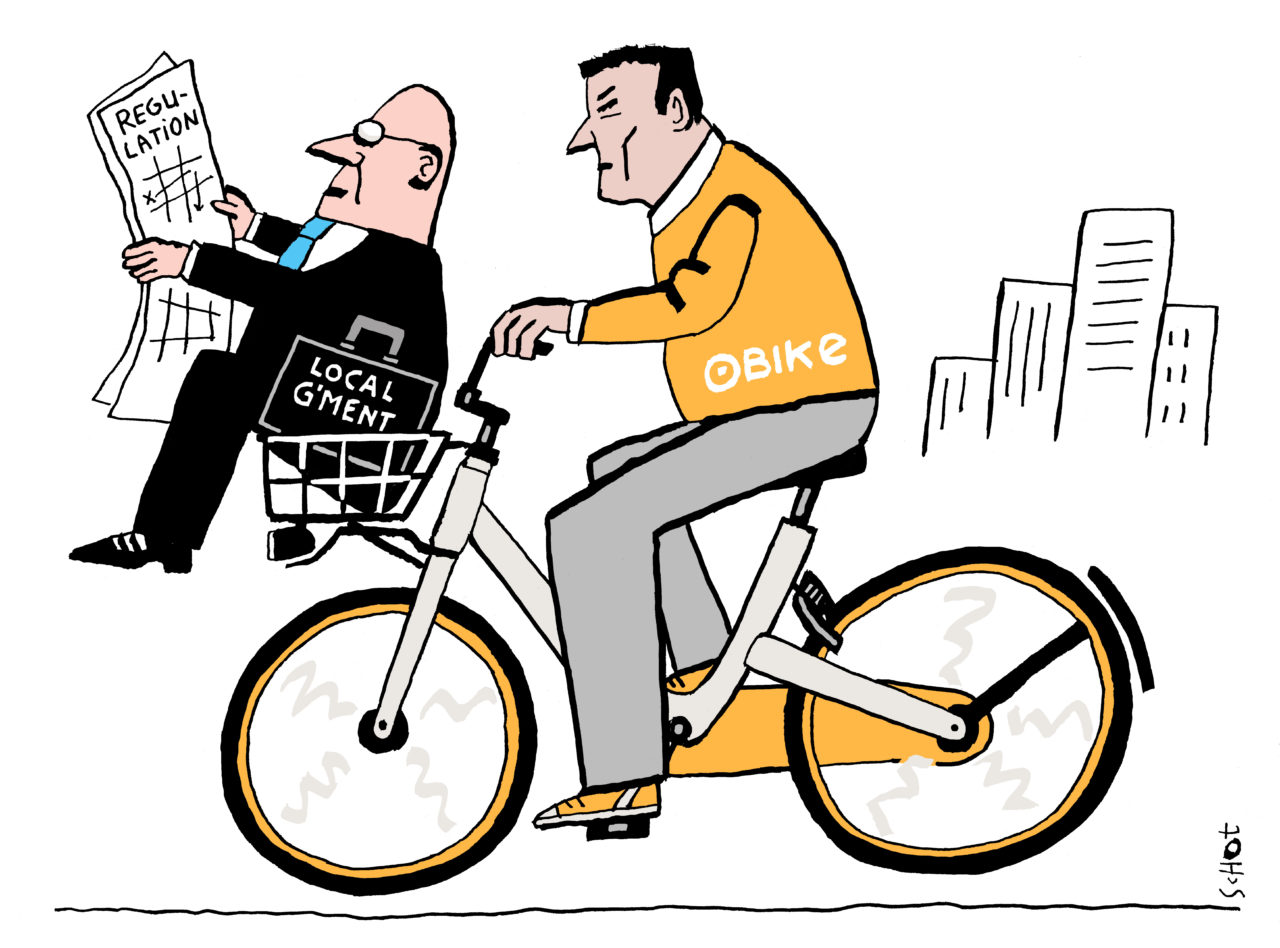

Are you allowed to just flood Rotterdam with oBikes?

No saddle, upside down, stacked ten high: since the summer, the oBike has been an indispensable part of the Rotterdam street scene. But should such sharing economy companies be allowed to make a profit on the back of a municipality? Legal expert Stefan Philipsen says yes: “Create space, make exceptions and see what happens.”

Stefan Philipsen studied law at Radboud University Nijmegen. In 2012, he embarked on his PhD research at Erasmus School of Law into the freedom of school foundations. Prior to this, Philipsen also worked at the House of Education of the Education Council. He is associate professor of Constitutional Law at ESL and editor of the magazine School & Wet about the world of education law. Philipsen has his own bike, so doesn’t use an oBike.

Uber, AirBnB, oBike: the sharing economy seems to be on a roll. What is it exactly?

“The sharing economy comes in two variants. In the first version, a private individual says: I’ve got something I don’t use a lot, like a drill, and I want to make it available to other people. And then there’s a commercial variant, like the oBike. That company says: not everyone needs a bike every day, so we’ll make bikes available that people can pay to use.”

That sounds positive. When does a sharing economy become problematic?

“In themselves, sharing economies are often not illegal. But when a sharing platform becomes successful, it may come into conflict with the public interest. Take AirBnB, for example. Initially it’s not a problem, but when it becomes successful, excesses occur. Apartments are rented 24/7, by raucous British youngsters, for example. Other problems arose with Uber and delivery services, such as worker’s rights.”

How can municipalities best address the problem?

“The first question that municipalities need to ask is whether there are any problems. Take oBike. The company suddenly deposited five hundred bikes in a handful of places with no prior consultation. That caused unrest among the local inhabitants. In such a case, you have to reduce the service to a form that reflects a city’s goals. Sometimes municipalities need new laws and regulations; sometimes the existing ones are enough. But the problems with oBike seem to have been resolved, because the bikes are now evenly distributed throughout the city.”

If there isn’t a real problem, what do you advise the municipality to do?

“As a municipality, don’t be too narrow-minded, don’t focus too much on regulations, but see how the initiative can work in your favour. Decide mainly what you want to achieve and how a new initiative can contribute. Rotterdam has mobility goals, for example. In addition, the municipality is trying to get more people cycling. In Zuid, there are many big families who don’t always have the money to buy a bike for each member of the family. With an oBike, you can easily offer these people a bike. The city thus solves a social problem in an affordable way.”

But a lot of people are still unhappy about the bikes. In Rotterdam-West, the residents moved the oBikes from an overfull street with a delivery bike.

“I can understand that. It can be very irritating if you wake up one morning, leave the house and suddenly there are ten of these orange and grey bikes in your street. Often they’re badly parked too. And they’re rather noticeable, so you see immediately that they’re oBikes. But to be clear: that problem doesn’t only apply to oBikes. When I leave home, I see bikes all over the place parked in the wrong place.”

Are the residents in Rotterdam-West allowed to move the bikes, though?

“Yes, as long as they don’t destroy or damage the bikes. But the bikes are owned by oBike, so you have to be careful with them. The Dutch Civil Code determines what you can and can’t do. Then every municipality has its own byelaw (APV) governing the use of bikes in the public space. This states, for example, that you may not leave a bike unattended in a public space for longer than four weeks, like in your street. And you aren’t allowed to leave a bike so that it forms an obstruction on the pavement, for example leaning against a front door. And if your bike becomes a wreck, the municipality may take it away.”

And oBike? Did they need a permit for the bikes or can a company like that just drive into the city with a lorry load of bikes?

“Each municipality is different. According to the Amsterdam byelaw, you may not offer services on or near the public road. That rule is primarily intended for people who want money for washing windscreens at traffic lights. The municipality of Amsterdam used that provision to move oBikes and other shared bikes from the city. The number of bikes in Amsterdam is a serious problem, so there is limited scope for such initiatives there. Rotterdam doesn’t have that kind of provision. oBike just got hold of a lorry and brought in five hundred bikes.”

“As a municipality, don’t be too narrow-minded, don’t focus too much on regulations, but see how the initiative can work in your favour.

Imagine you’re a councillor in Rotterdam. How would you improve your relationship with oBike and other sharing platforms?

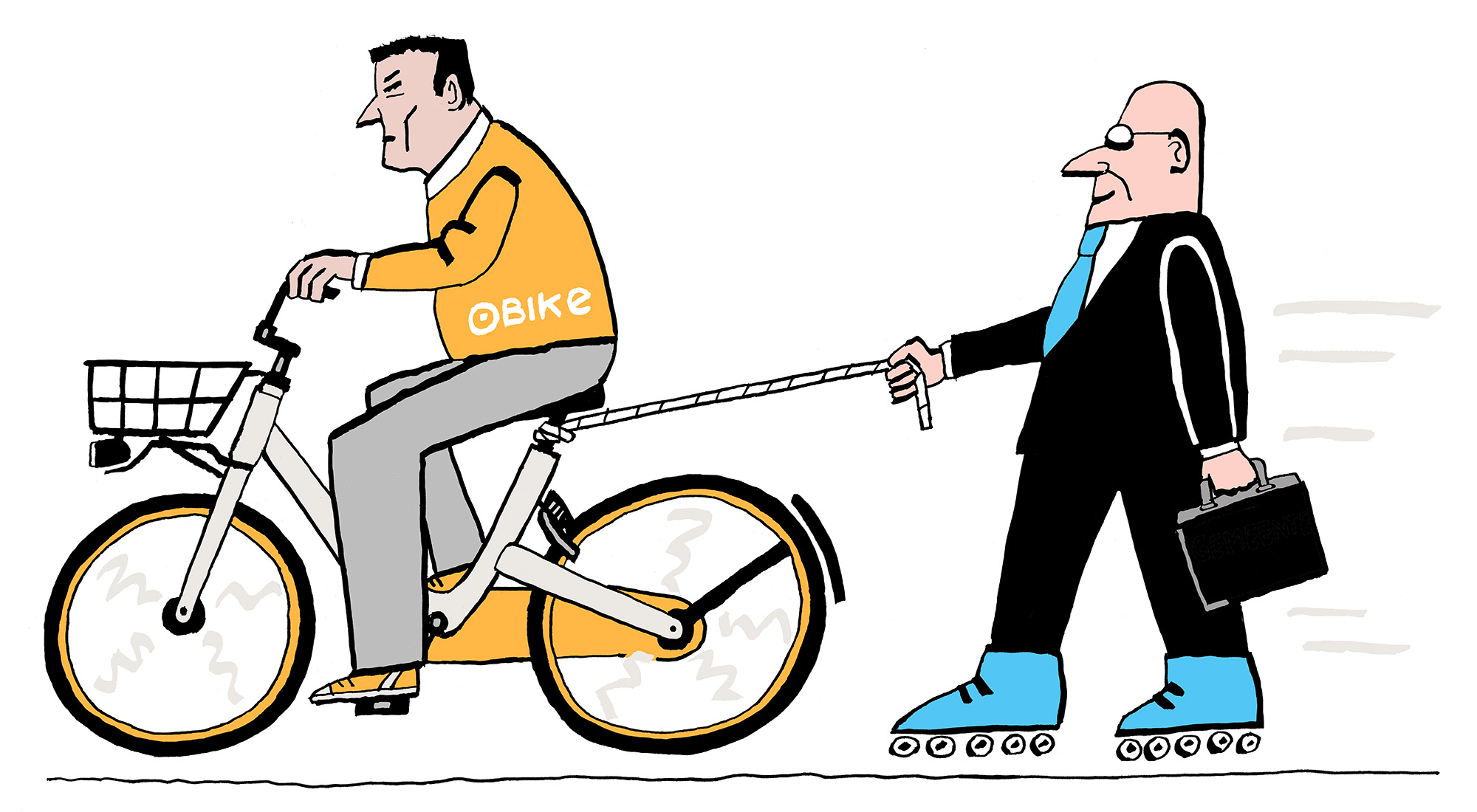

“You can’t really ban initiatives like oBike, Uber and AirBnB. As a municipality, you are confronted with them and sometimes developments go faster than you expect. I wouldn’t apply the existing regulations to these new initiatives, such as the APV byelaw regulating bikes in the public domain. These regulations don’t take into account the space which oBike needs to work, for example. Moreover, in the Netherlands, we are totally overregulated. There’s a regulation for everything! There are five regulations just for parking a bike. If you apply those regulations to the sharing economy, that will be the end of those platforms.

“As an alternative, you can make exceptions for the sharing economy, but that’s not without problems. In law, we normally work with general regulations which offer legal certainty to everyone, created by democratically chosen bodies like the municipal council. If we make too many exceptions to these general regulations on too many occasions, the principles of legal certainty and equal rights come under pressure.

Municipalities must therefore ask themselves what they want to do with the sharing platform or other new initiatives, now and in the future. Is there a problem? And how can the problem contribute to the municipality’s goals? Barcelona, for example, chose only to make a bike sharing system available to its residents, not for tourists. As a government, you then create scope for developments, whilst keeping the new initiative manageable.”

Critics say the opposite: oBikes are parked in the public space and benefit from costs incurred by that municipality.

“People often concentrate on the disadvantages of such initiatives. But they also bring advantages to the municipality. To solve problems, such as the last kilometre in the Public Transport or the lack of bikes in Zuid, they often buy expensive systems with bikes and docking stations. Businesses like oBike say: municipality, there are no costs to you. We’ll pay because it earns us money. That’s a win-win situation.

“Furthermore, we are moving towards a different type of economy. It’s now less about our own property and more about sharing. It’s evident to me that as a government, you have to take that into account. The question is just in which form. I’d say: start with small initiatives. Create space, make exceptions and see what happens.”

Image by: Bas van der Schot

De redactie

-

Inge Janse

Inge JanseEindredacteur

Comments

Comments are closed.

Read more in The Issue

-

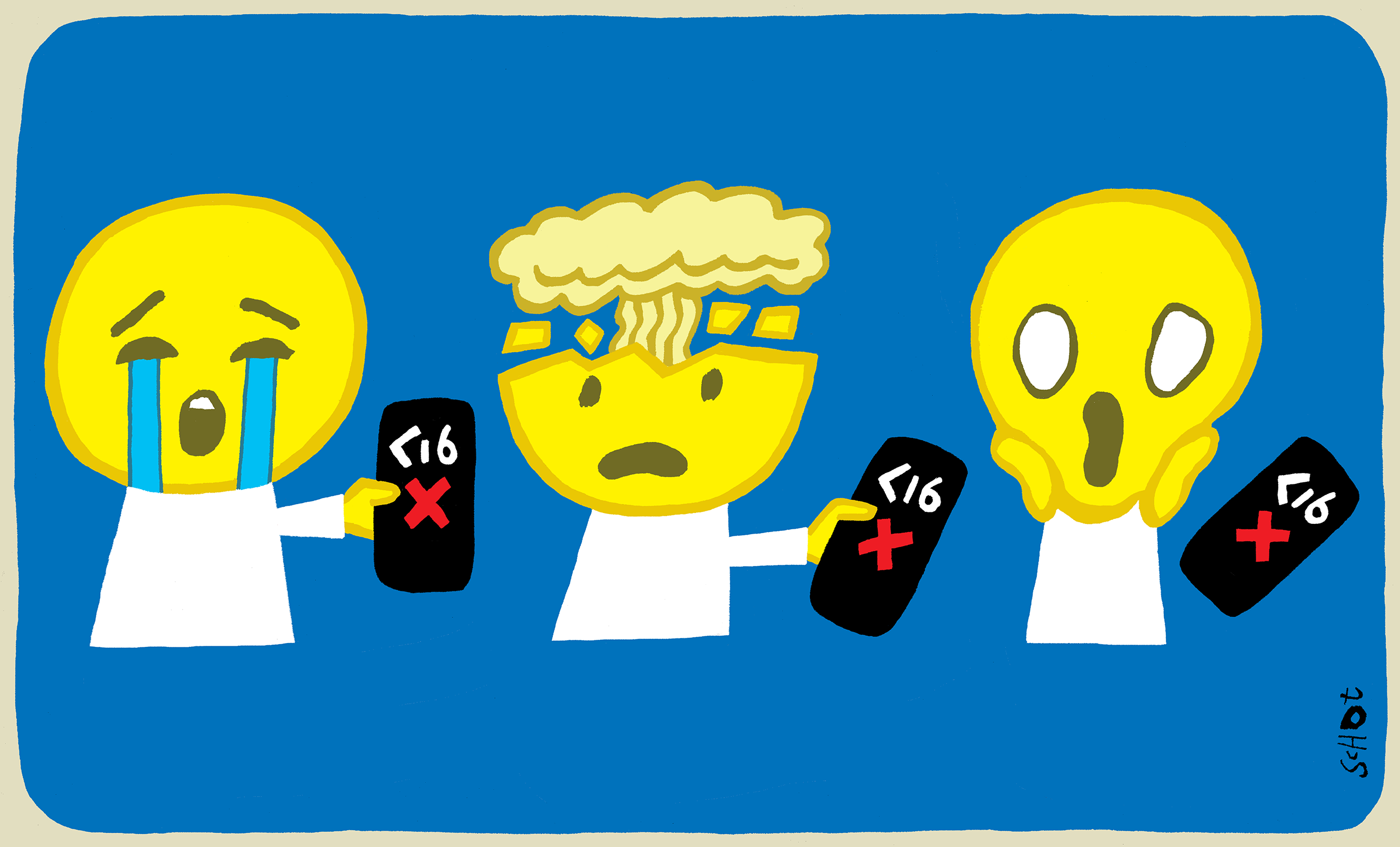

Why a social media ban for young people is not the solution

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-

-

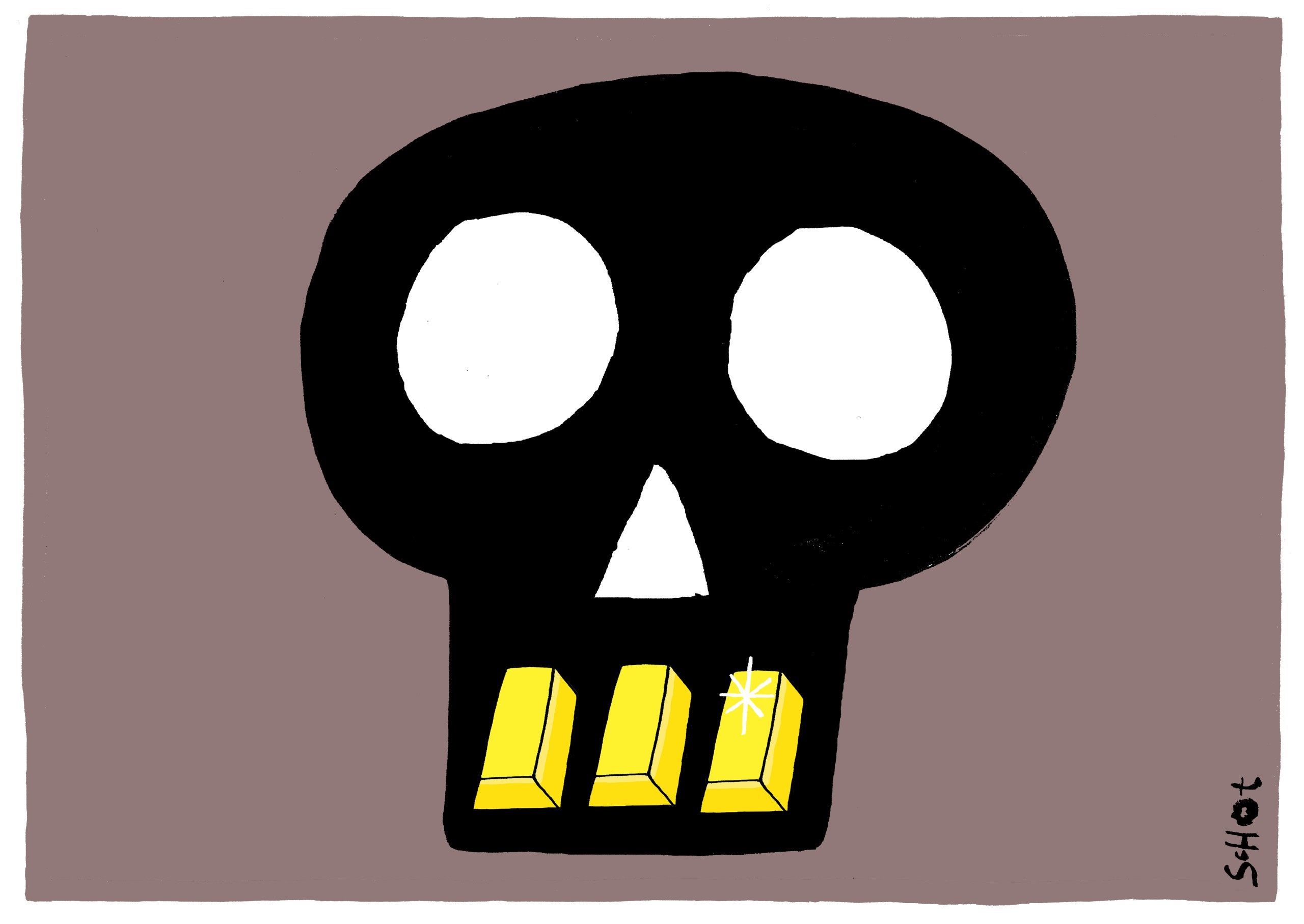

A self-funded war: how Sudan got trapped in a fatal deadlock

Gepubliceerd op:-

The Issue

-