‘Anglicisation at university has overshot the mark’

“Can I help you, please?” asks the girl behind the bar at Erasmus Pavilion on the EUR campus. When I respond by telling her I’d like to be helped in Dutch, this leads to a discussion with the Pavilion’s manager. According to him, ‘as much as’ 70 percent of the staff here speak English exclusively, and he wonders what I would do if none of the counter staff spoke Dutch. I counter by telling him that in the Netherlands, I’d expect to be helped in Dutch rather than English. I’m dumbfounded: the Anglicisation at Erasmus University has completely overshot the mark.

As a Dutch student, I have my doubts about the need to adopt English as a lingua franca in higher education. And I am not alone: last year, 180 professors, writers and other prominent intellectuals published a manifesto in de Volkskrant, arguing among other things that Dutch remains the key language of communication within most professional groups. So what is the added value of adopting English?

English-language degree programmes draw a lot of international students – which further reduces the institution’s budget per student, according to the manifesto, and ultimately affects the academic quality of the provided education. What’s more: after graduation, only a small share of these international students (approximately 20 percent) stay on in the Netherlands for longer than five years, according to research performed by Nuffic The Dutch organisation for internationalisation in education. In the majority of cases, the Dutch economy doesn’t actually benefit from their presence, in other words.

‘In the majority of cases, the Dutch economy doesn’t actually benefit from international students’

Observing the on-going Anglicisation at my university, it occasionally seems as if the main focus isn’t providing the best education, but accommodating the Executive Board’s PR machine, which is hell-bent on filling our lecture halls with a chorus of English. But what’s the added value of an English-language subject in the first year of the Law bachelor programme that forces Dutch students to debate each other in English? Many students find the dense legal jargon perplexing enough in their mother tongue. And as professionals, they’ll actually be expected to argue, write and analyse in that same language. So what’s the point of arguing in English?

Why does an introductory programme for prospective students include so many unnecessary English items when everyone attending speaks Dutch? And in the Public Administration programme, why is Statistics taught in English – a subject that for many Dutch students is confounding enough as it is when explained in their own language?

Examples like this raise the question why English is repeatedly preferred over Dutch. While the university’s reasons remain obscure, it is easy to assume that teaching subjects in English is far more attractive from a financial perspective. And in this case, the students’ interests clearly play second fiddle.

‘What’s the added value of an English-language subject in the first year of the Law bachelor programme that forces Dutch students to debate each other in English?’

EUR’s international students – who generally have a very poor command of Dutch – have given considerable impetus to the advance of English in the university’s halls and corridors. Including at the Erasmus Pavilion. Nevertheless, I would like to be addressed in Dutch there, too – on the principle that we need to cherish the Dutch language. In this age of progressive individualisation, Dutch is one of the few things that still connect us, and it is an essential part of Dutch culture. It forms part of our identity.

The steady advance of English in Dutch higher education seems to be an irreversible phenomenon. Still, it shouldn’t be at the expense of Dutch students and of the Dutch language. When it comes to Anglicisation, I believe that the lady and gentlemen of EUR’s Executive Board should be asking the students a different question: “Kan ik je helpen?”. This way, we can ensure Dutch retains a position of prominence at our university.

Lees meer

-

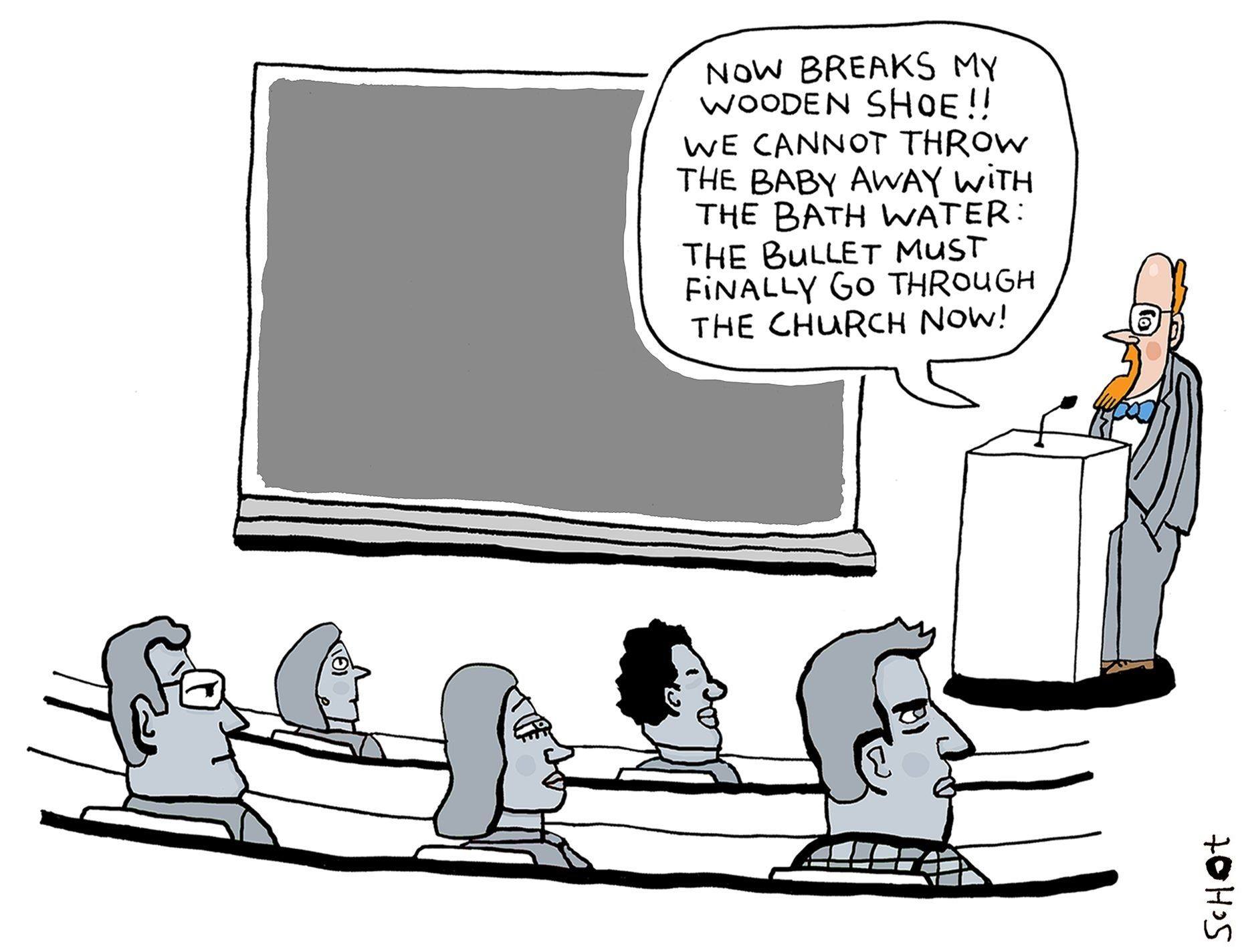

‘Government must reverse runaway Anglicization’

Gepubliceerd op:-

Internationalisation

-

De redactie

-

Eline Burgman

Law student

Latest news

-

Letschert gives nothing away in first parliamentary debate

Gepubliceerd op:-

Education

-

Politics

-

-

Away with the ‘profkip’, says The Young Academy

Gepubliceerd op:-

Science

-

-

House of Representatives wants basic grant for university master after HBO

Gepubliceerd op:-

Money

-

Politics

-

Comments

15 reacties

-

Laura op 6 February 2020 om 16:25

Title is confusing, should be: “studentenvereniging meisje is mad bc she is not good met engels”

-

Hd op 6 February 2020 om 17:38

You should definitely work for EM, maybe people will read it more if you would put your catchy titles on it

-

-

Barbara op 6 February 2020 om 16:30

That might make sense in law, but in most other domains, it’s not only international students, but also international instructors that share the classroom with Dutch students. Recruiting global talent when staffing a course ensures that students get the best educators and universities the best researchers in their domain, not the ones who speak the best Dutch, which is only spoken by some 20 million people worldwide.

Be happy that English has replaced Latin as the language of academia – it’s much easier to learn and speak. -

Kyra op 6 February 2020 om 16:33

To a certain extend, I get your frustration. This is your home country, and you would like to feel at home – part of which is obviously the language spoken.

However, I think your arguments are too one-sided. First, most faculties pride themselves with their “international” approach which plays a big role in attracting both International AND Dutch students. One example are the Bedrijfskunde and International Business Administration Bachelors at RSM. IBA has enormous numbers of Dutch applicants, and the Dutch students value their international environment.

Second, The Netherlands is promoted and promotes itself as the country with the highest English literacy as a second language. Wouldnt this be a somewhat hypercritical fact if universities, where the most educated of the country are, were all in Dutch?What I would propose instead of going backwards and turning English taught programs into Dutch ones is to make it mandatory for international students to learn Dutch/take Dutch courses up until they complete B1 level. Right now, if I, as an international, wanted to learn Dutch “officially”, I would have to pay around €200 for a 3 months course. As you can imagine, my motivation to invest that much is rather low. If the university made the courses cheaper/for free, I am confident that more people felt inclined to learn Dutch even with free will.

The way out here is not to “hate” on the Anglicisation of the university but to find a middle ground to foster our community.

-

Cerine op 7 February 2020 om 04:32

Learning in English exponentially increases your international orientation, opening a lot more opportunities for you. Also the language of academia is English. Not only the literature but also the books used, journals published etc. Also when you get to a certain level of education, chances are your interactions with non-Dutch speaking people (in work, in life) exponentially increase in todays international labor market. You literally still speak Dutch at home, in your daily life, with friends, speaking English for less than five hours on Monday to Friday is not an existential threat to your identity.

-

Norma op 7 February 2020 om 13:35

“De Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam (EUR) is een internationaal georiënteerde onderzoeksuniversiteit”. This is the description available in the website. I mean, was this person aware that she was joining an international university?

“Why does an introductory programme for prospective students include so many unnecessary English items when everyone attending speaks Dutch?” How is this person so sure that everyone attending speaks Dutch? Seriously, evolve and get a life. -

andriy op 7 February 2020 om 15:20

Allow me to disagree with the following, Eline: ”In the majority of cases, the Dutch economy doesn’t actually benefit from international students” since 80% leave the country.

Those 80% will in fact: paid for their education in the past; in future will come to NL on holidays and spend money here, directly or indirectly hire Dutch companies/buy Dutch products, use Dutch legal system and Courts when running business internationally, etc….

Understand your concerns and difficulties with English, but for your own benefits and greater work opportunities, do an effort and master this language. Professional world is truly global these days, no room for Dutch, French or Americans – all of them need to work together and communicative efficiently… dutch is not an option in this situation…. -

Jeff op 7 February 2020 om 15:59

Lekker tolerantie

-

George op 7 February 2020 om 16:44

I have never read a more close-minded opinion article on the EM magazine.

The fact that English had been decided as a teaching language for some programs means that there are only more opportunities for the best talent from both Dutch and non-dutch backgrounds to interact together and share insight. This does not destroy any culture but only enhances the perception of individuals.

-

Q op 8 February 2020 om 15:59

Weird, according to her logic that since she’s in the Netherlands she expects to be helped in Dutch, then when she goes on holidays does she expect to also be helped exclusively in the local language?

-

Tancredi Rapone op 9 February 2020 om 14:40

This is an incredibly offensive and ill-informed article. In principle I agree that Dutch students studying law who will have to use the Dutch language to argue in court should also practice in the same language. That’s it the only reasonable statement in the article. International students pay for their tuition just like Dutch ones and in fact pay a great deal more if they come from outside the EU. The reason why courses in Dutch programs are in English is because you have the opportunity to benefit from learning from an international professor who is probably the most qualified among available faculty to teach that course. This is something you should be grateful for, as it raises the ranking of the university and consequently the value of your degree. Lastly, your argument that a majority of people leave the Netherlands they don’t add value to the Dutch economy is typical of a person who has never opened an economics textbook. The Netherlands has gained the place it has today as one of the world’s wealthiest countries by trading internationally in the past and opening its home economy to international companies and workforce seeking to relocate to take advantage of this country’s excellent infrastructure and internationalisation. This would not be possible if they could not rely on a pool of highly skilled, english speaking, international labour force coming from the Dutch universities. I suggest you form better arguments before presenting such provocative, anachronistic and, quite frankly, whiny, opinions.

I’m apalled that they would publish an article which has the express intention of making international students feel unwelcome, which contains such unsubstantiated and poorly reasoned arguments, in the university journal. Bravo ?

-

ZA op 9 February 2020 om 21:38

What an ill-informed article with strange nationalistic tones.

Eline, International students pay 5 times the tuition fees (€10.000 p/j) that Dutch students do to attend the university; they pay rent; travel and purchase consumer goods and services, all without access to any benefits or subsidies. How does this not contribute to the economy as well as the global reputation of Nederland?

The appeal of EUR is that it is a world renowned university.

Not because it has an insulated, Dutch only speaking environment but rather because it attracts brilliant minds from across the globe, which elevates its status and academic contribution. Don’t discount the value that internationalisation adds to the institution and the degree you will obtain from it. -

silver op 19 February 2020 om 12:23

I can bet my own lifein the fact that this lady’s political stance is right-wing/far right. Obnoxious and xenophobic as they are. Unable to see past their little, unimportant and boring rich white lives. It is outrageous that the magazine of an international university such as Erasmus gives space to someone defending the exact opposite of this university’s ethos. Doesn’t make sense even as an editorial policy.

-

J. Doornik op 7 March 2020 om 01:51

Quoted;

.. which further reduces the institution’s budget per student, according to the manifesto, and ultimately affects the academic quality of the provided education.

Why should the instutitions budget per student be reduced by Lecturing in English? Do law students no longer learn that such a statement needs an argumentation ?” (according to the manifesto”is not enough) And why should the academic quality of the provided education been affected by the English language? Argumentation? Explanation? Do you think this would alter any educational content , and I so and how is this measured? I would not think so.

Comments are closed.

Read more in Opinion

-

Minister Letschert and the academic tower

Gepubliceerd op:-

Column

-

-

Spinach seed wounds

Gepubliceerd op:-

Column

-

-

Leftover dame blanche

Gepubliceerd op:-

Column

-

Rein op 6 February 2020 om 16:15

This is just showcasing the intolerance to international students. This whiny behavior just because you have to make a slight effort of communicating in english at an international setting? There are plenty of universities that dont have international campuses you could attend in the country. Besides, most literature in psychology, social sciences, philosophy, and a great other deal of subjects is produced in english, and most of the advances of those areas have literature in english. Sticking to dutch would be detrimental and restricting students to learn from outdated sources. Im appalled they let people with such narrow views of society, considering what is good for a country only on economic terms and basing arguments on nationalism above all, be a voice to hear in a magazine that not only represents dutch but the international community of Erasmus.