trouw and weekly De Groene Amsterdammer.

De redactie

-

Belia Heilbron

Trouw and De Groene Amsterdammer

-

Anouk Kootstra

Trouw and De Groene Amsterdammer

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in Money

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

-

New coalition wants basic grant for university master’s after hbo

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-